The Carlsbad region was poised to send $3 billion to New Mexico coffers, thanks to one of the biggest oil booms in history. Then came COVID.

By Rachel Mabe and Ed Williams | Photography by Don J. Usner | Searchlight NM

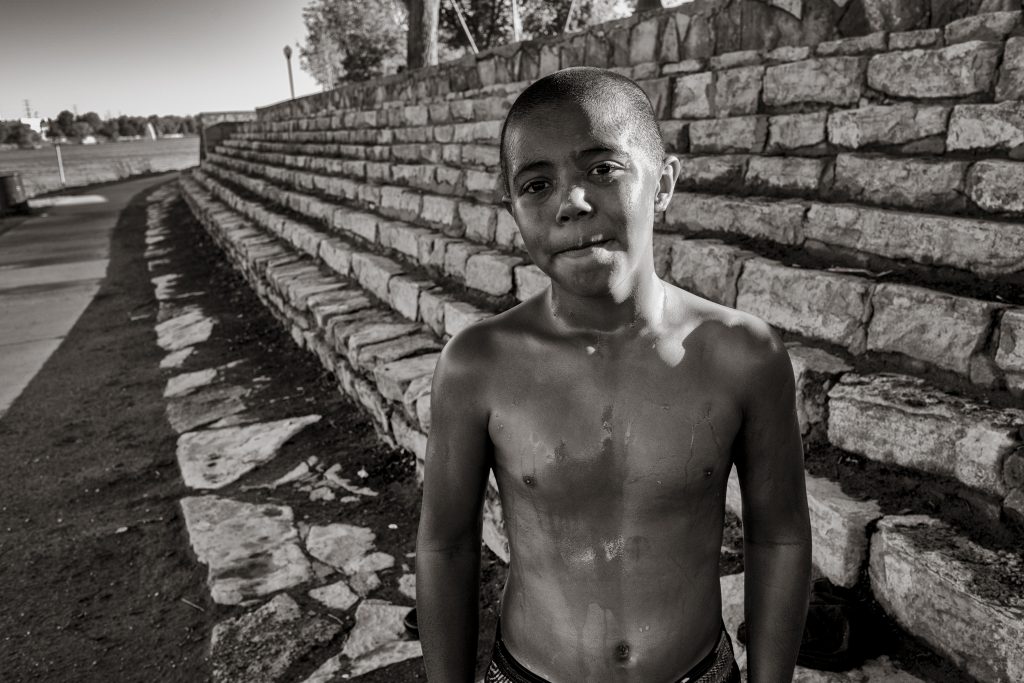

CARLSBAD, N.M. — On a Thursday in late May, Michael Trujillo sat in the slightly softened evening light and watched his three children play in the water at Lake Carlsbad Beach Park, an unexpected patch of blue in the Chihuahuan desert. With his pit bull puppy at his feet, Trujillo passed slices of pizza from a stack of three Little Caesars boxes to two men in camp chairs.

All three are oilfield workers, Carlsbad natives and, unlike thousands of others in the industry, all are still employed. But that hasn’t relieved their anger at the New Mexico governor and her coronavirus shutdown orders.

“She needs to open the place up and let us do what we need to do,” the 36-year-old Trujillo said.

Like a lot of people in town, Trujillo wishes Carlsbad was in Texas.

In that state, just 40 miles to the south, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott didn’t order a COVID-19 lockdown until April 2 and allowed businesses to start reopening by May 1. By comparison, Democratic Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham issued some of the nation’s strictest stay-at-home orders and didn’t ease them until June. That didn’t sit right with Carlsbad locals.

“It just hasn’t hit us really; we don’t have many cases,” said Valentine Bustos, Trujillo’s cousin.

None of the men wore a face mask. Neither did the scores of other people in the park. “We should have been able to reopen weeks ago,” Bustos said.

