By Natanya Friedheim, Anna Heqimi, Karla Perez, Lauren Cohen, Allison Muzzy and Brooke Holzhauer

Last year, Cing Cing Hlamyo and four other Burmese families in Missouri pooled their money to join Welcome Corps. Launched by President Joe Biden’s administration in 2023, Welcome Corps allowed people in the United States to sponsor refugees.

“When it opened, all the Burmese, they were so excited,” she said.

The group put money in a bank account for the expected refugee. Then in January, the program abruptly shut down. “We’re just waiting. That’s all we can do now,” Hlamyo said.

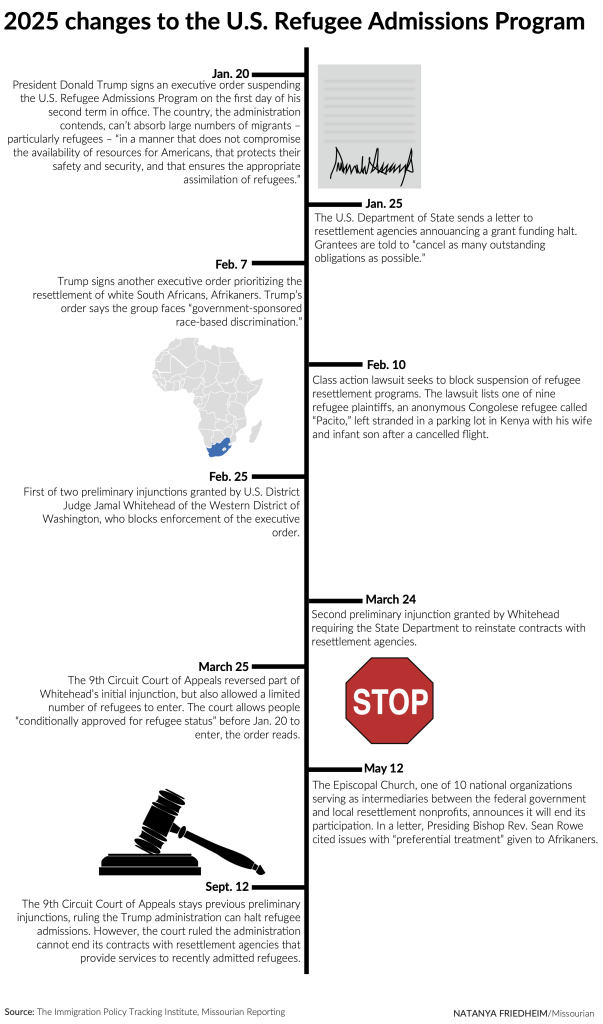

Welcome Corps is just one facet of refugee resettlement in America that President Donald Trump changed dramatically when he began his second term Jan. 20. As part of a larger withdrawal from international humanitarian aid, Trump signed an executive order halting the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program. The State Department also ended funding to local resettlement nonprofits, though a lawsuit later restored some of that money.

Across the country, nonprofits have closed their refugee resettlement programs or are looking for new funding sources, with many waiting to see if the pipeline will reopen.

Following the federal Refugee Act of 1980, the U.S. built a formidable bureaucracy to resettle people who face persecution abroad. Federal agencies vet applicants, many of whom live in refugee camps scattered across the globe. Once approved, a network of nonprofits uses federal funds to help newly arrived refugees get on their feet.

Trump’s re-election last year reflects a growing animosity among Western countries toward globalization. The president has denounced international institutions like the United Nations, which partners with the U.S. and other countries to resettle refugees.

This year’s federal budget bill made refugees without a green card ineligible for benefits including the federal food assistance program. It also affected their eligibility for full Medicaid benefits and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Bonnie Gay of Princeton Alliance Church in New Jersey has seen the impact of refugees whose arrivals have been blocked.

“Every story is one of trauma and loss,” said Gay, who leads the church’s Alliance for Refugees. “They come seeking safety and a fresh start where they can put down roots in a place of welcome and peace.”

No money for the American Dream

Some nonprofits ended their refugee resettlement programs entirely.

Connecticut’s flagship resettlement agency, Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services, lost $4 million in federal funding. As a result, the agency closed offices in Hartford and New Haven.

