At least some of the people experiencing homelessness in Albuquerque came by bus from cities in nearby states. It’s unclear to what extent those bus tickets were meant to help reconnect people with family or to simply get them out of town, but the practice is adding to a growing homeless problem in Albuquerque.

The rumors

The word on the street — at least the streets of Albuquerque — is that in surrounding states people experiencing homelessness who are arrested for misdemeanor crimes are often taken to court and given two options: go to jail, or get a free ride to Albuquerque.

Doug “Bishop” Anaya is the president of the Hellfighters Ministry Soul Snatchers Rio Rancho unit, a motorcycle-riding ministry that feeds and clothes the city’s homeless every Saturday night.

“What I was told,” Anaya said, “is that it was a judge who was saying either I will put you in jail or we will get you a ticket to Albuquerque. They have shelters.”

“We don’t,” he said.

“We have neighboring states, that will actually send them here,” Anaya said. “The homeless have told us themselves.”

“It’s a service basically, by getting this so called undesirable person— in the way they look at them— out,” Anaya said. “But for you to just put them on a bus and throw them somewhere else? It’s always sad, and leaves an ugly feeling in my stomach, you know?”

Anaya said he’s met at least thirty people who have been bussed out to Albuquerque after an arrest, and that most of them are from Colorado, specifically Denver.

Jacqui Boyd has been a regular volunteer with the Hellfighters for almost four years.

“What is happening right now in other cities or other states, is that once they [people experiencing homelessness] get arrested or get released from prison, or once police officers run into the homeless, they give them the same options,” Boyd said.

Boyd said it would be one thing if the relocation was done through a community organization, non-profit, or program aimed at reuniting individuals with their family or friends. But her concern is that these people are being sent away by law enforcement.

You might say what looks like a get out of jail free card is actually a ticket to a park bench or a sidewalk.

Denver Human Services runs the city’s Family Reunification Program. It has been reported that DHS has spent at least $123,000 dollars on about 540 one-way Greyhound bus tickets since the program started in 2011.

The News Port tried repeatedly to contact DHS and received no response. The public information and records custodian is out on extended medical leave, according to her outgoing voice-message, which also asks that anyone calling does not leave a voicemail.

The department has no listed contact for an interim custodian.

The Denver Police Department told the News Port in an email that it has not sent any person by bus or other form of transportation to a different city in lieu of an arrest.

Technician with the DPD Media Relations Unit Jay Casillas said “we have officers that are part of the homeless outreach team that refers people experiencing homelessness to other organizations or agencies that can help.”

“We do not have an idea why it is being said that Denver Police does that. It may be another jurisdiction in the metro area,” Casillas added.

When asked for an interview, the Colorado Judicial Department responded with a one line email.

“No, this is not happening,” said Public Information Officer Rob McCallum.

Going Home

In addition to Colorado, Anaya mentioned Arizona and Utah as sources of bussed homeless riders. All three states have a form of family reunification program in at least one city. The stated goals of the programs are to reunite homeless people with their families or loved ones through the purchase of a bus, airline or train ticket.

The Society of St. Vincent de Paul in Phoenix, AZ operates a program they call Going Home.

When a person who is experiencing homelessness comes to St. Vincent de Paul, an international nonprofit, they are asked if they have a family or loved on to go home to – even if that person is in another state.

If the individual can provide a phone number of family member or a destination, the society will help them pay for a bus ticket to reach their family or desired destination, said Marisol Ramirez, public relations manager for the society in Phoenix.

“As long as we can confirm that they have a destination, we get that bus ticket,” Ramirez said.

St. Vincent has a monthly budget of $5,000 for the Going Home program.

While the traveler is expected to pay 40-50 percent of the ticket, there are times when the society will cover the entire ticket cost, and they partner with another organization that has a larger monthly budget for bus tickets and can help individuals who cannot afford to contribute.

Ramirez said the society helped transport 347 individuals experiencing homelessness in 2018, and had already helped 146 people in 2019.

The society, however, does not require individuals they help actually be reunited with a family member or loved one. If the individual finds a shelter in another city or state that can be contacted and will accept them, St. Vincent will help them get there.

Though the individual would still be experiencing homelessness at their destination, Ramirez said “when there is a roof out there to put over someone’s head, why wouldn’t we choose to help house this person any way we can instead of sending them back to the streets?”

