Communities nationwide are trying to crack the same nut: how to narrow the achievement gap between rich and poor kids. Pensacola, Fla., became one of the country’s first cities to dub itself an “Early Learning City.” With leadership from the business community, it linked up with the University of Chicago’s Thirty Million Words project to educate new parents on how to build their child’s brain — a project that could hold lessons for New Mexico.

PENSACOLA, Fla. — Water shimmers around every curve in the road: an emerald beach, a blue bayou, a choppy bay. Vines of lilac grow like weeds. The air is thick with humidity.

To the eye, this coastal community on the Florida Panhandle looks nothing like New Mexico. But on paper – when it comes to child well-being – they could be first cousins.

Much like New Mexico, a third of Pensacola’s children aren’t kindergarten-ready. More than a fifth of its high schoolers fail to graduate. Thirty-eight percent of its households are headed by a single parent. More than half of births are covered by Medicaid, while more than a third of pregnant women lack adequate prenatal care.

Led by an invigorated business community, Pensacola has taken up early childhood as its cause, dubbing itself an “Early Learning City” and rallying around a program to universally educate all new moms – 5,000 each year — on the importance of building their children’s brains from infancy.

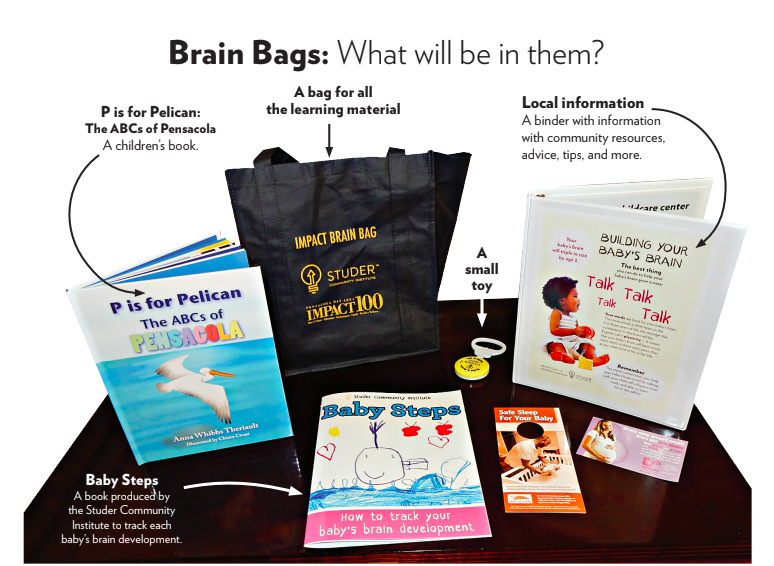

Last year, Pensacola’s three major birthing hospitals introduced a campaign centered around a gift to new parents: the “Brain Bag.” It’s literally a bag full of resources on brain development, based on a research program at the University of Chicago called Thirty Million Words.

The bag is a door opener with new parents, said Catherine Kovaleski, a labor and delivery nurse at Pensacola’s Baptist Hospital — a way to start a conversation to dispel myths and share the latest brain science.

“We laugh about it when we bring it up: ‘You just had a baby! Let’s talk about getting them ready for kindergarten!’” she said.

According to oft-cited research, children from privileged families hear, on average, 30 million or more words by the end of age 3 than children from low-income families — setting higher-income kids on a path for greater success in school.

To close the achievement gap, the theory goes, a community must close the language gap. The Brain Bags are the brainchild of a Pensacola nonprofit called the Studer Community Institute, founded by health care guru Quint Studer, who made a fortune in hospital consulting before setting his sights on improving Pensacola.

Each bag contains a binder with a bib and rattle reminding parents to “talk, talk, talk.” There is a picture book, “P is for Pelican,” and a workbook with developmental milestones for parents. The bags, free to parents, cost $25 apiece to produce and are assembled by adults with developmental disabilities.

The $108,000 project is privately funded by a network of women donors and embraced by the business community; its outcomes will be tracked once babies born in the past year hit kindergarten.

“In health care, the majority of money is spent on symptoms — the same thing in education,” said Studer, who has led the “Early Learning City” effort.

“In Florida, we tried to get some money for [age] 0 to 5, but it all went to ‘K’ and above because that is who has got all the lobbying power: the public school system and the universities,” he said. “But the reality is, if 85 percent of the brain is developed by age 3, that is where we need to be focused. What we’re really trying to do is treat the cause.”

Sidestepping government

Across the country communities are experimenting with early childhood programs. New Mexico increased its state investment in early childhood programs to more than $300 million in fiscal 2018. Child advocates, citing that same brain science, have demanded an additional $140 million annually from the Land Grant Permanent Fund for early childhood programs. Their proposals have met failure in the state legislature seven years running.

Pensacola has given up waiting on the state and federal governments.

Business leaders a year ago were persuaded by emerging brain science showing how about 85 percent of a child’s brain — including its 100 billion neurons — is hard-wired by the end of age 3. Language is what builds these brain connections and enhances a child’s capacity to learn; the most important component for building strong brains is parent talk.

The Brain Bags emerged as one potential solution, as well as an effective fundraising tool for the philanthropic and private sectors.

Pensacola’s approach follows a national trend in which business and local leaders are increasingly assuming the mantle of responsibility to solve all kinds of entrenched problems. They’re taking the lead, not just for the good of the community, but for the twin purposes of workforce and economic development.