War drove a University of Connecticut student to flee from Baghdad, Iraq with her family. IRIS supplied the refugee family with food, a studio apartment and legal counsel upon their arrival.

The second-year student, who requested anonymity, said she fears ongoing deportations, but feels supported in her new hometown of New Haven and within the community she built at the University of Connecticut. A university sorority, Mu Sigma Upsilon, held a donation drive for IRIS in late September. “I am grateful for the education and opportunities America has given me,” she said.

Some organizations diversified their income streams to continue offering services to refugees years after their arrival.

Trump’s executive order contends the U.S. can’t absorb large numbers of immigrants — particularly refugees — “in a manner that does not compromise the availability of resources for Americans, that protects their safety and security and that ensures the appropriate assimilation of refugees.”

Hillary Baez, the refugee services assistant program manager of Catholic Charities of Southwest Kansas saw the changes coming. “Our organization basically took that as an initiative to try and find other sources of funding to ask for more donations from our donors,” she said.

The organization opened a thrift store and has plans to open three more “as just another way for us to keep ourselves running,” Baez said.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, one of 10 national organizations that partnered with the federal government to distribute resettlement funds, announced in April it would end its partnership. Two Catholic Charities affiliates — Northeast Kansas and Central and Northern Missouri — were among those that ended their local refugee resettlement programs.

When Catholic Charities of Central and Northern Missouri in Jefferson City dissolved its refugee services in March, three of its employees moved to City of Refuge in nearby Columbia.

Refugees that the organization helped were directed to City of Refuge and Della Lamb Community Services, another nonprofit, in Kansas City.

Visitors touring City of Refuge on a recent morning saw civics classes where refugees prepared for the citizenship test with questions like: If the president and vice president are unable to serve, who takes over? Touring guests knew the answer (the speaker of the House) but couldn’t recall the current speaker’s name.

“Mike Johnson,” a man seated in the class said under his breath.

City of Refuge has continued to provide citizenship classes even as the Trump administration cut federal funding for similar services to other organizations. Up to $500,000 in federal funding for the nonprofit will expire in October 2026, and it’s not clear what federal funding will be available after. Because of that, the City of Refuge is looking to diversify its financial support.

Hlyamo is one example of what those who have benefited from City of Refuge have accomplished.

By many accounts, Hlamyo, one of more than 3.6 million refugees who entered the U.S. in the last 50 years, achieved the American dream.

She was five months pregnant and owned one jacket when she and her husband arrived, their 18-month-old daughter in tow, in November 2009 to face their first Midwest winter.

Growing up in Myanmar was fraught. Hlamyo watched soldiers beat her father – the military wanted use of his truck, but its engine was broken. They forced her family into unpaid labor.

Hlamyo now enjoys the fruits of her hard work in America. The mother of four owns an Asian grocery store, one of the few places in mid-Missouri where shoppers can find frozen octopus, bitter melon, jackfruit chips and South Asian specialties. Her eldest daughter is applying for college.

No help for 2025 arrivals

A court order required the Trump administration to admit refugees who had approved applications and confirmed travel plans by Jan. 20.

An attorney with the International Refugee Assistance Project, which sued on behalf of resettlement agencies and refugees, said 70-100 people entered the country as a result of the injunction.

Baez said Catholic Charities of Southwest Kansas welcomed three refugees from Eritrea, in East Africa, after Jan. 20 because the group already had flights to the US.

However, federal funding cuts meant they couldn’t get assistance previously available to recent arrivals. Catholic Charities of Southwest Kansas could still provide services such as employment and English assistance.

Tatjana Bozhinovski, resettlement program director at Ethiopian Tewahedo Social Services in Columbus, Ohio, said her organization was affected by the executive order on day one.

A single mother with four children arrived on Jan. 17, and three days later, Bozhinovski had to tell the family that the nonprofit could no longer help them find housing, enroll kids in school or find jobs.

“You can’t possibly do that if you have a heart and if you have a soul,” Bozhinovski said. Ethiopian Tewahedo Social Services lost 75% of its staff, many of them refugees, as a result of the federal money freeze.

Some people with confirmed travel plans were still unable to enter following the executive order.