Welcome to Carlsbad, one of the most defiant and incongruous places in New Mexico. It is a Republican stronghold in a blue state — a speck in the desert with outsized clout. Nothing about it suggests vast wealth. But it sits atop one of the most productive oil fields in the world, a fabulously rich basin that makes the Carlsbad region the most powerful in the state, able to boost New Mexico or betray it. Even a small economic hit to Carlsbad can mean a gut punch to the rest of the state.

“We’re dependent on an industry that we have no control over,” said State Land Commissioner Stephanie Garcia Richard, who oversees oil and gas leases on state-owned land. New Mexico has over-relied on the Permian to fund state government for far too long, she said, her voice rising in frustration. “This industry is so volatile!”

The arrival of the coronavirus made this painfully evident. In February, after a year of record-breaking output in the Permian Basin, an ebullient New Mexico legislature believed it had an unprecedented $3.1 billion in oil and gas revenues. The state was preparing to spend the windfall on an ambitious “moonshot for education” and early childhood programs — long-needed initiatives that Lujan Grisham hoped would pull New Mexico out of its unenviable position as America’s worst state for child well-being.

By March, the price of a barrel of crude was plummeting. By April, the price of oil nosedived below zero for the first time in history. New Mexico’s windfall vanished, leaving the state with a $2 billion budget shortfall.

Lawmakers watched in horror as the COVID-19 pandemic thrust the world’s oil markets into chaos. Oil and gas businesses in other states laid off more than 100,000 workers, tried to calm investors and, in some cases, went bankrupt.

State Sen. John Arthur Smith, the outgoing conservative Democrat who for 31 years held a tight leash over New Mexico’s budget, had one last opportunity for an I-told-you-so.

“The ‘moonshot’ was, quite frankly, a fiasco, given a revenue stream that relies on oil and gas,” Smith said.

In keeping with its contrary nature, Carlsbad has weathered the crisis relatively unscathed.

Carlsbad Mayor Dale Janway gave a running commentary on the city’s health while giving a recent tour through town.

“Oil prices are trending, and we’re seeing more traffic,” he said, motioning out the window.

It was May, and New Mexicans were supposed to be sheltering in place and wearing masks in public, but Carlsbad was full of bare faces.

Janway wore a mask until he got into the pickup truck with reporters and immediately took it off. “We’re also still seeing a lot of growth and development around town,” he said.

There have been oil worker layoffs, but most have fallen on transient workers from out of state, according to New Mexico’s petroleum trade association. Locals who lost their jobs quickly found work in the city’s restaurants and shops — a fact underscored by Eddy County’s May unemployment rate of 5.6 percent, one of the lowest in New Mexico and about half the rate in Texas oil towns.

So why do Carlsbad residents wish they lived in the Lone Star state?

Trujillo, like a lot of people in town, is riled about New Mexico’s reactions to the virus. In keeping with their conservative political bent, many residents believe that COVID-19 has been overblown and that Texas, with its relaxed public health restrictions and swift reopening, is taking the right course. The recent surge of novel coronavirus cases in Texas — an increase traced directly to the early reopening — has done little to dampen their admiration.

In the past two weeks, Texas has become a pandemic epicenter, reporting more than 6,000 cases in a single day, triple the number seen in previous weeks. Cases in Carlsbad and the wider Eddy County area have also been spiking, likely due to travel to and from Texas, health officials said. Between June 3 and June 29, the number of confirmed cases in Eddy County more than tripled, going from 23 to 78. One person has died.

Dale Balzano, a retired teacher and coach who in 2007 turned an old bank into a boutique hotel and restaurant called The Trinity, said that compared to Texas, New Mexico is a “hard place to do business.” The governor was picking winners and losers: Major corporations and box stores like Lowe’s were allowed to stay open, he said, while the little stores were forced to close. Balzano said he comes from a long line of democrats and labor union organizers. “But this governor scares the heck out of me.”

