By Aldo Jurado, Andres Torres, Brigid Driscoll, Joaquin Gonzalez, Joey Wagner, Lara Sullivan, Taylor Gibson / NM News Port

The ever-quickening global climate crisis is drawing sharp attention to New Mexico’s long reliance upon oil and gas extraction and the slow speed at which leaders are able to transition to a green economy.

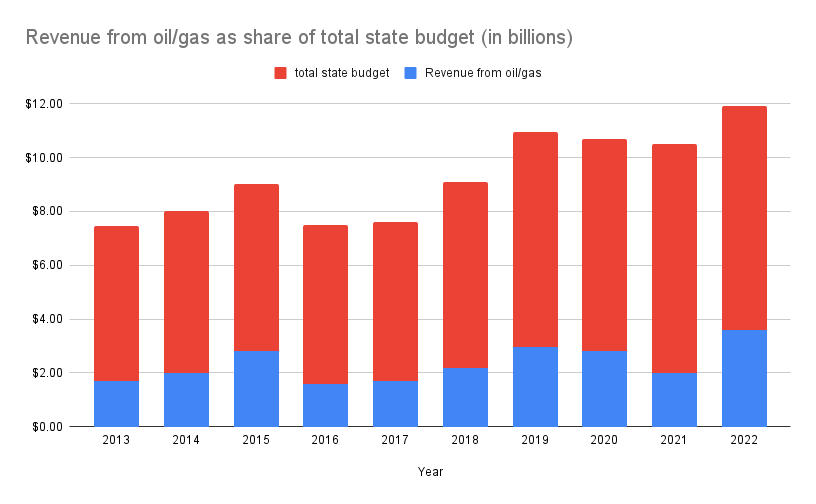

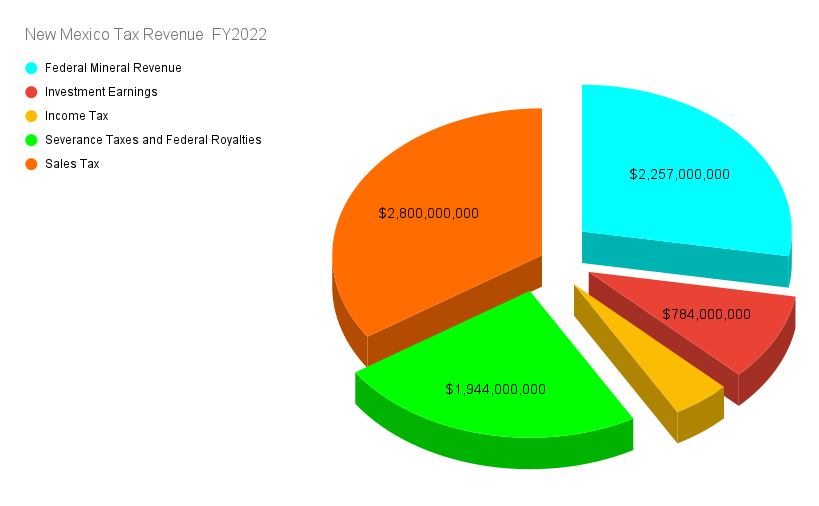

With the state receiving a third of its budget from fossil fuel pay-outs, it would take bold action on the part of politicians – and citizens – to realize a carbon-free future in the Land of Enchantment.

But there is a counter narrative that New Mexico would be foolish to turn away from its fossil fuel heritage.

“If the oil and gas industry pulled out tomorrow, that’s where your disaster would be,” oilman Harvey Yates reportedly told the Valencia County Commission, as he argued to open up oil drilling in the county neighboring Albuquerque.

Yates, his family, and his business are among the largest oil and gas industry contributors to politicians in New Mexico.

The largest single contributor is Chevron, which doled out some $1.8 million in campaign cash in 2020.

“If the oil and gas industry pulled out tomorrow, that’s where your disaster would be”

Harvey Yates

An NM Ethics Watch study found the gusher of oil & gas campaign cash somewhat favored Republicans, but 40% of those industry campaign contributions went to Democrats, the dominant party in state government.

“Remember, in Santa Fe, there’s one oil and gas lobbyist for every legislator,” former state senator Dede Feldman told New Mexico News Port. “The amount that they spend, in terms of PACs, in terms of individual contributions from wealthy oil field executives and their families is tremendous.“

Many are looking to the newly reelected governor of New Mexico, Michelle Lujan Grisham, to lead the charge on climate change.

