When non-English speakers find themselves in the court system, they should, according to due process, have the right to a court-certified interpreter.

In New Mexico, that’s not always the case.

According to Naomi Todd-Reyes, a court-certified Spanish interpreter, the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) is taking prospective interpreters who got 55 to 69 percent on the certification exam and calling that second-tier certification. Todd-Reyes says that’s lowering the bar for court interpreters.

“Knowing that these people are passing with a 55 to 69 percent, does that mean that’s the amount they’re getting correct in these hearings?” Todd-Reyes said.

These second tier interpreters are called Justice System Interpreters (rather than Court-Certified Interpreters), and there are currently six of them listed in the New Mexico Center for Language Access directory.

Justice System Interpreters (JSIs) are paid less but are hired more readily because of the court’s dwindling budget, Todd-Reyes said.

“Some of us have felt like our workload is going down, and we find out through other sources that these JSIs have more work than we do, which is kind of messed up,” she said. “They’re cheaper, but also our position is like, certification means something. You don’t say someone’s almost passed the bar exam so they can pretty much represent you in a court of law.”

One court-certified Arabic interpreter, Mohamed Ali, says he knows someone with very limited ability who was called to interpret cases.

“He’s really not qualified to be there. It breaks my heart because all you have to do is go in there and record what he’s saying, and you know that translation was not accurate,” he said.

Ali points to another instance of an unqualified interpreter working.

“This guy was there in one case recently, and the city attorney asked him ‘are you certified?’ and he said ‘yes,’ but he’s not! He’s not certified — I know that for a fact — and he told me he failed every single test,” Ali said.

Paula Couselo, the senior statewide program manager for the AOC, said JSIs are only used when court-certified interpreters aren’t readily available.

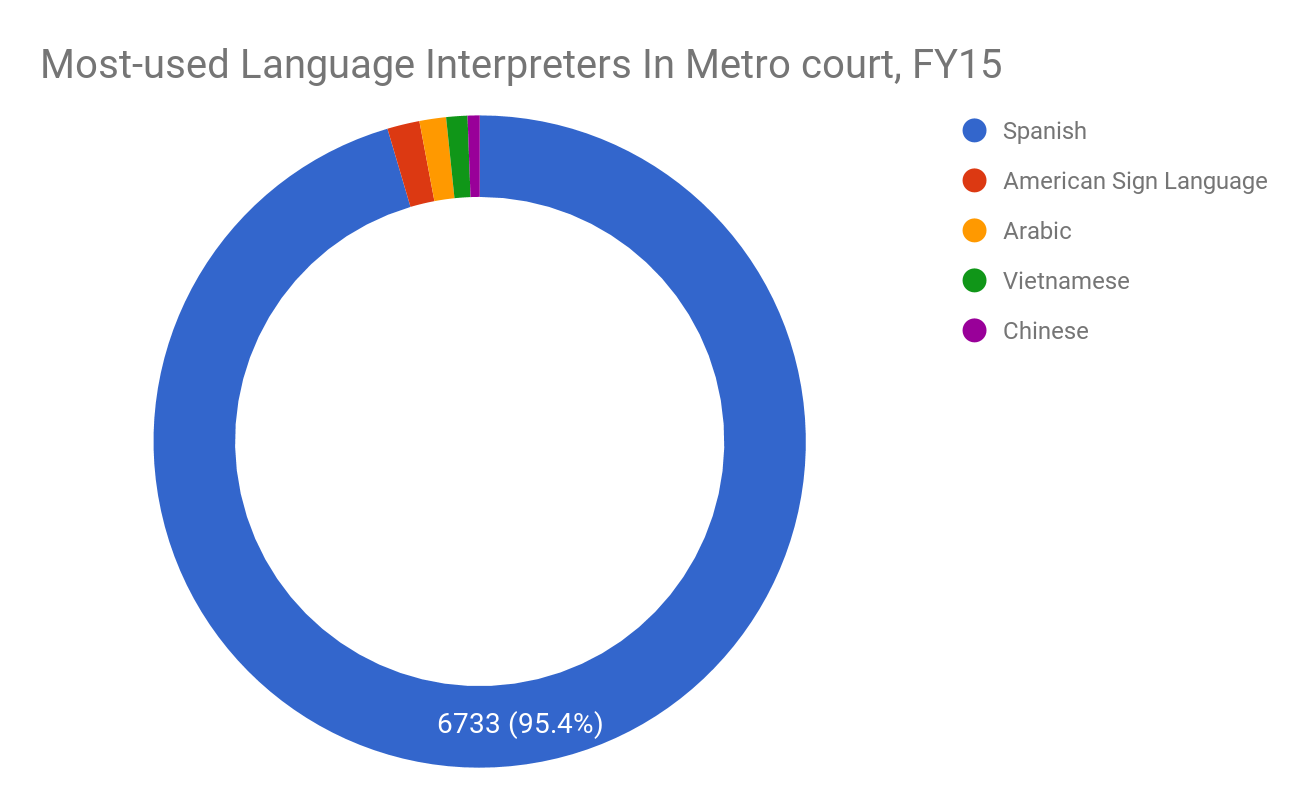

“The preference is always to provide certified interpreters. That’s what we strive for,” Couselo said. “Currently we cover about 95 percent of what’s done in court with certified interpreters, but there may be exceptions where an interpreter may not be reasonably available.”

Factors that contribute to demand for JSIs include physical location, New Mexico’s use of non-English jurors, and the need for more interpreters overall. JSIs aren’t allowed to do every type of case and many go on to become certified, Couselo said.

Both Todd-Reyes and Ali claim, however, that the AOC is poorly managed.

“I have more degrees than anybody working in the entire office over there,” Ali said. “New Mexico– non-stop harassment. [A manager] who has never been a translator or interpreter is giving a lot of interpreters a headache.”

“The AOC really only cares about the budget and cutting costs; that’s just where all the focus is,” Todd-Reyes added.

Todd-Reyes said the JSI program could be used to encourage people to practice and give them a clear path to eventual certification.

“I’m not totally against it– they’re having some opportunity to practice in low stakes settings, but the issue is that they’re using them to kind of replace us and putting them in hearings that they shouldn’t be doing,” she said.

The whole process is faulty if people don’t have a qualified person interpreting for them, Ali said.

“Some of their rights have already been compromised before the case starts; that is sad,” he said. “That should not happen in the U.S. We deserve better.”

For more follow Angela and Alissiea on Twitter