Editor’s note: It’s no secret the tech world usually doesn’t score high marks when it comes to diversity. Women and minorities are underrepresented in jobs that focus on programming.

Students from three UNM journalism classes looked at these groups, a recent hackathon for Native American youth, and a new movie about the gender gap in computer science.

By Marino Spencer / NM News Port

Native American students Twylastar Warkie and Madison Castillo laugh and gather in front of a Macbook computer.

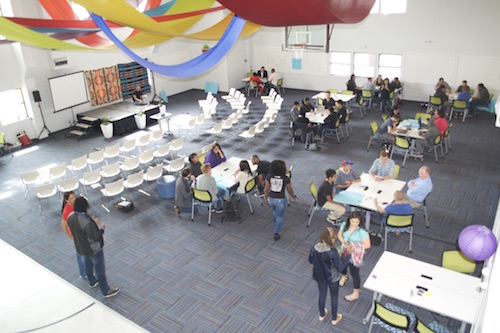

They are playing an early version of a game they designed with help from some coding mentors at a recent hackathon at the Epicenter in downtown Albuquerque.

The women represent a small part of the nation’s overall tech community. Women — and minority women in particular — are overshadowed in a field that’s predominantly white and Asian males.

“The system that we’re in says minorities have to prove their worth,” said Kalimah Priforce, headmaster C.E.O of Qeyno Labs. “[It’s] called a whole lot of names but the nicest thing they can come up with is meritocracy.”

Priforce teaches coding languages to lower-class communities through hackathon events and coding bootcamps.

Qeyno Labs and Native American Community Academy (NACA) partnered with intentions to add more minorities to the tech industry. They held an event in late April called the My Brother’s Keeper Hackathon. This was the first event aimed towards Native youth.

Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans and other minorities make up a small percentage of technology jobs in the United States compared to whites and Asians. According to the Qeyno Labs website, African-Americans comprise only 2 percent of the top tech workforce and Hispanics make up only 3 percent. Women make up less than 30 percent. According to this 2014 article, Native Americans lack overall representation in the Silicon Valley tech sector.

Priforce says middle-class white males can “fake it until they make it” but minorities do not have that option. Minorities, he said “have to show we are qualified [and] we have to show our competence.”

Tech industry slowly changing over time

In the early 1990s, computers and the internet were not quite common items. That’s changed dramatically as a majority of people now access information through phones and tablets. The code to make that technology work is crucial.

“Think about like everything that you use on a daily basis, there’s code. There’s code in your car, there’s code everywhere. So the possibilities are really endless,” said Amy Cliett, program director of Qeyno Labs.

Cliett said Qeyno Labs has held hackathons in Oakland, Austin, New Orleans, Atlanta and Albuquerque.

“The idea of our hackathon is we go from city to city we come and . . . get the ball rolling,” Cliett said. “Then we hand it back off to the community to keep things going.”

Cliett said a hackathon includes a community of app developers, graphic designers, innovators and students coming together developing ideas and building apps over the course of a weekend.

“When we started we wanted to make a hackathon a household name,” Cliett said. “If you think about it, it’s like a marathon with coding.”

NACA Students ‘Tap into imagination’

NACA Executive Director Kara Bobroff said NACA worked in conjunction with Qeyno Labs to teach Native American students presentation skills and coding languages at the Epicenter in downtown Albuquerque.

“We want you to create new technology,” Priforce said to NACA students at the hackathon. “We want you to heal the world, we want you to do all these things that tap into your imagination.”

The hackathon was a two-day event teaching NACA students the process behind developing an app. Priforce says learning how to pitch an idea for an app is crucial and will help their confidence.

Bobroff said the hackathon provides another learning tool for NACA students.

“So it’s not necessarily a thing to keep them in school because they’re really great kids and they’re very committed to their education,” Bobroff said. “Once you tap into something that they have a little bit of interest in . . . they can . . . take that and really move in a lot of different directions.”

Bobroff said NACA conducted a focus group asking students about their learning interests. Some students chose to learn coding languages making phone applications and video games.

“For some of our students that’s art, for other . . . students it’s music, for some . . . it’s athletics, and I think this is just one area that will really kind of round . . . out for other students in the school that may have not had that opportunity before,” Bobroff said.

Bobroff said there are three reasons behind the hackathon.

“One is to raise the awareness of what coding, app development or videogame development can be,” Bobroff said. “Two is to connect to the broader community in Albuquerque [with] designers, developers and innovators and three is . . . to say . . . [minorities] have a . . . presence in the tech field.”

