A resolution advocating for the creation of an independent redistricting commission is set to return to the legislative session in January 2025. The proposal aims to combat overt incumbency protection and partisan gerrymandering by establishing a transparent and nonpartisan approach to redrawing political district maps.

Currently, the state constitution grants legislators sole authority to finalize district boundaries. The resolution seeks to amend the constitution, mandating the establishment of a nine-member commission with exclusive control over the redistricting process.

Why redistricting matters to New Mexicans

For many, redistricting seems like a technical and distant issue. However, its implications for democracy in New Mexico are profound, says professor of political science Dr. Gabriel Sanchez.

“A lot of folks might not realize the redistricting process probably decides a lot of elections before we even know who the candidates are,” Sanchez said.

One of the most prominent impacts of that is that the legislature draws districts that are “safe” for incumbents, which discourages competitive races. When districts are redrawn to favor incumbents or to ensure incumbents are not paired in one, opposition often opts not to field strong candidates — or any candidates at all — in “safe” districts. Voters in these uncontested races are often left feeling voiceless, Sanchez said.

“Redistricting probably has more impact on that outcome than anything else,” he said.

This November, New Mexico saw a trend of uncontested races, as 27 out of 42 Senate races and 37 out of 70 House races went unchallenged. That’s 57% of the state legislature.

When asked if he supports an IRC, Sanchez said, “It’s time for us to strongly consider moving in that direction.”

Sanchez said the timing to implement an IRC is crucial and that he’s spoken to experts who recommend getting an IRC on the books before the next Census in 2030, while memories of the contentious 2021 redistricting cycle are fresh.

“If we wait until 2030 the likelihood of passing an IRC is not very high,” he said.

Reviving a controversial proposal

The upcoming resolution is expected to build on Senate Joint Resolution 7, introduced during the 2024 session. According to Fair Districts NM, the new proposal would include revisions to improve the framework for forming and operating the IRC.

Under SJR 7, any New Mexican could apply for an unpaid commission seat. Applicants would be vetted by the secretary of state, who would disqualify individuals with conflicts of interest. A third-party company specializing in random selection would narrow the pool. Political parties could veto up to three applicants before a final randomization process selects six commissioners. Those six members would then choose three additional members through a similar process to complete the nine-member body.

Though the process appears complex, proponents argue it is essential to ensure fairness and impartiality. The proposal also emphasizes community involvement and includes a fiscal impact report.

Despite bipartisan support for SJR 7 (John Block was the only Republican sponsor), the resolution failed to reach the Senate floor after being postponed indefinitely in the Rules Committee. Its House counterpart, HJR 10, was amended in the Government, Elections and Indian Affairs Committee and advanced to the Judiciary Committee, but was ultimately not brought to a vote.

If the resolution passes in 2025, voters would decide its fate during the 2026 midterm elections.

Legislators pushing an IRC

Sponsors of SJR7 and HJR 10 include Leo Jaramillo, William O’Neill, Bill Tallman, Antoinette Sedillo Lopez, Natalie Figueroa, and Republican John Block.

Senators Sedillo Lopez and Jaramillo were reelected. Rep. Figueroa also won reelection, this time as a senator replacing Tallman. O’Neill lost his primary race and Rep. Block won reelection.

Neither Figueroa nor Sedillo Lopez responded to requests for comment about the resolution.

Political Resistance and Challenges

The push for an IRC faces significant political hurdles, primarily rooted in self-interest as passing the resolution would require the Democratic majority to relinquish its control over redistricting.

“It’s asking the Democrats, that have all the leverage right now in terms of numbers in both the House and the Senate, to say, ‘Yeah, we’re going to take ourselves out of the equation and remove the leverage we have as the party in power and turn this over to an unknown entity,” Sanchez said. “That’s a very difficult thing to ask any party to do. So, if this doesn’t pass, I think that will be the reason why, more than anything else.”

Some Democrats have argued that since a majority of New Mexican voters vote for Democrats, an IRC is idealistic and risky, as it could result in maps that inaccurately reflect the state’s political makeup. Sanchez responded to that by saying there is no evidence of that happening in other states that have implemented IRCs.

Others have concerns over inadequate provisions for Native American representation in the proposed framework, echoing critiques of New Mexico’s advisory Citizens Redistricting Committee.

Advocacy groups like Common Cause NM, Fair Districts NM and the League of Women Voters argue that allowing legislators to draw their own districts undermines fairness.

The League of Women voters said that voters should pick their legislators, not the other way around.

