The treatment was simple — three pills a day, best taken on a full stomach — and it cured Gabriel Serna of hepatitis C in eight weeks.

He just had to wait eight years to get it.

In theory, revolutionary medications have made the blood-borne, sometimes-fatal infection curable, so people with the disease need not endure the inexorable and irreversible damage it causes to their livers.

Unless they are in one of New Mexico’s prisons, like Serna was for much of his wait.

That’s because although the state’s inmates have the highest prevalence of hepatitis C of any group in New Mexico — more than four in ten are infected — the prisons are hardly treating any of them: Out of some 3,000 prisoners diagnosed with the disease, just 46 received treatment for hepatitis C during the 2018 fiscal year. They are locked in for their crimes, but the life-saving medications they need have been largely locked out.

Whether or not the prisons are prepared for change, it may be forced upon them. In states across the country, inmates have brought a wave of lawsuits arguing that withholding the latest drugs from them is unconstitutional — and New Mexico could be next, saddling the state with more than $50 million in costs to provide overdue treatment.

State officials have been aware of their obligation to treat inmates with hepatitis C for years. In a television interview in 2016, the Corrections secretary at the time acknowledged that the state might be sued if it didn’t increase drug access in the state prisons. And local civil rights lawyers are already considering ways to push for reform, including litigation.

***

The day after Christmas, Gabriel Serna was alone in a mobile home he’d been fixing up in Albuquerque’s South Valley, not far from the neighborhood where his grandmother raised him. The repairs were one of the odd jobs he has taken to make ends meet since leaving prison. For a 55-year-old with a string of felony convictions and half a lifetime behind bars, it can be difficult to find work.

He lives in the unit next door, which he recently painted with fresh red trim. Gunfire is a regular occurrence on his street, as is drug-dealing, treacherous conditions for a person with an addiction who is trying to stay clean. But it’s what he can afford. “The temptation,” he said, shaking his head. “You’ve got to have a strong-ass heart to be here.”

Like most people with hepatitis C, he couldn’t pinpoint when he was infected — most people who contract it do not experience immediate symptoms and may be unaware they are carriers for years. Scientists didn’t even identify the virus until 1989, at which point prevention efforts like screening it from blood banks could begin, so the baby-boomer generation who came of age before then has five times the prevalence of hepatitis C of younger adults.

When Serna first tested positive in 2001, he reasoned that he might have picked it up when he had a tattoo of an old girlfriend’s name inked over. He had also injected drugs since he was 11, when a neighbor first introduced him to heroin, so there had been ample opportunities to share dirty needles over the years.

But the way the infection is contracted has no bearing on its effect. The virus is insidious, causing progressive liver damage that ultimately results in scarring and then liver cancer or end-stage-liver disease. At the point a patient begins to experience symptoms, they may have just months to live. More than 3.5 million Americans are thought to have hepatitis C and it kills about 20,000 of them each year, triple the number killed by AIDS.

New Mexico’s prevalence is particularly high: researchers estimated that as of 2010, nearly one in forty of the state’s adult residents were infected, 60 percent higher than the national average. And nowhere is the concentration higher than in the state’s prisons, where as of January 2019, 44 percent of people screened positive, according to corrections officials — the highest known share of any correctional system in the country.

That is indicative of the dire circumstances in New Mexico, but also of the state’s willingness to acknowledge it: beginning in 2009, all people locked in its prisons have been offered screening (to which they can opt out, but most accept). Many other states have put their heads in the sand, screening just those inmates who request it, so they have no accurate measure of the extent of the problem.

Until a few years ago, there was a plausible argument that not much would come of the information. The standard drug treatment for hepatitis C was barely tolerable: it took six months, induced side effects like depression and severe fatigue, and failed to cure the patient as much as half the time. But then in 2014 Gilead Science introduced the first of a series of game-changing drugs known as direct-acting antiretrovirals. Suddenly most patients could be cured, with few to no side-effects, in as little as eight weeks.

The drugs were revolutionary and the manufacturers knew it — and priced them accordingly. Gilead launched its first, sofosbuvir, at $84,000 per course of treatment; since then competing therapies have driven down prices but they still run around $20,000. And private and public insurers have proven willing to pay: even at that price, it is cost-effective to immediately cure hepatitis C rather than face its dangerous and costly consequences down the line, when a patient’s only recourse may be vying for a scarce liver transplant.

But correctional health systems across the U.S. have balked. In a typical prison budget, healthcare is among the costliest item after staff salaries, and states face the full cost without assistance from the federal government (long-standing federal regulations bar inmates in both federal and state prisons from receiving coverage under Medicaid or Medicare until they are released, although many of them would otherwise be eligible).

