By 1927 the mexican gray wolf had almost disappeared from the New Mexico wilderness. The once venerated wolf had been killed off as a result of trapping and hunting.

By 1950 all but few wolves were left in the United States, but in 1998 came the program that would bring them back.

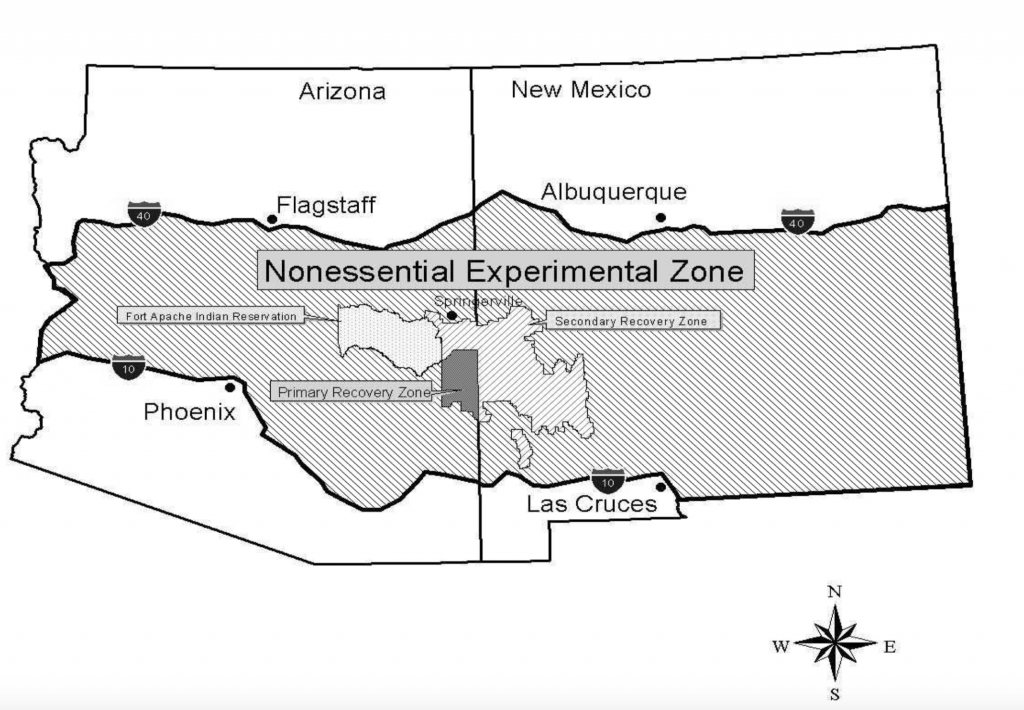

The mexican gray wolf reintroduction program has hit a new milestone this year with an all new population high of 131 wolves, in 32 different packs throughout Arizona and New Mexico. The population is split almost evenly between the states. It has also recently been named a subspecies of the gray wolf.

While the gray wolf has been removed from the endangered species list, the mexican grey wolf remains. Still, the program, a responsibility of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, has made a landmark achievement, although conservationists feel that it is not enough and ranchers are concerned that the population growth may become too much.

With the continually growing population, ranchers are feeling the pressure on their livestock. There have been 20 recorded depredation of livestock between the beginning of January and the end of February. The majority of the livestock lost were calves.

“If the ranchers aren’t out there all the time, then they lose livestock. Wolves kill indiscriminately,” said Doug Crespin, a rancher and hunter.

There are recompensation programs set up in both Arizona and New Mexico to help ranchers affected by the wolf population, but Crespin feels it is not only the ranching industry that is affected. The game industry has also been affected by the growing wolf population as well.

“I think it’s wrong to have an overpopulation of wolves where it is detrimental to other wildlife and livestock,” Crespin said. “Way back when all the wolves were here and there were plenty of wolves, there wasn’t all the livestock that there really is now. There wasn’t the game industry, they’re eating the elk up.”

Judy Calman, the staff attorney from NewMexico Wild, said her organization helps encourage the public to stand up for wolves by calling representatives and The Fish and Wildlife service. NewMexico Wild has been part of the wolf recovery process since the beginning in 1998.

Calman says for wolves and ranchers to coexist it requires some mutual respect and some willingness by the ranchers to alter the way they ranch.

According to the Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, produced by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the lobo will be considered to be removed as a protected species when the average of an eight year population reaches 320. Currently the eight year average is 91.

Calman said when making the new rules a panel was put together containing experts and scientists.

“The agencies are supposed to use best available science when they make the decision,” Calman said. “The panel decided that for wolves to be recovered they needed 750 wolves in three different populations connected by corridors and each population needed to be at least 250 wolves apiece. That would be the number needed to achieve recovery where the wolf wouldn’t need endangered species protections anymore.”

Currently NewMexico Wild have two lawsuits against Fish and Wildlife Service. Fish and Wildlife service implemented two new rules to help with the control and governing the wolves.

“We felt (we) did way too little for wolves,” Calman said

In 2015, NewMexico Wild was involved in a lawsuit where they claimed the DOJ failed to press charges on individuals involved in the killings of wolves. They eventually lost this case in federal court.

Calman said with the lawsuits going they got a good ruling in district court adding that the plan needs to be redone because Fish and Wildlife Service did not listen to best available science.

The court gave Fish and Wildlife Service twenty five months to make a new rule.

“I don’t say the introduction is a mistake as long as it is managed,” Crespin said. “Everything in moderation, if they can balance the wolves out with the other wildlife and the livestock.”

Calman said wolves are important because the Gila National Forest is one of the nations first wildenrenesses.

“For us it’s about making America’s first wilderness be the way it should be,” said Calman