And with some cause. Grisham was one of only three U.S. governors to travel to Egypt this fall for COP27, the global conference on climate change.

In 2019, Grisham pushed through the state legislature the Energy Transition Act, which requires the state to get half of its energy needs from renewable sources by 2030 and be fully zero-carbon by 2045.

However, Grisham needs to find a way to promote these sustainable industries, maintain and protect jobs in the state, in addition to reversing the environmental problems caused by pollution.

“Oil and gas is such a force to be reckoned with”

Dede Feldman

“I think she’s really done a lot in terms of environmental nudging, nudging New Mexico – which is so grounded in oil and gas and mining – toward a clean energy future,” Dede Feldman said. “It’s very difficult for any governor to do that, because oil and gas is such a force to be reckoned with.”

Feldman concedes, though, that the governor is walking a tightrope and has left the environmental community less than impressed.

“It has to come from the top,” said Executive Director, President and Chief Strategist of New Energy Economy, Mariel Nanasi.

“I don’t think that Michelle Lujan Grisham has gone far enough,” Nanasi said. “I think the biggest problem is that she has had these laws and regulations in place, but there’s zero, I mean, zero enforcement.”

“New Mexico as a state is headed in the right direction,” said Dr. Lewis Land, a hydrologist based at New Mexico Tech who has worked with the petroleum industry in New Mexico, “but the little bit of stuff that we’re doing and the pace that we’re doing it, really isn’t sufficient.”

Over the course of reporting this article, we heard one thing over and over: New Mexico knows what it has to do, but it has barely begun to do it.

New Mexico’s “Dangerous” Reliance on Oil and Gas

New Mexico has been home to a thriving oil and gas drilling industry ever since the 1920’s, when oil was first discovered in the state.

New Mexico’s annual oil and gas production reached 120 million barrels in 1969 – a notable peak at that time, after which production declined for a spell. But drilling increased again in the 1980s through 1990s due to the discovery of more reserves in the Permian Basin.

By 2015, due to new methods of attaining oil and gas using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing – aka “fracking” – production reached a new peak of over 140 million barrels of oil.

According to the Energy Information Association, in 2021, New Mexico became the nation’s second-largest crude oil-producing state, surpassing North Dakota but still behind Texas. New Mexico accounts for more than 11% of total U.S. crude oil production.

Above: Interactive map shows locations of more than 25,000 purportedly active oil drilling sites in New Mexico. Created by Andres Torres / NM News Port

This year, New Mexico reached an all-time high, producing 529 million barrels of oil – a 30% increase from the year before. And next year, it is projected to produce 590 million barrels, according to state estimates.

The oil and gas industry supports thousands of local jobs – though exactly how many has been hard to confirm. According to a New Mexico Oil and Gas Association press release the industry supported over 130,000 in-state jobs. But the number of jobs directly involved in oil and gas production is closer to 15,000, according to the state.

According to the same NMOGA press release, the state budget receives $2.9 billion in its general fund from oil and gas, or 35 percent of the overall state budget this year.

Hydrologist Lewis Land told New Mexico News Port the state is taking a risk relying so heavily on the boom-and-bust industry of fossil fuels.

“It’s dangerous to rely so much, to such an extent, on revenue from fossil fuel production, because of those extreme cycles and the price of oil,” Land said

“When the price of oil is high, everybody forgets about that and they just assume that the good times are here to stay forever. I’ve heard that over and over and over again, and it’s not sustainable.”

Learn More:

Journalists Covering Energy, Environment or Oil & Gas in New Mexico

Jerry Redfern, Hannah Grover, Adrian Hedden, Theresa Davis, Kevin Robinson-Avila, Lindsay Fendt, Laura Paskus

“We Can’t Live Without Water”