Legal and historical context

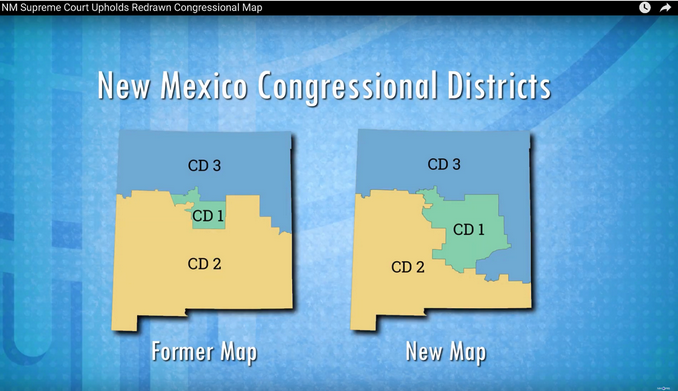

In New Mexico, district maps have remained relatively unchanged for decades, with courts adopting a least change approach during redistricting cycles. However, 2021 marked a period of significant shifts. Democratic legislators rejected both U.S. Congressional and state Senate maps that were proposed by the CRC and finalized their own versions. This action led to accusations of partisan gerrymandering in congressional District 2, a historically competitive seat.

Republican plaintiffs filed a lawsuit in 2022 against Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver and Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, arguing the new districts violated the Equal Protection Clause which is meant to prevent the government from diluting or undermining an individual’s voting power.

Some argued that Democrats redrew the U.S. congressional map with intent to shift Hispanic voters into District 2, while maintaining strongholds in Districts 1 and 3. However, a judge ruled that while gerrymandering was evident, it is not considered egregious (based on the 2022 election results where Rep. Gabe Vasquez (D) won by a slim margin of 7%.)

The map was ultimately ruled to be constitutional.

Plaintiffs appealed and in 2023, the New Mexico Supreme Court upheld the map.

Sanchez said the data from his team’s evaluation of the 2021 redistricting cycle pointed to “buddymandering” — protecting incumbents — rather than outright partisan gerrymandering. There was consensus between CRC members, political leaders from both parties, and experts that Democrats could have done more to advantage their party.

The Citizens Redistricting Committee

The establishment of the advisory CRC was in 2021. Committee members were elected by legislators to gather input from the community and produce several map options for the legislature.

Ed Chavez, a retired Supreme Court Chief Justice and CRC Chair, championed a nonpartisan approach. Chavez led with a mission: To operate with no political allegiances and to ensure the principle of “one person, one vote” by creating compact and contiguous districts that reflect equal populations.

“I got a lot of grief from a couple of senators who said I didn’t do enough to protect incumbency,” Chavez said.

While he acknowledged the value of continuity in representation, Chavez remained firm in his belief that mapmakers should not contort districts to preserve an incumbent’s tenure.

“They can run in a new district. And if they did a good job, they shouldn’t have anything to worry about,” he said.

Chavez’s approach was rooted in community participation. Under his leadership, the CRC held public meetings across the state, some lasting late into the night, to gather input on community, political and economic interests. The process was intentionally inclusive, with Spanish interpreters available for non-English speakers.

“The whole idea was to encourage participation and not condemn somebody because they didn’t speak English fluently,” Chavez said.

The Committee’s engagement with tribal communities was noteworthy. By listening to the Pueblo Indian Council and other Native American voices, the CRC drafted maps that preserved tribal representation and addressed specific requests, like Mescalero Apache’s desire for two districts.

Due to COVID-19, the CRC and community members were forced to rely on outdated Census data from 2010, complicating efforts to accurately reflect population shifts.

Chavez highlighted the stark contrast between the CRC’s approach and that of the legislature. While the CRC prioritized public engagement and transparency, the legislator held meetings that were brief and poorly attended.

“Very few discussions in the minutes of those meetings show anyone speaking publicly,” Chavez said.

Chavez is a strong proponent of an IRC. While. He acknowledges such a move would face criticism and resistance, but thinks it is essential to reduce political entrenchment — the refusal to engage with opposing ideas and the intentional stifling of compromise and competition.

Remaining slightly optimistic about the future, Chavez says the increase in voters registering as “decline to state” suggests the growing dissatisfaction with polarization, which could be a catalyst for redistricting reform.

Although the CRC is currently disbanded, it remains on the books and could play a vital role in the next redistricting cycle. For Chavez, redistricting is not just about drawing lines on a map. It is about ensuring every New Mexican has a voice and a vote that truly matters.