Lujan Grisham’s aggressive public health response has scored her significant political points on the national stage and is among the reasons she is on the vice presidential shortlist for presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden. But it has earned her few brownie points in Carlsbad and Eddy County. In early May, county commissioners drove that point home by voting to sue the governor, claiming that her emergency orders infringed on civil liberties and free trade.

And after Lujan Grisham in May ordered masks to be worn in public to stem the spread of coronavirus, Eddy County Sheriff Mark Cage publicly refused to enforce it. “This is America,” Cage told the Carlsbad Current-Argus. The sheriff and his deputies would not be wearing masks, Cage said, and if that made anyone nervous, “then you have the right to move away from me.”

New Mexico’s big oil gamble

When Lujan Grisham coasted to office in 2018, she did so on a platform of big plans. In her 2020 budget, crafted with support from the Democratic-controlled legislature, she dramatically expanded child-care assistance, provided free preschool and two-year college, boosted health care and public safety budgets, and gave public school teachers substantial pay raises. The plan also included an overhaul of public education, which advocates hoped would close the state’s cavernous achievement gap for Native Americans, low-income children, English-language learners and special education students.

For decades, lawmakers had said they didn’t have enough revenues to tackle the state’s desperate problems — child poverty, substance abuse, failing schools. And suddenly they did. The Permian Basin was generating fortunes for state coffers through oil and gas royalty payments. When in February the legislature passed a $7.6 billion budget — the biggest in state history — it did so with confidence that the Permian would continue to be a cash cow for a long time to come.

For many in Carlsbad, this fed into a familiar grievance: Big spenders in Santa Fe were taking money from the southeast and funneling it away, never to be seen again by locals. In fact, Carlsbad has always been a place where natural resources have propped up both the state and the local economy.

Potash, caves and nukes

More than 100 years ago, Anglo settlers dammed the Pecos River and diverted the water into the surrounding plains, creating an oasis of green farmland in the mostly parched desert. In 1925, a surveyor looking for oil instead found the nation’s first deposit of potash, a mined salt used in everything from fertilizer and detergents to pharmaceuticals and animal feed. Carlsbad became one of the potash capitals of the world.

When the potash industry declined, the city found another subterranean resource to take its place: In 1999 it became home to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, where nuclear waste is deposited in salt formations deep underground. The plant, which shut down from 2014 to 2017 due to a radioactive leak, has resumed operations and last year received its 12,500th radioactive shipment.

Today, Carlsbad is largely known for two things: the Carlsbad Caverns, one of the most spectacular caves in North America, and the Permian Basin, the 75,000-square-mile formation that extends across west Texas and southeast New Mexico.

Prospectors first began pumping oil from the basin in the 1920s. And for decades, fuel production there was steady, if not dramatic. All that changed in the 2000s, when a revolution in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling technologies made it economical to extract oil and gas deposits that had previously been too costly to reach. The results were staggering: Between 2009 and 2019, New Mexico’s oil production increased 400 percent, making the state the third-largest oil producer in the nation. The Permian Basin was now generating more oil than most members of OPEC, providing more than 30 percent of all U.S. oil production, studies showed.

In many ways, the boom was more than Carlsbad could handle.

“I mean, it just ridiculously overtaxed the infrastructure,” said Jim Winchester, executive director of the Independent Petroleum Association of New Mexico. Carlsbad’s roads are pockmarked with potholes and woefully inadequate to handle the heavy truck traffic that rumbled through day and night, bumper to bumper, during the boom. One road, U.S. Highway 285, earned the moniker “Death Highway” for its sky-high rate of traffic fatalities, many of them caused by oil industry rigs.

“Using that road is like dodging bullets every day,” said Trujillo, the local oil worker.

The former farming town drew thousands of oil and gas workers from around the country, who made an average of $98,000 a year and lived in local RV parks and modular corporate “man camps.” In recent years the city ballooned to more than 52,000 residents, according to Janway. Housing costs in Carlsbad increased, as did oil spills, air pollution and other environmental impacts.