Cliett said Qeyno Lab’s “mission is to transform children’s’ lives through technology, education and bridging the gap of the tech inclusion.”

Volunteers serve as code and design mentors

In addition to NACA and Qeyno Labs, Cultivating Coders also provided support for the hackathon. Cultivating Coders runs an eight-week coding bootcamp. They provided mentors for the hackathon as well. Mentors included Aarick Lameman and Craig Benally.

“It’s a perfect opportunity for Native youth to get creative with modern technology,” Benally said.

Benally said learning code “could benefit the Native communities in a number of ways.”

“Someone could design an app for … water resources….solar technology, or wind technology,” Benally said. “Whatever these little kids could think of, the sky’s the limit for them.”

Making an indigenous sports game

NACA student Josiah Villaverde was quiet and shy during his first pitch presenting his sports game idea. But he showed more confidence during his second presentation as he introduced himself as the CEO of Indigenous Games.

Villaverde named his app Indigenous Games 2017, or IG2k17. According to the group’s website, this sports game features Indigenous games such as Iroquois lacrosse, Muscogee Creek stickball, Kamayura Huka Huka wrestling, archery, blowgun shooting, canoeing, and spear throwing.

Lameman helped Villaverde develop IG2k17.

Lameman says the reason behind IG2k17 is that “Native representation in sports video games is either lacking or incorrect.”

“Sports video games have zero cultural options for Indigenous populations,” Lameman said.

“Indigenous Games is going to solve that problem by creating games that are designed around Indigenous culture,” said Elan Colello, CEO of ARVRUS. Colello also helped Lameman and Villavarde develop the game.

Designing ‘Jelly Cat Trap’

Another app developed at the hackathon is Jelly Cat Trap. NACA students Twylastar Warkie and Madison Castillo both came up with the idea for this app.

“You have to survive through this level with cats,” Castillo said. “You cannot shoot at them but you can distract them with boxes or cat toys.”

Ryan Leonski and Shandiin Woodward of Subliminal Gaming helped write code and design the logo of the game.

“The reason why we wanted to create this is we wanted more girls in technology. There’s not many Native American girls in [tech],” Warkie said.

Aspiring coder makes mom proud

As part of the event, NACA student Samara Stevens came up with the app Uni-Emojis. Stevens said the biggest issue with emojis is they do not translate well across different devices. This particular app will allow the user to make customizable and universal emojis that will translate to phones of all platforms. Stevens’ mother, Adriene LaPointe, was present to support her daughter throughout the hackathon.

“It was a surprise,” LaPointe said. “To hear what she was all doing, it blew me away.”

LaPointe said she believes learning code will help Stevens with future school and job opportunities.

More hackathons to come

Cliett said this hackathon is the first step towards more hackathons. The hackathon focused on the students’ ideas and pitches. The mentors mainly wrote coding for their apps.

“We actually coined this a hackathon prep and what we plan to do is have the hackathon classic where we do dig more into code,” Cliett said.

Cliett said the next hackathon’s date is pending but the forthcoming ones will “have finished products that you would be able to see . . . download and buy.”

Bobroff also said there will be other similar events.

“This is the first step to a larger more kind of like longer hackathon which would be …for our kids to start learning the concrete skills around coding, design and development,” Bobroff said.

“So one thing that happens when you apply for a job in technology [is] they don’t typically ask you about your degree or what school you went to, they want to see the work you’ve done,” said Cliett about applying for employment in the STEM field.

“It’s essential . . . that students, especially that’s why we try to start young, they learn the code so the jobs will be available to them,” Cliett said. “There . . . literally . . . out there waiting for people.”

Bobroff said the students’ interest in videogames might lead to app development and make use of “the intersection of technology and solutions . . . that can help our [local] community.”

Cliett said it is possible some students may not “touch anything in technology again” but will gain confidence through their pitches.

“They will remember that they got on stage and they made a presentation and that’s important,” Cliett said.

Priforce said he believes NACA students are innovators and have potential to be a tech mogul like Bill Gates or a leader like Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Innovation is here and it starts with that hidden genius you have in that mighty brain of yours,” Priforce said.

Hear an audio story about the Hackathon produced in conjunction with our partner KUNM News.

New documentary showcases history of women in tech

By Lissa Knudsen / NM News Port

An award winning documentary about why women are underrepresented in computer programming fields was screened at the Guild Cinema as part of the 2016 Albuquerque Film and Music Experience film festival.

After the movie, Robin Hauser Reynolds, the producer/director of Code: Debugging the Gender Gap, a, Skyped in for a 25 minute question and answer session.