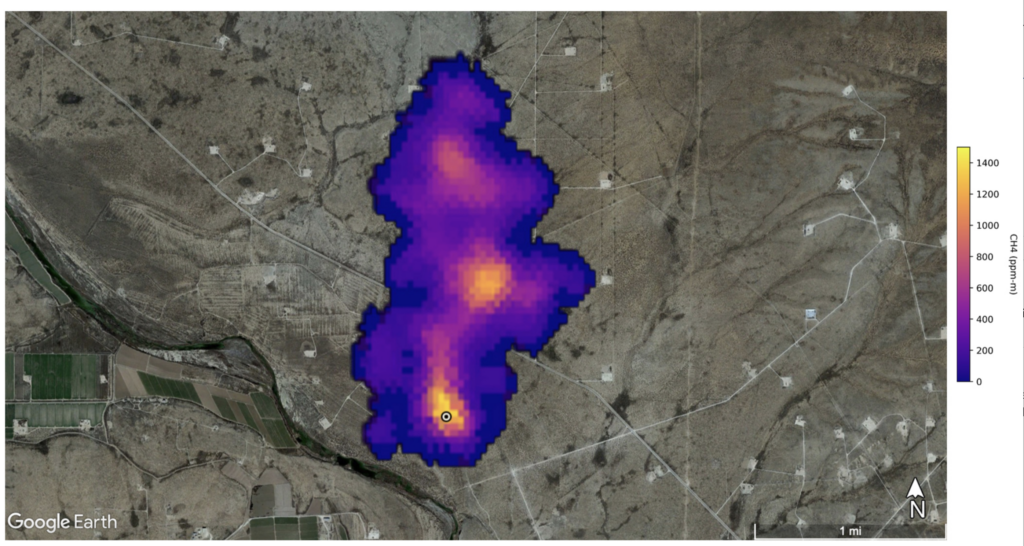

In November, a NASA device on the International Space Station looking for dust and other airborne particles took a disturbing image.

It showed a massive 2-mile long plume of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, over the Carlsbad region.

The EPA requires every site to report carbon dioxide emissions over 250,000 tons in a year, but few companies admit to exceeding that amount.

This plume is partially due to the industry and demand, but also due to the lack of regulation and understaffed regulatory staffs in New Mexico.

Despite New Mexico’s oil and gas sector growing exponentially over the last decade – and more evidence revealing methane and other pollution – there has not been a corresponding increase of environmental enforcement officers required to observe and investigate compliance of the regulations that exist.

“There’s no enforcement,” Mariel Nanasi said, “and without supervision, monitoring and enforcement, there’s going to be no action to protect human health, and the environment and the land and the water. And we can’t live without water.”

“This is an environmental crisis and nothing’s being done about it.”

Mariel Nanasi

In perhaps a troubling warning sign of things to come, the Rio Grande ran dry for the first time in four decades this summer, threatening many small urban farms. Nearly 75% of the river’s water is used for agriculture. The event nearly extinguished the endangered silvery minnow, prompting the U.S. Fish & Wildlife to capture and relocate the remaining fish.

The low water levels of the Rio Grande over the summer have drawn attention to the water requirements of the fracking industry which uses approximately 200 gallons of water for each barrel of oil produced, or over 42 billion gallons per year. This puts a strain on water supplies – some of which arrive from rivers and surface run-off, but much of which comes from the state’s aquifers.

Fracking also creates a by-product called Produced Water, which is defined as fluid that is an incidental byproduct of drilling or the production of natural gas. One of the primary concerns of produced water is its salinity, although there also remains the possibility that the chemicals involved in hydraulic fracking could remain in the fluid, adding to concerns about its safety in its potential reuse.

The Produced Water Act is a New Mexico bill introduced in 2019 that requires the New Mexico Environment Department to draft regulations that address the discharge, handling, transport, storage, and recycling or treatment of produced water.

Wyoming and California have allowed produced water to be used in the production of crops and other agricultural uses, which could be why two New Mexico research groups met with a desalination association in 2018 to explore such options.

Although industry literature claims that fracking is more environmentally friendly than traditional vertical drilling because it requires fewer wells, some say that the threats to the groundwater are more severe.

“Toxic waste, contaminated wastewater going into the ground and into the groundwater. In some cases it’s just a gallon, but others it’s 50,000 gallons” Nanasi said. “This is a crisis, an environmental crisis, and nothing’s been done about it.”

Indigenous Sacred Sites Threatened

In addition to environmental concerns, NM faces the issue of indigenous land and sacred sites being impacted by oil and gas extraction. There are many areas in the state that hold great spiritual importance to indigenous communities, and they consider the sale of their ancestral homelands to major energy corporations an act of egregious environmental racism.

In the northwest area of the state, Chaco Canyon sits as an important spiritual and cultural site, earning status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the 1980’s. Last year U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo, announced a two year ban on new leases while the Bureau of Land Management initiated a consideration of a 20- year withdrawal within a 10 mile radius of the site.

“Now is the time to consider more enduring protections for the living landscape that is Chaco,” Haaland said, via press release, “so that we can pass on this rich cultural legacy to future generations.”

This proposal would not affect current wells and leases in the area.

What are state leaders doing to address climate change in New Mexico?