Albuquerque’s reality

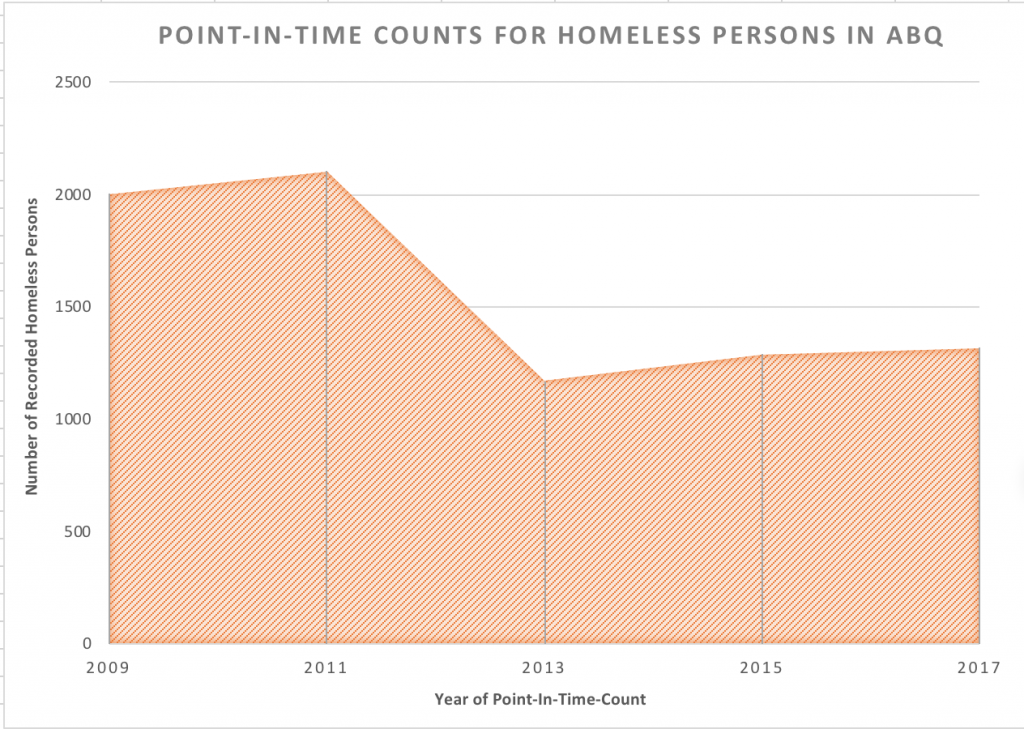

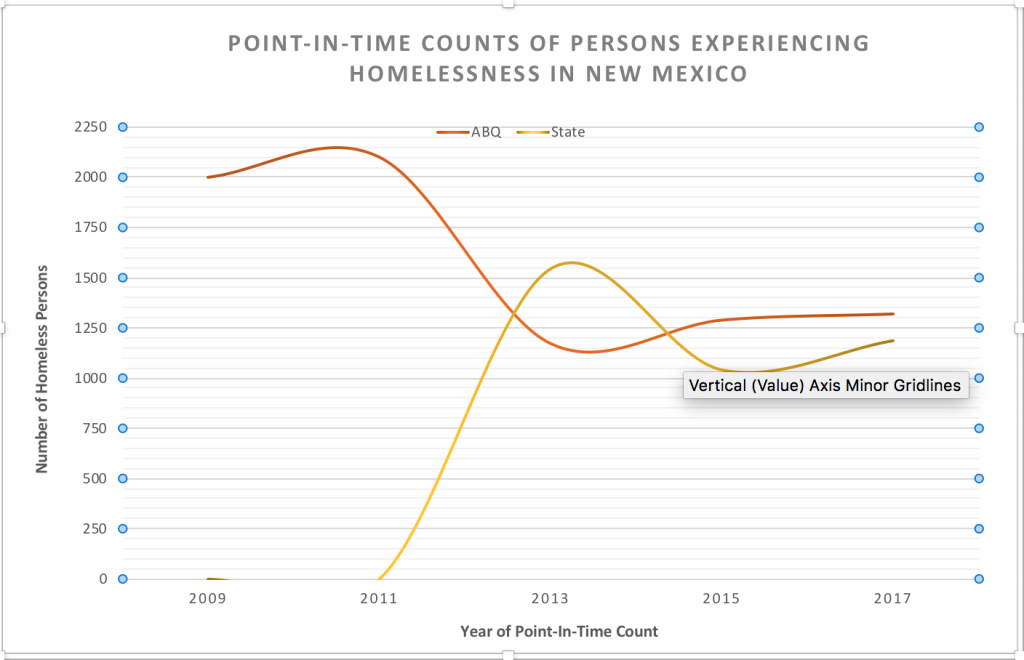

Every two years, the New Mexico Coalition to End Homelessness conducts a one night census of people on the streets or in shelters. It’s called the Point in Time Count. The 2019 count is not out yet. The 2017 count reported 934 sheltered individuals and 384 unsheltered individuals. Of the total population surveyed, 379 self-reported as chronically homeless, an increase of 119 individuals from 2015.

The 2015 point-in-time count showed that Albuquerque’s homeless population had declined by almost 950 individuals between 2011 and 2013, but the city still accounted for more than 75 percent of the homeless population state-wide.

After the dramatic drop five years ago, the city’s homeless population has been increasing.

Lisa Huval, deputy director of Family and Community Services for the City of Albuquerque, said the increase could be attributed simply to better counting methodologies.

“There was an increase from 2015 to 2017 in the number of unsheltered folks,” Huval said, “but I think that means we also did a better job counting unsheltered people in 2017.”

Huval said the number one solution to homelessness is finding homes for those experiencing it. The city is using a two-fold approach to tackle just that.

“We know that we need more emergency shelter beds for people experiencing homelessness,” she said.

The city announced in February that $300,000 dollars would be committed by Bernalillo County to keep the city-owned Westside Emergency Housing Center open year-round. The shelter is usually only open from November through March.

“We are actually committed to keeping that winter shelter open year-round because it is large enough that it’s usually able to serve everybody who wants a bed,” Huval said. The long-term goal, she added, is to move the 400 beds at the westside shelter into town.

The city also plans to increase the number of housing vouchers available this year.

Huval said she was not aware of bussing-out programs in other cities or states, and said Albuquerque does not have a state or city-run program resembling a family reunification program.

She said the idea has value, but “if it is just to get folks out of town, then obviously that is problematic.”

A list of city services for those experiencing homelessness can be found here.

You can follow Celia Raney on Twitter @Celia_Raney.