By Celia Raney / New Mexico In Depth /

Going against federal guidance during the era of COVID-19, Albuquerque city personnel periodically roust homeless encampments. Waking inhabitants before sunrise, police deliver orders over a megaphone for men, women, sometimes families to move along in as quickly as 30 minutes.

In the frenzy of gathering themselves and belongings people have lost birth certificates and state identification cards as well as valuable personal mementoes, according to interviews reviewed by New Mexico In Depth conducted by a local service group that helps people living on Albuquerque’s streets.

Camps spring up regularly around Albuquerque, where every day hundreds live on the streets, particularly in downtown, in parks, under overpasses, tucked away in alleyways, in the doorways of businesses, and sometimes, on sidewalks.

Continuing a practice that was normal in pre-COVID-19 times, the city never lets them last for long, even while it’s unknown how many homeless people may have contracted the virus in Albuquerque so far.

One service organization, citing guidelines issued in March by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, wants the practice of breaking up camps to stop.

Street Safe New Mexico, a service organization helping homeless communities, women living on the streets and trafficking victims, says the regular sweeps inject more danger into already precarious lives because of the highly contagious COVID-19 virus.

For example, Executive Director Christine Barber said, one man was asked to leave his camp two days after being tested for COVID-19.

“He was potentially walking around the streets infecting people instead of being at his camp,” Barber said. “The policy is directly hurting people.”

The federal agency’s guidance on working with homeless populations during the pandemic, specifically camps, says “Clearing [homeless] encampments can cause people to disperse throughout the community and break connections with service providers, “increasing “the potential for infectious disease spread,” according to the guidelines.

“If individual housing options are not available, allow people who are living unsheltered or in encampments to remain where they are,” the CDC states.

“The whole goal [in containing] the virus has been to keep people in place so they’re not walking around infecting people,” Barber said.

The group sent a petition in May to the governor’s office asking medical experts to look into the issue and come up with a solution. And on Sunday, the group reiterated its call for the city to suspend camp clearances, asking instead that city officials help homeless people set up “covid-responsible camps” that house 5-10 people in tents pitched 12 feet apart, following the CDC guidance.

On Friday, a spokesperson for Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham told New Mexico In Depth in an email “the state recommends following CDC guidelines concerning homeless encampments and the ongoing pandemic. The request the petition makes is not one for which there is any existing structure – that would be an issue for the City of Albuquerque.”

The city’s deputy director of housing and homelessness, Lisa Huval, said it has always been city policy to clear camps, pandemic or not, because they pose other serious health risks.

As an example, a camp near Chico Road and Virginia Street was cleared in January, before the pandemic hit New Mexico, according to a report by Street Safe that relied on several people’s accounts.

Huval said the city would not be changing its policy, even with the recent spike in new COVID-19 cases in Bernalillo County.

“It starts with one tent and over a few days increases to three tents, within a few weeks, if the city were simply to allow that encampment to establish, could grow quite large, that presents other public health risks to that community,” Huval said. Those risks include improper disposal of needles, feces and urine on the ground, and other waste left in the area. While the CDC guidance is helpful, she said, “this is something that we really need to make decisions about at the local level.”

But clearing camps doesn’t mean needles and waste disappear, Barber said. The problem moves with the people.

“That’s not a new issue, that’s always been an issue and if you move the encampments, you’re still going to have feces and needles, it’s just going to be in different areas,” she said, adding that a simple solution would be to install public restrooms and syringe receptacles. “If anything it’s a reason to make people stay put.”

Clearing camps leads to other problems, Barber said. Service providers who were actively helping people in one location can lose contact with them, and people often lose their belongings when they can’t pack them quickly enough.

That can throw a wrench in the lives of people who are already dealing with great instability.

Without identification, people experiencing homelessness can’t get into many transitional housing or assistance programs.

![]() Every two years, the New Mexico Coalition to End Homelessness spends one night in Albuquerque counting people sleeping in emergency shelters, transitional housing, and outside or in unsheltered places. It’s referred to as a “point in time” count, and while it’s unlikely to capture the full number of people experiencing homelessness, it can help determine if the numbers are rising or falling.

Every two years, the New Mexico Coalition to End Homelessness spends one night in Albuquerque counting people sleeping in emergency shelters, transitional housing, and outside or in unsheltered places. It’s referred to as a “point in time” count, and while it’s unlikely to capture the full number of people experiencing homelessness, it can help determine if the numbers are rising or falling.