In the run-up to her reelection, New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham went before a gathering of oil and gas executives in Santa Fe.

She told them she planned to pave the way for fossil fuel energy to become more environmentally friendly and asked that they support her objectives to reduce pollution and attack climate change in New Mexico.

“As the governor, I want to thank you for working alongside us to come up with innovative ways to tackle climate change and air pollution,” Lujan Grisham told the gathering.

“It’s important that we protect New Mexicans and their environment while driving our economy and all of our energy industries forward.”

“Thank you for working alongside us to come up with innovative ways to tackle climate change”

Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham to oil executives, Oct 2021

It was a message that may have earned her votes among her core supporters, but would likely drove voters in oil and gas rich areas toward her Republican opponent.

Still, she won and now would seem to be walking a fine line between the fossil fuel industry that provides billions of dollars in state revenue and the growing green industries of wind and solar that see tremendous opportunity in sunny, windy New Mexico.

Below: According to the New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, New Mexico’s electrical grid relies increasingly on renewable energy — solar and wind — while the state’s decline in coal production over past 10 years is due to the closing of multiple coal mines near the Four Corners region. Chart by Taylor Gibson / NM News Port

In fashioning this year’s state budget, (see her 2023 budget proposal), Grisham aimed to focus on climate change by including $2.5 million ito create a 15-person Climate Change Bureau.

The bureau, part of the New Mexico Environment Department, aims to cut carbon emissions by 45% — based on 2005 levels.

The bureau lists these goals on its website:

- Leading state climate policy development and implementation within the interagency Climate Change Task Force;

- Implementing actions identified in the Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham’s 2019-003 Executive Order Addressing Climate Change and Energy Waste Prevention;

- Tracking and evaluating the State’s greenhouse gas emissions data;

- Implementing the Clean Car Rule and other policies that reduce the greenhouse gas footprint from transportation;

- Initiating the development of clean hydrogen (see the public version of a concept paper submitted to the US Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs program); and

- Supporting climate work within the Environment Department, state agencies, and all other public and private entities throughout the state.

“I think we’re on the right track, but it’s going very slowly”, Lewis Land told New Mexico News Port.

“It’s the same problem we’re having across the world,” Land said, “Policies being written are in the right direction. But there needs to be more done in these areas in addressing the oil and gas transportation industry, as well as residential.”

“In order to combat this, we need climate action,” said Feleecia Guillman with the campus activist group UNM Leaders for Environmental Action and Foresight (LEAF).

“I think that the most demanding thing that we need right now is for our state and city governments to take climate action seriously in New Mexico, because it’s threatening everyone,” Guillman said.

“The most demanding thing we need right now is for our state and city governments to take climate action seriously”

Feleecia Guillman

Of course, as government ramps up a climate response, the oil and gas industry is ramping up its PR campaigns to promote its critical role in New Mexico economics and politics.

“Your primary risk is not geology, so much as it is government,” said the oil magnate Harvey Yates to Searchlight NM.

In the long run, lowering greenhouse gas levels will be achieved by reducing emissions at the consumer level. However, cutting the production-side emissions, which are mainly made up of methane, might have a bigger, quicker impact on reducing the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Earlier this year, the International Energy Agency noted: “Methane emissions from oil and gas operations must be the first to go.”

What else New Mexico is doing on climate change

In an effort to combat the issues of climate change, NM lawmakers passed the Energy Transition Act in 2019. This sweeping set of policies hastens the switch to cleaner and renewable energy, and lead to one of the biggest coal-burning power plants in New Mexico to shut down.

The Sustainable Economy Task Force, Senate Bill 112, was created in 2021. The task force is responsible for creating the plan for making the switch to clean and renewable energy.

The Energy, Minerals, and Natural Resources Department and The New Mexico Environment Department have both passed a list of rules and regulations to maintain the states’ methane and carbon emissions.

The state Interagency Climate Change Task Force was established in 2019 by Executive Order 2019-003 on Climate Change and Waste Prevention, which also contained instructions for agencies on how to incorporate climate mitigation and adaptation practices into their policies and operations.

The New Mexico Renewable Energy Transmission Authority published its New Mexico Renewable Energy Transmission and Storage Study’s results in July 2020, examining the state’s potential for renewable energy.

According to the report, New Mexico has enough potential sources of renewable energy to meet the Energy Transition Act’s deadline of 2030 for utilities and rural electric cooperatives to use 50% renewable energy.

Learn More:

Links to state climate change resources