In Gallup, surrounded by the Navajo Nation, a pandemic crosses paths with homelessness, hate and healers

By J. Weston Phippen | Photos by Don J. Usner | Searchlight NM

GALLUP, N.M. — At the end of the Howard Johnson Hotel’s orange and white hallway, Dr. Caleb Lauber paused by a mirror as if he were lost. The mirror was an invention of the crafty security guards who’d leaned it against a chair, allowing them to quickly see around the corner in case any guests, all COVID-19 positive, should leave their rooms.

Lauber worked 60, sometimes 80-hour weeks, caring for the homeless that Gallup had arranged to shelter at local hotels. He’d seen 500 of these patients in the past month. And now his memory was failing.

“What’s the room number?” he asked his nursing assistant for the second time as they rounded the corner.

Outside, red rock mesas bordered Gallup, a former mining town named after a railroad paymaster. Gallup is a scenic byway on Route 66. The “most patriotic small town in America,” mapmaker Rand McNally dubbed it. The town also calls itself, somewhat inaptly, “the heart of Indian Country,” because while not in Indian Country it is surrounded by tribal lands and the giant Navajo Nation.

Most recently, Gallup and the Navajo Nation became known as the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the West, with infection rates higher than any in the country. There are many reasons for this. But most simply, just as COVID-19 preys on the vulnerabilities in your body, it exploits the vulnerabilities of a community.

Here in the high northwest desert of New Mexico, the virus found a people weakened by poverty, an anemic healthcare system and ingrained historic racism. When, on May 1, Gallup asked New Mexico’s governor to lock down the city, close all streets to incoming traffic and barricade its highway off-ramps, the action carried an implicit message. Gallup is a critical economic hub for the Navajo Nation, a land the size of West Virginia with 173,000 residents and only 13 grocery stores. On weekends, the town of 22,000 swells to double or triple its size — almost all from incoming Navajo shoppers. While the 10-day lockdown was deemed necessary for public health, many Navajo interpreted the order as a clear message: Gallup was closed to outsiders. And in Gallup it was clear who that meant.

Lauber’s role touched on one of the town’s most long-running, controversial problems. Alcohol is illegal on the Navajo Nation, but Gallup’s streets are lined with more liquor stores per capita than almost anywhere in the Southwest. This has attracted an unusually large population of homeless people — anywhere from 600 to 1,500 on a given day — a disproportionate number of whom are Navajo. Some are addicts, and spend daylong benders in town begging for money in parking lots, which is why Gallup has euphemistically referred to this as its “panhandling problem.” But with the pandemic, the panhandlers became a virus-spreading problem. So the town arranged to shelter the homeless in four local hotels, providing them free food and health care.

Some in Gallup didn’t appreciate this deployment of resources. One woman, who described herself as Osage, captured the disapproval in a letter to the Gallup Sun, saying that “the majority of homeless people” have a family somewhere. Why then, she demanded, “don’t we encourage them to return home?

Viral xenophobia

In towns that border the Navajo Nation, which reaches into three states, xenophobia spread alongside the virus. Decades ago, border town restaurants posted signs that read “No dogs or Indians allowed.” Now, in Page, Arizona, police arrested a man who’d urged people through Facebook to use “lethal force” against the Navajo because they were “100% infected.” An hour away, in Grants, New Mexico, Mayor Martin Hicks told The New York Times, “We didn’t take it to them, they brought it to us.”

Gallup’s rumor mill offered up a similar sentiment. All around town, people grasped onto a story of how the spread of the virus was traced to one person: a homeless man, presumed to be Navajo. Police had delivered the man three times in one week to Na’Nizhoozhi Center Inc., a local detox facility, where he came into contact with more than 170 people. That man and the others then passed the virus throughout the community, overwhelming the hospital where Lauber worked, the theory went. Patient records are protected, so the details can’t be confirmed. But the story raised an important question here: If the town had resolved its homeless problem years ago, would it have slowed the virus’s spread?