The last count, in 2019, found the largest population of homeless in Albuquerque since 2011 — 1,524 — and a nearly 300% increase in those who are classified as unsheltered — 567 — up from 144 in 2013, according to the report.

People are considered unsheltered when they aren’t in one of the six emergency shelters in the city or living in transitional housing. The number of people living in an emergency shelter has risen less than 19% since 2013.

The unsheltered either can’t or won’t seek refuge in a shelter due to a myriad of issues, including mental health problems. They could be living and sleeping in a park, on a bench, in cars, or even in the bosque or foothills.

The city’s clearance of encampments during COVID-19 includes those on private property.

Street Safe has given people permission to camp on their lot for a couple of days, usually while the center tries to get them into transitional housing, including two women whom Barber said were running from their trafficker and fearing for their lives.

“We had them in tents on our property waiting to get into rapid housing,” she said. “It was the only safe place to put them, we couldn’t afford a hotel and we thought just for a couple of nights we’ll put you in these tents where you’re safe, where you have hand sanitizer, where you’re social distancing where you have access to a bathroom, and then we’ll get you into your housing.”

Then, Barber said, the city asked them to leave.

“They came in and moved those women, we lost contact with a trafficking victim who was afraid of being killed by her trafficker because the city came onto private business property and moved people in the middle of an epidemic for no reason, it really doesn’t make any sense, it really doesn’t,” she said.

Private property owners can’t allow people to camp on their land unless that is what it was zoned for, Huval said.

“The city does not allow encampments on private property,” she said, adding that the planning department handles all camping issues on private property.

Encampments in Albuquerque at Coronado Park, a regular camping spot for unsheltered people. Image: Marjorie Childress.

According to Huval, city policy is to give 24 hours notice to residents of a camp before clearing it, unless there is a clear and present threat, for example a camp in an arroyo, or the people staying there are causing a disturbance. In that case, the city can ask the individual or group to leave immediately.

But reports collected by Street Safe from people removed and cleared from camps dispute the city’s stated policy. Sometimes people aren’t given more than 10 minutes to leave their camp, according to Street Safe interviews. And if they can’t pack up fast enough, their belongings are often tossed in a dump truck that accompanies the city’s team.

Several videos of camp clearing by police were posted to social media by Street Safe. They show people walking away from Coronado Park in Northwest Albuquerque and a line of city vehicles, including a dump truck, in the parking lot.

One person who was camping near Interstate 40 and Eubank told Street Safe all of their belongings were thrown away when the Albuquerque Police Department came to clear them. They reported that they were only given 30 minutes to move. They said police harassed and yelled at them over a loudspeaker at 2 a.m.

Another group told Street Safe they were only given a 30-minute warning from APD when they were moved from a park near Chico Road and Virginia Street, where they say they had been camping for several days under a tarp and were practicing social distancing with other campers. Someone lost a birth certificate and everything else they couldn’t pack quickly enough.

Out of 12 reports released to New Mexico In Depth, nine stated that the campers were given no prior notice to vacate the area. Nine people also reported their belongings were taken and or thrown away. One person said their birth certificate, social security card, and state ID were thrown away.

According to the reports, only one person thought the city handled the clearing professionally.

City organizes some supports for a population it keeps on the move

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the city created an outreach and testing plan for the homeless population that included motel vouchers for those awaiting test results or riding out the illness. In response to the closure of public places, including public restrooms, the city has set up 12 portable bathrooms in predesignated “high traffic” spots across the city.

All the portable bathrooms are equipped with hand sanitizer. Huval said there are no public hand washing or sanitation stations because the contractor the city works with had sold out, but the city is looking for an out of state supplier for handwashing stations.

Albuquerque Healthcare for the Homeless is partnering with the city to spread information pertinent to the homeless community Huval said, – how to stay safe, where to get help, when to get tested.

The city implemented a testing system at the Westside Emergency Housing Center, which is the only shelter operated by the city. The shelter has also implemented precautions to prepare for a possible outbreak, and has established isolation pods for people who are waiting for test results. All beds are now separated by six feet of space.

Huval said people are placed in hotel rooms to self isolate while waiting for test results. So far, she said, three people have tested positive at the westside shelter.