“The Permian boom is a carbon bomb,” said Tom Singer, senior policy advisor at the Western Environmental Law Center. Since COVID-19 arrived, oil production has been cut in half. “But even at 50 percent throttle, New Mexico’s addiction to oil revenue is completely unsustainable for those of us who depend on the planet,” he said.

The Permian last year had the worst oil- and gas-related air pollution in the country, according to a 2020 study published in the journal Science Advances. The report concluded that the Permian leaks some 2.7 million metric tons of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere every year — the highest rate ever measured from a U.S. oil- and gas- producing region.

“Raining down chemicals”

In Carlsbad, the environmental dangers came into unusually vivid relief earlier this year when a pipeline owned by Tulsa-based WPX Energy burst open and showered a plume of contaminants on the home where Dee George; his wife, Penny Aucoin; and their two children slept.

George, a Navy vet and former school bus driver who still lives on the land south of town where he grew up, has watched as the view from his front yard transformed from farmland and alfalfa fields to a maze of well pads, heavy-duty pipes, valves and flare stacks sprouting from the earth.

On Jan. 21, George and his wife were jolted from bed at 2:30 a.m. by a deafening roar from the well pad just 100 yards from their front porch. When the couple rushed outside, they were doused with produced water, a chemical-laden waste product spewing from the ruptured line.

“It was just raining down chemicals on us,” Aucoin recalled. “It smelled like gas, it was burning our skin and our eyes, and all I could think was ‘Oh my God, my animals!’”

The leak went on for almost an hour, and by the time emergency crews shut off the pipeline, the family’s property had been thoroughly soaked in a yellowish fluid. George and Aucoin had to euthanize their chickens and one of their dogs. The couple said they and their children have suffered debilitating health problems ever since.

“You smell that?” George asked on a recent day while standing next to the well pad where the pipeline exploded. A steady hiss emanated from the wellhead, wafting a strong gas-like odor through the air. “We’re breathing whatever that is every day.”

The incident at George’s home is not typical. But leaking wells, chemical exposures, spills and other accidents happen regularly, and require expensive cleanups. Preventing accidents is also expensive. Environmental groups fear that the recent crash in oil prices will leave operators unwilling or unable to step in. That could trigger a rise in pollution and an increase in orphaned wells.

More than 700 wells have already been abandoned in New Mexico, prompting state officials to seek a federal bailout to cover the massive cost of capping them. That process can carry a price tag of hundreds of thousands — or even millions — of dollars per well, costs that the state must cover out of its own pocket.

Regardless of the risks, politicians from across the state’s political spectrum have embraced the Permian boom as the ticket to a better New Mexico.

“We will finally put our great wealth to work at perhaps its most meaningful purpose: comprehensively changing the dynamic of early childhood education in this state, forever,” Lujan Grisham said when she introduced the 2020 budget in January.

Two weeks later, the pandemic officially arrived in America.

The house of cards

On April 20, West Texas Intermediate, the U.S. oil benchmark, fell not just slightly below zero: It plummeted roughly 300 percent, to almost $40 below zero, before bouncing back to positive territory.

“What we’re seeing is not an oil bust. This is an everything bust,” said Ryan Flynn, executive director of the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association and an optimist when it comes to the Permian. “This is still some of the best real estate in the world for oil.”

Prices have recently been on an upward trajectory, he noted: As of June 28, the benchmark was at $38.49 per barrel. As soon as the pandemic starts to ease, this side of the Permian will be back in business, Flynn and other insiders predict.

Some economists, on the other hand, warn that the state and the oil and gas industry might never be the same. “We’ve been hit by a double whammy,” Jeff Mitchell, director of the University of New Mexico’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research, said of the virus and the oil slump. The Carlsbad region is “holding up OK,” and the number of rigs operating in the basin hasn’t fallen as sharply as in other places around the country. But if a recession follows, he said, it will upend the economy in unpredictable ways.