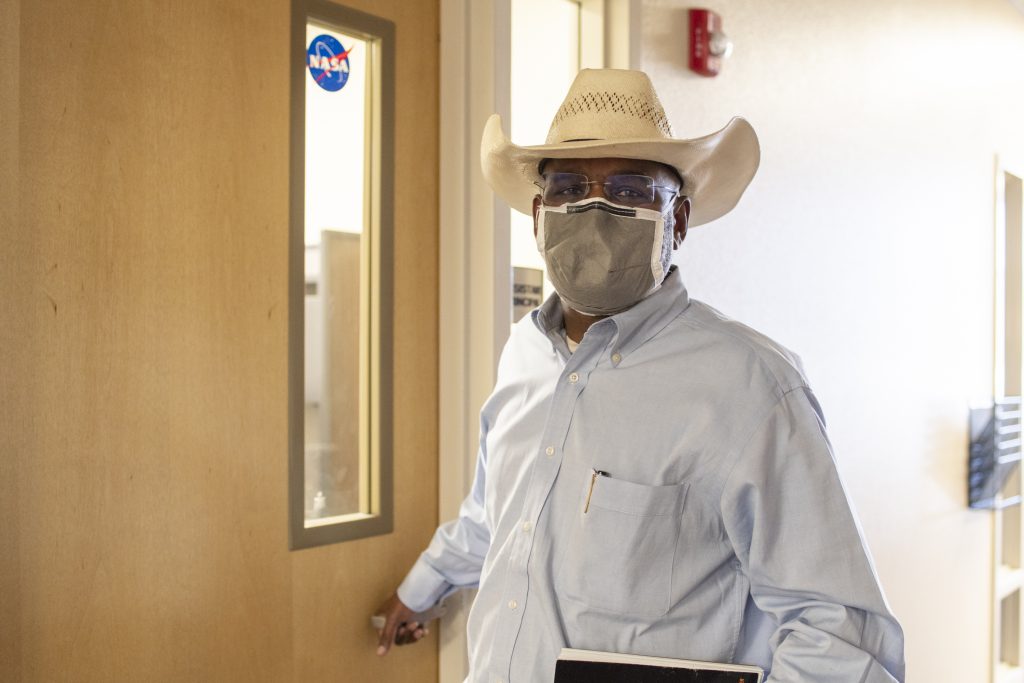

Lauber’s job placed him at the foot of that question. The 59-year-old is the director of community health at Rehoboth McKinley Christian Healthcare Services, the only general hospital for 110 miles. It’d been his job to visit rural communities, and the impoverished towns, hidden in the juniper hills, reminded him of his own childhood home on the reservation.

Lauber studied medicine at the University of Arizona, then worked in private practice in Phoenix. Three years ago, he returned to Gallup to look after his mother, and since returning it seemed that little but the storefronts had changed. In the 1970s, a Native American activist had kidnapped Gallup’s mayor for refusing to limit liquor licenses to the bars that sold to the Navajo. And all these decades later, the town still blamed the Navajo Nation for the panhandlers; the Navajo still blamed Gallup.

Watching Lauber, it was easy to forget the pandemic or the risk that caring for the infected posed to him. It was soulful work for the Navajo man. As he tested patients for diabetes or hypertension, Lauber greeted them as “brother” and “sister.” In the hotel’s parking lot, he placed a face shield over his eyeglasses, slid his lithe frame into a protective hospital gown, then stretched yellow industrial cleaning gloves up to his elbows. When he tested the hotel security guards for COVID-19, he teased the men whose eyes teared as he pushed long swabs up their noses. He made a point to praise the women’s resilience.

Up the stairs from the hallway mirror, Lauber knocked on a door. A skinny arm reached through the frame, the man hidden in darkness. “How are you feeling today?” Lauber asked.

“Just tired and exhausted,” the man said.

Lauber read from a sheet: Had the man visited the detox center recently, or Tuba City or Kayenta on the Navajo Nation, all loci of the virus? Did he have diabetes, a disease that could worsen the virus’s toll? Did he have anyone to stay with?