In her comments, Hauser Reynolds said marketing for computers in the past was directed at boys, and that while women were early pioneers in computing, the tide has turned away from that.

The movie looks at the history of coding and showed the prominent role that women played in designing the original coding languages. It also explores the reasons why women are no longer represented in computer science fields at the rates that they once were.

Because the demand for computer programmers is growing at a faster rate than colleges and schools can produce qualified graduates, one of the CODE interviewees called this the “Rosie the Riveter” moment in computer programming.

During the Skype session, Hauser Reynolds provided examples of why having more women coders benefits decision making and improve product development. She fielded questions about why young girls seem to change course in their early teens away from computer science and suggested that more be done to bring coding to girls as early as elementary school.

One movie-goer agreed.

“I think it matters how we talk to children, I think it matters what we tell them in terms of what they can do and what they can be,” said audience member Amy Leland.[/vc_column_text][vc_separator border_width=”4″ css=”.vc_custom_1463085955762{border-radius: 4px !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Local groups offer tech education to wide audience

Coding bootcamps and programming classes offer a way for students to gain skills that are likely to land them lucrative jobs. But minorities and women say such classes often are too expensive.

That’s changing in Albuquerque as a growing variety of organizations are pushing to make sure a diverse cross-section of the community has a chance to learn valuable computer skills.

Women in Albuquerque can learn coding through the local chapter of Girl Develop It And minorities have an opportunity through Cultivating Coders, a company that recently won the grand prize at the South by Southwest conference in Texas. Recently the program My Brother’s Keeper Hackathon presented a weekend workshop for Native youth to learn coding skills, as well.

Last year Fortune Magazine conducted an analysis of the employee demographics of 14 technology companies — looking particularly at gender and ethnic diversity. In summary, the magazine found that “minorities accounted for just a tiny fraction of most of the companies’ workforces and no company could say that women made up 50 percent of its employees.” See how the big tech companies compare on the employee diversity on Fortune.com.

Despite those findings, New Mexico’s tech scene is encouraging the growth of coding diversity in the state.

“Equal opportunity to everyone in New Mexico is important, not just to minorities, said Charles Ashley III, president and co-founder of Cultivating Coders.

“We need more women, youth, disabled and veterans in coding. Increase the talent pool in New Mexico and and contribute to the growth of the technology industry in our great state. That’s all part of our mission.”

The Albuquerque based Cultivating Coders is to teaching students programing and scripting languages including HTML, CSS, Javascript, PHP, and MySQL to build web applications and layouts.

Bringing female developers to the forefront

Nyika Allen, who directs community operations for the New Mexico Technology Council and is co-founder of the New Mexico chapter of Girl DevelopIt, says there are compelling reasons to teach more women how to code.

“Actually women have proven to be better developers than men, so we want more women in that space,” Allen said. “Working at the technology council, I want to make sure that happens.”

My Brother’s Keeper Hackathon is a coding event that took place in Albuquerque at the Epicenter on April 23 and April 24 — just before the Gathering of Nations Powwow. The event allowed Native youth the opportunity to team with their peers, professional coders, designers, and innovators to collaborate on new ideas.

Kara Bobroff, the executive director and founding principal at Native American Community Academy, champions the importance of Native youth learning coding skills.

“I think Native youth have such a unique perspective about the intersection of community, language and culture,” Bobroff said.

“A lot of times tribes are responsible for not only leading the governance in a sense of governing and making decisions for their communities but also economic development, education, health, the infrastructure of each of our different pueblos and reservations as well … and I know for a fact that our students will be making those decisions.”

Watching students’ ‘brain change’

One mentor at the event, Michael Kemp, an engineer in San Francisco, traveled to Albuquerque to help at the hackathon.

“I sort of guide these kids along the process that they need to get from an idea to maybe a prototype to a completed product,” he said.

One of his favorite parts in the process of mentoring is “watching their brain change.”

“Because then they get this idea, they’re like, all I have is an idea, and if I act on it I can make it happen, and that’s how people change their lives. They realize that they can just do thing,” Kemp said.

Kalimah Priforce, the headmaster CEO of Qeyno Labs, who helped bring the hackathon to Albuquerque, said the event builds community.

“The work that we do focuses on not just building apps. Building apps is something really cool that the kids are able to produce at the end of our pop up schools, but what we really teach them to hack is isolation,” Priforce said.

“Native youth have their own unique experience around isolation and so what we’re doing is we’re giving these young people an experience, but it’s actually them who will be teaching us what tools they are able to create.”

Follow the News Port on Twitter.