The best-case scenario? Demand will quickly rebound.

The worst possible outcome: The pandemic will drag on long into the future, oil prices won’t recover quickly, and oil and gas companies will start to slide into bankruptcy, damaging the region’s status as the El Dorado of oil.

No one knows how long Carlsbad can survive without the oil wells pumping. The current stall in demand has largely hit drillers and contract workers from out of state. Mom and pop operations, most of them based 75 miles north in the city of Roswell, are feeling the pinch more than Houston-based giants like Exxon and Chevron, but they have managed to hang on for now, industry observers said.

Whichever scenario comes to pass, one thing is certain: New Mexico bet the farm on the Permian and drew a bad card. Carlsbad — which still has two potash mines, its tourism industry, the WIPP facility and some oil and gas work — might be managing the crisis. But without the oil and gas gravy train, the state government might not fare as well. Its moonshots could be grounded.

Most economists and lawmakers say they expect a $2 billion to $2.5 billion budget shortage in fiscal year 2021 — a 30 percent decline in revenue from prior projections. “For the last two years, they’ve been talking about an oil boom they thought would last 20 or 30 years,” even though history shows the oil and gas industry doesn’t work like that, said Jim Peach, a retired economist at New Mexico State University who advises Carlsbad officials on the oil boom. “I tried to warn them,” he said.

On June 18, the state legislature launched a special session to address the sudden budget shortage. The revised budget, signed by Lujan Grisham on June 30, cuts spending by roughly $415 million. Most state agencies will see a 4 percent budget reduction, and educators will now get a 1 percent raise as opposed to the 4 percent raise that passed in February. Lujan Grisham rejected steep cuts to the free state college program and preserved funding for early childhood education. New Mexico will draw on cash reserves and federal funding for “revenue backfill,” the governor said.

Land Commissioner Richard, among others, is hoping the bust forces New Mexico to start transitioning to green energy. “There’s always going to be someone scratching at the ground in the southeast part of the state,” she said. But the Carlsbad region is “phenomenal” real estate for wind, solar and other renewable energies. In the future, it could become the home of a healthier kind of boom, she said.

Longtime Carlsbad residents, for their part, aren’t really worried about the future. They are more concerned with their lives right now.

A return to smaller times

That May night at the Lake Carlsbad Beach Park, Trujillo and his cousins complained about their reduced hours at work, from 90 down to 40. It’s not easy to lose more than half your salary, Trujillo said.

On the other hand, they didn’t have much sympathy for the transient oil workers who’d lost their jobs. By most accounts, thousands of them left town when the pandemic hit and the oil boom ended. Maybe Carlsbad would be better this way — more like the old days, the men said. “It used to be that when you walked around, you knew everyone,” Trujillo recalled.

As their shadows stretched out before them, Trujillo’s aunt and uncle arrived with their own camp chairs. The family sat talking. The kids ran up to grab another slice of pizza and pet the puppy. “We’re not here for the boom,” Trujillo said. “This is our home.”

Rachel Mabe’s work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Paris Review, Oprah Magazine, among other publications. She received a grant from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project to support a story about foreign teachers in American classrooms for the fall 2020 issue of Oxford American Magazine. Originally from Miami, she moved to New Mexico from Pittsburgh where she completed a graduate degree in nonfiction & journalism. She also has a master’s degree in folklore and American studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a bachelor’s degree from Bryn Mawr College.

Ed Williams has reported on poverty, public health and the environment in the U.S. and Latin America for digital, print and radio media outlets since 2005. He comes to Searchlight New Mexico by way of KUNM Public Radio in Albuquerque, where he worked as a reporter covering public health. Ed’s work has appeared in the Austin American-Statesman, NPR, Columbia Journalism Review, and others. He earned a Master’s in Journalism from the University of Texas at Austin in 2010.

Hitting Home is a project of Searchlight New Mexico, a non-partisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.