“No,” the man said softly.

“Do you have any history of drug use?” Lauber asked.

“Just alcohol.”

“Have you ever had withdrawals?”

“Like, four years ago,” the man, 23, answered.

Lauber told the patient he had a few rough days ahead. The nursing assistant, Shaniya Wood, placed a pulse oximeter on the man’s finger to read his blood oxygen levels. Lauber and Wood had personally paid for this device — as well as the blood pressure cuff, stethoscope, medical masks and Lauber’s comically large gloves. They used homemade hand sanitizer that Lauber had learned to mix from a YouTube video, because even under normal circumstances his hospital was strapped.

This was partly why, before he’d come to the hotels, Lauber and about 25 of his colleagues had staged a walkout across the street from Rehoboth McKinley, where hospital president Robert Conejo earned $650,000 a year. In late March, just as the virus took hold, Conejo — who has since been fired — laid off 17 nurses at the 60-bed facility. Standard care practice calls for a ratio of one nurse to every three or four COVID-19 patients; at Rehoboth, some nurses oversaw more than double that caseload.

https://public.tableau.com/views/hittinghome/Dashboard12?:language=en&:display_count=y&:origin=viz_share_link

One patient had already died as a result of what staff physicians called gross mismanagement; another suffered severe brain damage from an improperly adjusted ventilator. So across the street from the hospital, the doctors and nurses held protest signs. Lauber stood to the side as the area’s state senator, George Muñoz, pleaded to a few news cameras. “I’ve sent a letter to the governor telling her we’re dealing with a health care crisis,” Muñoz said. “I don’t know what else to do but beg. And if I have to, I’ll beg.”

Lauber knew he could lose his job for joining the protest. And at the hotel that thought briefly cracked his jovial exterior. “It’s such bullshit,” he said. “I’m exposed to the virus every single day — every single day.” Some homeless patients, agitated and unused to being confined to rooms, spat and cursed at him. When he finished work at the hotel, he’d spend another two hours at the hospital logging records into three different systems: for Rehoboth, the Indian Health Service and the State of New Mexico. At times, it felt as if he’d been sent to war with nothing but a pat on the back, one man salving a problem the town ignored.

Gallup has the highest poverty rate in New Mexico — a state with one of the highest poverty rates in the country. The town is the only economic hub within 100 miles, but after the 2008 recession its retail sector withered. The coal mines that once drew immigrant labor have nearly collapsed. Gallup’s 30-year economic plan now leans heavily on tourism, with the town branding itself a kind of desert trading post, where families can window-shop Native American jewelry on the historic main street and feel a Native vibe without ever driving onto a reservation.

Gallup’s other major revenue source is the Navajo. Native families who live three hours on average from a grocery store come here to fill their trucks with food, water and supplies. But with the lockdown, the parking lots at Walmart (one of the busiest in the state), Home Depot, McDonald’s and Taco Bell, were empty. As was the historic downtown.

The economic toll was especially troubling for Gallup’s new mayor, Louie Bonaguidi, who was sworn into office a week earlier, on April 30. “This lockdown is killing us,” he said from behind his office desk, wearing a bolo tie, his hands resting on a newspaper that tallied the latest coronavirus infection rate. “We need to get our business open.”

On his first day in office, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham had called to congratulate him, then quickly apologized: “We’re closing down your town,” she said. Bonaguidi’s own businesses, including a leather repair shop his Italian immigrant father started in 1924, were forced to lay off employees, almost all of them Navajo. And while it was the previous mayor who requested the lockdown, Bonaguidi couldn’t risk letting thousands of families, including some of his own workers, contract COVID-19 as they shopped in Gallup. So he went along with the decision. “At this point, the virus decides everything,” he said. “We’re all kind of flying blind.”