Tyler Reeve of Community Refugee & Immigration Services in Columbus helped some members of a family arrive on Jan. 17. The rest were unable to enter, even though they were approved as refugees and had purchased plane tickets for February. The family is separated indefinitely. Layoffs left the organization with no full-time resettlement staff.

Jewish Family Services in Columbus lost more than $2 million.

Tariq Mohamed, the nonprofit’s senior director of refugee services, welcomed a teenage boy and girl right before Jan. 20, expecting their parents and the rest of their siblings to arrive in February. The family doesn’t know when they will see each other again.

The nonprofit has been able to continue some of its other programs, including helping refugees already in the U.S. find employment, register their kids for school and get vaccines, as federal funding still exists for those.

From Oct. 1 to Jan. 20, Jewish Family Services resettled 184 people, doing an entire year’s worth of work in three months before the order passed, in anticipation of Trump’s actions.

Under Biden’s administration, refugee admissions for the fiscal year 2024, which ended last October, reached 100,034, the highest annual total since 1995.

“It was a big, big ramp up over the last few years,” said Paul Costigan, Missouri’s state refugee coordinator.

Few new arrivals

A spokesperson for the State Department, which oversees the refugee resettlement program, did not provide numbers when asked how many refugees have entered the country since Trump took office this year.

The Trump administration is considering a new annual ceiling of 7,500 for fiscal year 2026, which started Oct. 1, according to reporting by The New York Times.

The Missouri Office of Refugee Administration used to get monthly reports from the State Department on how many refugees to expect and how many ultimately arrived. Those reports ceased in January, said Costigan.

Princeton Alliance Church in Plainsboro, New Jersey, established refugee services in 2023 with approval from the State Department. It welcomed 135 immigrants before the executive order. The church had expected another 100 people this year, but only 26 made it in the waning days of the Biden administration.

Two people scheduled to arrive in late January had their tickets canceled, said Gay, the executive director of the church’s Alliance for Refugees.

Under previous administrations, Jewish Vocational Service was Kansas City’s largest refugee resettlement agency. In fiscal years 2023 and 2024, the agency resettled 409 and 630 refugees, respectively. Following Jan. 20, the agency has served only 60 new arrivals.

Reese Taw’s work at Jewish Vocational Service is personal. A member of Karen, an ethnic minority group in Myanmar, Taw and his family arrived in the U.S. as refugees when he was nine. A resettlement agency helped his family adjust to life in America.

“I get to help the same people that were in my position a while ago because I can relate to the frustration,” Taw said. “Just being able to serve the community, as a whole, it’s fulfilling to me.”

Taw was one of 12 employees the nonprofit laid off in March. He was rehired, but the organization is grappling with funding loss. “We’ll try to survive as long as we can, but we’ll see what happens,” Taw said.

States assume larger role

Looking to the future, Costigan of the Missouri refugee office predicts an overhauled refugee resettlement program where states have more control. Some states are already putting their own funding behind programs cut by the federal government.

New Jersey Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy created the state’s Office of New Americans in 2019, amid Trump’s first-term immigration crackdown. New Jersey had at least $1 million cut since Trump returned to office in January, state budget documents show. Murphy pledged to double the state’s support for its initiatives.

New Jersey lawmakers this year boosted the state-run Refugee Resettlement Program to $29.5 million, six times greater than the previous year. The money goes to seven nonprofits, which offer refugees cash, case management, job assistance, health expenses and other aid.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont signed a bill in March allocating $2.8 million to programs targeted by the Trump administration. IRIS, New Haven’s flagship resettlement agency, and another organization received a total of approximately $500,000.

People involved in refugee resettlement say the commitment from local communities has remained steady.

Jewish Vocational Service saw an outpouring of support from the Kansas City community after losing its federal funding for refugee services.

At a September meeting in Joplin, a city of 53,000 in southwest Missouri, people from the fire department, community college and city government showed up to coordinate assistance for recently arrived refugees.

“The community commitment is there,” Costigan said.

This article was produced through the Statehouse Reporting Project, a collaborative effort by collegiate journalism programs across the country.

The Statehouse Reporting Project is a collaborative project of university-led newsrooms across the country. Facilitated by the Center for Community News at the University of Vermont and the University of Missouri School of Journalism, the collaboration illuminates emerging trends in policy and politics on critical issues in public life.