Take the Florida farmworkers who dramatically improved their work conditions without new government regulation or legislation by creating a “Fair Food Program” in conjunction with farmers and retail food companies. The program ensures humane wages and working conditions for the workers who pick fruits and vegetables on participating farms.

Or the now decade-old StriveTogether partnership of 300 business and community groups in Cincinnati that created a framework for disparate organizations to work toward specific educational goals: The project, which has since gone national, has boosted kindergarten readiness and high school graduation rates in communities around the country.

“We need to look at new places for new solutions” to entrenched, generational problems that government clearly hasn’t solved, says Susan Marquis, dean of the Frederick S. Pardee RAND Graduate School. “Governments still matter but increasingly nonprofits, NGOs and even the private sector — they are not only influencing policy but making and implementing policy.”

The talk connection

It began as a reporting project. The Studer Community Institute hired former journalists to write a report on the causes and impact of poverty in Pensacola. Their research led them through a maze of crushing statistics and sociological theories — until they found Dana Suskind at the University of Chicago.

Suskind is a pediatric cochlear implant surgeon who implants hearing aids in hearing-impaired babies and toddlers. It’s a rewarding profession filled with emotional moments. But from the very beginning of her surgical practice in 2005, Suskind encountered a frustration: While her pediatric patients from middle- and upper-income families rapidly caught up in language acquisition and speech, the children of low-income families did not. She set out to discover why.

That is when she discovered the seminal work of psychologists Betty Hart and Todd Risley, who in the 1980s were the first to identify the language gap.

Their research followed 42 families in Kansas City, Kansas, over three years, observing baby development from 9 months to nearly 4 years old. Based on characteristics like parental occupation, maternal education and income, they divided the families into three groups: high, middle and low socioeconomic status families.

After recording and analyzing everything “done by the children, to them and around them” for an hour per family each month over the course of three years, Hart and Risley found remarkable similarities in parenting approaches and goals. Parents all “socialized their children to a common cultural standard,” and the kids all learned to talk.

But the difference in the language they heard – the quality and quantity of words – was stunning.

On average, in the course of one hour, the highest socioeconomic status children heard 2,000 words; the children of low-income families heard only 600. The highest-income parents responded to their kids an average of 250 times an hour; the lowest-income parents about 50 times. The gap by 4 years old? Thirty million words.

“But the most significant and most concerning difference? Verbal approval,” Suskind wrote in her book Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain (Dutton, 2015). “Children in the highest socioeconomic status heard about 40 expressions of verbal approval per hour. Children in welfare homes, about four.”

Some scholars have questioned Hart and Risley’s findings, discrediting the small sample size and challenging the idea that altering language at home could help children overcome extreme social inequality.

But Suskind focused on a subtle point in her study: The essential factor that determined a child’s future learning trajectory wasn’t socioeconomic status. It was the quality — and positive nature – of the language spoken. Money didn’t matter; words did.

“Children in homes in which there was a lot of parent talk, no matter the educational or economic status of that home, did better,” Suskind wrote. “It was as simple as that.”

In Chicago, the Thirty Million Words project today teaches new parents to “tune in, take turns and talk more” — the three T’s for paying attention to a child’s cues, taking conversational turns and talking more. Suskind envisions the program being implemented in prenatal care, at birthing hospitals, in pediatric clinics and home visits around the city.

“What we aspire to is a population-level shift where all parents and caregivers understand the power of language to build their child’s brains and know how to implement it,” she told Searchlight New Mexico. “We want it to be in the groundwater.”

Spreading the message

In Pensacola, the hospitals were an obvious place to start, since virtually every birth in the city occurs in one of the three facilities. Baptist Hospital, Sacred Heart Hospital and West Florida Hospital have been cutthroat competitors in nearly every medical specialty. But when the CEOs were individually approached, each agreed to collaborate.

Baptist Chief Executive Mark Faulkner said, “I personally spoke to the CEO at West Florida and said, ‘Y’all need to do this.’ For us it was a no brainer, no pun intended. If there is evidence that says this is good, it is right in line with our mission.”

It will take at least five years to see whether the project, which began in April 2017, has any impact on kindergarten readiness. But moms who have received the Brain Bags say the information has been enlightening.

Kristina Broxterman, a 30-year-old hair stylist, gave birth to baby Lincoln Josiah in January at Baptist.

“It was actually really encouraging,” she said. “For me, I didn’t understand the amount of brain development before three years.”

The Studer Community Institute acknowledges that it will take more than a bag and a conversation in the delivery room to change decades of inequality. It plans to reinforce the “tune in, take turns and talk more” message to parents wherever it will have the most impact.

The next step will be to present new mothers with a video on brain development, part of the University of Chicago’s research. Studer also plans to press area pediatricians to reiterate the Thirty Million Words message at well-child visits.

Reggie Dogan, a former journalist and researcher who helped shape the Institute’s mission, calls the outreach effort “a day-to-day struggle.”

Parents, especially mothers in poverty, “may increase their reading today, but will they continue three years, five years, down the road?” he asked. “Or will this child fall by the wayside just like the parent did? That is what scares me.”

Also on this topic:

Looking home for solutions: Journalist sees her Florida hometown boosted by program for kids

Birth of the ‘brain bag’: A conversation with Quint Studer