Many of Gallup’s decision-makers seemed to be grasping at well-meaning solutions, with little time to weigh unexpected consequences. For example, after the detox center outbreak, the outgoing mayor — Jack McKinney, then in his last month in office — banned liquor sales at convenience stores. When the homeless then turned up at the town’s grocery marts, rather than leaving town to buy alcohol, Gallup called on the National Guard to monitor the parking lots.

Bonaguidi now faced similar, unforeseen consequences after the lockdown. His phone vibrated with calls from angry ranchers whose wire fences were cut as desperate people found backroads into town. Gallup had delivered water to the outskirts during the lockdown, Bonaguidi said, though even this simple act demanded almost absurd coordination. Since the Navajo Nation was federal land, the U.S. first needed to negotiate the water delivery with the state, then with McKinley County and finally with Gallup itself — which in turn had to deal with the county because, legally, the city can’t operate outside municipal limits.

To emphasize how complicated this patchwork of authority can become, Bonaguidi cited an example from his time as a city councilor. Several families who lived near the interstate highway had no running water. Though the road was technically within municipal limits, the families’ parcel itself was on tribal land, traded with the Navajo during construction of the southern transcontinental railroad in 1880. “For years we got criticized — why can’t you get water to those people? Well, we couldn’t get a right-of-way to build,” Bonaguidi said. Gallup couldn’t trench a water line across the street, he explained, unless the Navajo Nation, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and a handful of federal agencies signed off. “So for 60 years these poor people have had no running water.”

Navajo Nation land, while sovereign, is held in trust by the federal government. And it’s no secret that the government has reneged on its promises to be a caretaker. Some 30 percent of Navajo still live without running water, in part because the government has cut them out of every major water project in the West. In remote areas, no street signs mark the roads. The Indian Health Service, the major health care provider, expends $3,332 per Native patient, compared to the federal government’s national average of $9,207.

“The bureaucracy is so big nobody knows how to tackle it,” Bonaguidi said, adding again that the town itself was flying blind. The walls in his office were still bare. He’d had no time to hang pictures yet.

Deliverance for the hungry

Since the virus arrived on the Navajo Nation in early March, its president, Jonathan Nez, seemed to be everywhere at once. He’d delivered firewood, food, diapers and bottled water to almost every corner of the land. When Gallup locked down, a decision Nez endorsed, he passed out fresh vegetables and cleaning supplies 10 miles south of town. And where Nez could not be, there were people like Sam Bryant, a Navajo driver with the nonprofit Southwest Indian Foundation, stepping through the cracks of bureaucracy.

Early one morning, Bryant drove west on Interstate 40 past the town of Manuelito, named for the leader who resisted the U.S. Army’s war against the Navajo, a brutal campaign that included the Long Walk, a 300-mile, 18-day forced march from Fort Defiance to Fort Sumner, which killed at least 200 men, women and children. “That’s how I got my last name,” Bryant said. “The guy at the fort couldn’t understand my ancestor’s real last name, so he wrote Bryant.”

In the truck trailer he hauled 100 boxes filled with donated bread, water, flour, toilet paper and hand sanitizer. After half an hour, he turned onto a road bordered by copper-barked ponderosa pine, then parked at an empty rodeo pen in the town of Oak Springs, 34 miles west of Gallup.

Seven women holding clipboards approached from under a white canopy. As community health representatives, they spent their days going door to door across Navajo land to check on patients and deliver medicine. Now, with the pandemic and Gallup’s lockdown, they tracked empty fridges to see who was going hungry.

A line of cars stretched from the dirt rodeo grounds a couple hundred yards to the main road. At least two dozen had arrived early. As Bryant loosened the trailer straps, healthcare supervisor Stephanie Benally wrote the name of each family on her notepad. As each vehicle stopped at the trailer, Bryant and the women loaded it up. Then the next pulled forward. The line grew as new families arrived.

Seven years ago, Benally was assigned to Oak Springs. And more than anyone, she knew how the virus could devastate a community. Diabetes afflicts one in five Navajo, and she’d already spent much of her time here either testing for the disease or delivering medicine to manage it. Many families washed their hands in the same bowl of standing water.