But the city doesn’t know how many homeless people in Albuquerque may have contracted COVID-19 to date.

“There is not a system in place to track testing, hospitalization and death rates for people experiencing homelessness specifically,” she said.“This is a system that would need to be in place by the state, as they are the entity in NM that oversees tracking and testing.”

As criticism of camps clearances mounted through the Street Safe petition in May, Albuquerque Mayor Tim Keller, a Democrat, said that because there are available shelter beds the city would continue clearing camps.

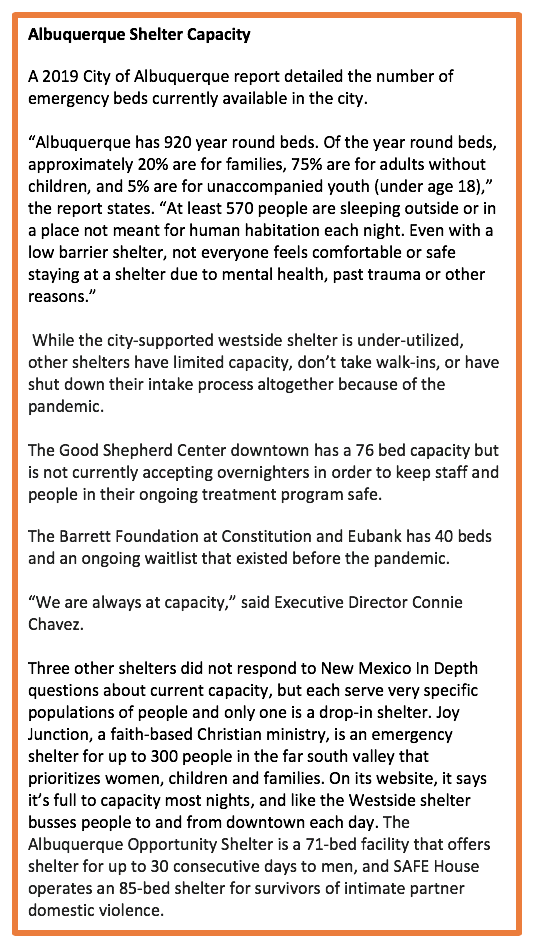

“We’re fortunate that in Albuquerque we have lots of good alternatives,” Keller said, in a live-streamed press conference, specifically mentioning the Westside shelter operated by the city. There are five emergency other shelters in and around Albuquerque.

But the unsheltered population doesn’t appear to have flocked to the city-supported shelter, choosing instead to remain on the street. Even though the Westside shelter holds 450 beds, Huval said there hasn’t been an increase in people coming to the shelter since the start of the pandemic.

In May, an average of 271 people stayed at the shelter nightly, Huval said. That means about 179 beds are left empty.

That the westside shelter doesn’t meet Albuquerque’s needs is well understood by the city. The shelter is 20 miles from downtown and the only way to get there is to be shuttled on a city bus which picks people up around the city in the afternoons and evenings. The same busses shuttle people back to town in the morning.

The city acknowledged as much in a 2019 report about efforts to bridge the gap between the homeless community and access to behavioral health services and long-term housing. “We have emergency shelters in Albuquerque, but capacity is limited, many are not open during the day and/or direct access is limited due to location,” the report states.

The city proposed last year to build a new, centrally located shelter that would house about 300 people nightly. Voters bought in, approving last fall $14 million for the project, named the Gateway Center. Initially, the plan was for the project to break ground in winter of 2020, but location availability issues and the impact of the pandemic forced the city to shift gears.

A new team composed of city, county and University of New Mexico officials is working to plan and open a multi-site center that will serve as a “low-barrier, 24/7, easy access” shelter providing services and transportation, according to an early May announcement.

“The Coronavirus pandemic has only made it more clear that this is a critical step for the community,” Keller said.

In the meantime, the city continues to break up homeless camps, keeping the hundreds of people living on its streets, on the move.

This story was originally published by New Mexico In Depth.

Celia Raney is a 2020 reporting fellow for New Mexico In Depth. A native New Mexican, Celia’s written, visual, and audio work has been published by the Albuquerque Journal, New Mexico News Port, KUNM Radio, Santa Fe Reporter, New Mexico Magazine, Talk Media News and the Daily Lobo. Contact her at celia.l.raney@gmail.com