Benally had visited a different Navajo community nearly every day recently to deliver supplies. “People will start lining up at six in the morning and wait until three to get food,” she said. “A lot of people were frustrated about the lockdown, especially the last-minute notice.”

After an hour, only a few of the 100 boxes remained on the trailer, and those were for elderly shut-ins. Still, the cars arrived. Benally could only apologize and explain that the food had run out.

The peak is still ahead

While the rest of the country decides how to safely reopen, the virus is expected to peak here in mid-June. More than 9,600 people on the Navajo Nation and in the county surrounding Gallup have been infected, nearly double the rate of New York City. At least 470 people have died, the majority of them Navajo. In late May, Doctors Without Borders, known for operating in war zones overseas, dispatched a team to the area.

To clear beds in Gallup’s ICU for the coming wave, the National Guard converted Gallup’s Hiroshi Miyamura High School into a health care overflow center. At the school’s front entrance, plywood closets with medical protective gear stood beside the trophy case. Behind a set of gym doors, 20 beds filled the basketball court, where a handful of recovering patients gritted through the last throes of the virus. Down the hall, Sanjay Choudhrie sat behind a desk in the principal’s wing, itching at the salt-and-pepper beard under his mask and waving a cell phone.

Choudhrie has no medical background. But when he learned the pop-up clinic needed a director, he applied. A few days earlier, his medical operations chief had tested positive for COVID-19 and Choudhrie now scrambled to find backups for every staff member in case they, too, became infected. He was also chasing down supplies. “It’s gowns, it’s face masks, it’s gloves. And on any day one of those will run low. Today it’s gloves.”

Choudhrie had a unique perspective on Gallup. He’d grown up in a rural town in India, studied in Berkeley, California, and moved here when his wife found a job at Rehoboth hospital. Choudhrie also had a unique understanding of the pandemic’s spread. For 13 years he’d run Care 66, a Gallup nonprofit devoted to easing poverty. “There’s a lot of depression and desperation in this region,” he said. “And it’s hard to point to one thing. It’s the whole structure.”

Choudhrie was not so arrogant as to think he could solve the root causes of poverty. But he believed he could provide shelter for the town’s homeless people — something that, in hindsight, might have altered the course of the pandemic. In 2012, he had bought an abandoned hotel downtown where the homeless could live regardless of sobriety. The townspeople of Gallup resisted: Wasn’t that encouraging these people to stay? Without support from the community, Choudhrie ran out of funds. His nonprofit closed in 2018. “My opinion is that the town has failed its citizens by its refusal to take action,” he said.

Conversations in Gallup have a way of returning to the homeless. Whether the story of one homeless man spreading the virus through town was true or not, it seemed to serve a purpose. Otherwise, how could you make sense of COVID-19 tearing so easily through the area? How to explain 60,000 people without running water to wash their hands? A town’s hospital on the verge of collapse? A region struggling with Third World poverty in the wealthiest nation on Earth? And how to explain a mysterious virus upending it all?

Those questions offered no comfort. The homeless problem, at least, made sense.

J. Weston Phippen has reported on the Southwest, primarily focused on the border and the U.S.-Mexico relationship, for 10 years. He was a former staff writer and editor at Outside magazine and The Atlantic, and his writing has also appeared in publications like Mother Jones and Rolling Stone. In 2016 he was a finalist for the Livingston Award for international reporting. He moved to New Mexico three years ago, and lives in Santa Fe. Email Weston

Hitting Home is a project of Searchlight New Mexico, a non-partisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.

Hi, I’m the (first-ever) Professor of Practice in Journalism at University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. So I’m very involved in helping students learn multimedia journalism. Before New Mexico, I was the 2012-2013 Reynolds Chair in Ethics of Entrepreneurial and Innovative Journalism at the University of Nevada, Reno… and, before that, a 2011 Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University. I’m also very active as a consultant, having spent over 25 years as a news director. My website is http://www.mikemarcotte.com or on Twitter: http://twitter.com/michvinmar