So, prison health systems have erected barriers to treatment, narrowing eligibility to inmates whose livers have already become irreparably scarred. There is a certain logic to prioritizing the sickest people but it means patients must wait for the virus to damage their livers before they can have the infection addressed.

Serna was in the Santa Fe Penitentiary in 2010 when he began seeking treatment in earnest, even before the advent of direct-acting antiretrovirals, and he was quickly rebuffed. “I would put in medical requests and they told me ‘No, sir, you got to have a clear conduct.’”

A set of New Mexico Correctional Department guidelines from June 2018 indicated that they restrict treatment to inmates free of major disciplinary infractions for at least twelve months, on the argument such behavior “indicates an inability or unwillingness to comply with regular programming.” Even a history of multiple minor infractions, as irrelevant to health as “abusive language or gestures,” can exclude a patient from treatment.

According to Serna, “They told me that the best thing to do—because they were not going to treat it, that was the bottom-line—was for me to drink a lot of water and exercise.” He continued to request treatment throughout his sentence, as the new drugs were introduced and became blockbusters in the world outside. Finally, when he neared release, corrections officials changed tactics and pulled him aside for a meeting in the sergeant’s office. “The reason why we’re not giving you treatment, Serna,” he recalled them telling him, “is because you’re going home.”

“I would put in medical requests and they told me ‘No, sir, you got to have a clear conduct.’”Gabriel Serna describing rejection of his requests for Hepatitis C treatment in prison.

Denying medical care to inmates was not what David Selvage signed up for when he took a job at the corrections department, as Health Services Administrator, in October 2017. He spent much of his earlier career working for the state Department of Health including several years in rural, medically underserved areas of the state, and he says he came to the corrections department in the hope of making a difference for a particularly vulnerable population. But he acknowledges that when it comes to hepatitis C, they are failing to meet the needs of all sick prisoners. “The problem exists: we recognize it.”

He said the eligibility criteria are a means of rationing scarce healthcare dollars. “We simply don’t have enough funding to treat everybody who needs to be treated at the time of infection.”

The corrections department does not even manage to treat all the patients it designates as “Priority 1” due to the gravity of their illness. And data from the last three fiscal years offers little evidence of meaningful efforts to expand access: as the market price of hepatitis C drugs fell during that period, rather than expanding access to more people, the corrections department cut spending on the drugs by 72 percent.

Selvage said for the coming fiscal year his goal is to triple the number of people treated, at a cost of $2.5 million. But by his estimate, the department would need $50 million of medications to treat all infected people in their custody — a thirty-fold increase in spending over 2018, more than their entire annual healthcare budget. And that doesn’t reflect additional hires needed to manage thousands of new patients. He also argued that the department should upgrade from its archaic, paper-based health record system to an electronic one that allows for far more detailed tracking of cases, at a cost of $3 to $5 million.

Without new resources, the corrections department will continue to pass the buck, leaving prisoners to seek care on their release from outside clinicians. This, at least, it does commendably, by pre-enrolling inmates in Medicaid so they are insured as soon as they are freed. And it’s how Serna finally got treated: on his departure from the penitentiary, an acquaintance put him in touch with a nurse, Debra Lockey, who gave him an appointment that same day.

Lockey has focused on managing hepatitis C patients for a decade, at one point administering treatment to indigent patients referred by a network of eight federally qualified health centers. She estimated she had been involved in the treatment of 800 to 1,000 people, of whom 30 percent had been previously incarcerated. Although the onset of liver damage varies, she’s witnessed firsthand the consequences for patients who had to delay treatment even a few years. “Some people can live 50 years with this virus and never develop cirrhosis or liver cancer, but some can have it for a short period of time and develop these illnesses. It is in the best interest of anybody with hepatitis C to be treated as soon as possible.”

She is happy to see people immediately upon their return from prison but the tumultuous period of reentry can be a risky time to start a course of treatment that demands regularity to successfully eliminate the virus. In several instances, Lockey began treating patients who were then re-arrested, interrupting their therapy midway and threatening to foster drug-resistance. “I would actually get their medication delivered to the clinic and then make the drive out to the jail to give them to the nurse there to see if they could continue the treatment,” she recalled. One such client successfully completed therapy, but two were unable to do so.

Most troubling to Lockey was the message these obstacles sent to her patients, who seemed to absorb the lesson that they simply didn’t deserve treatment. She recalled many conversations “getting them to understand they are worth every penny, and they are worth me spending the time on their prior authorizations and fighting and going to court.”

Courts jump into hepatitis C treatment in prisons

But change may be coming, from the courts.

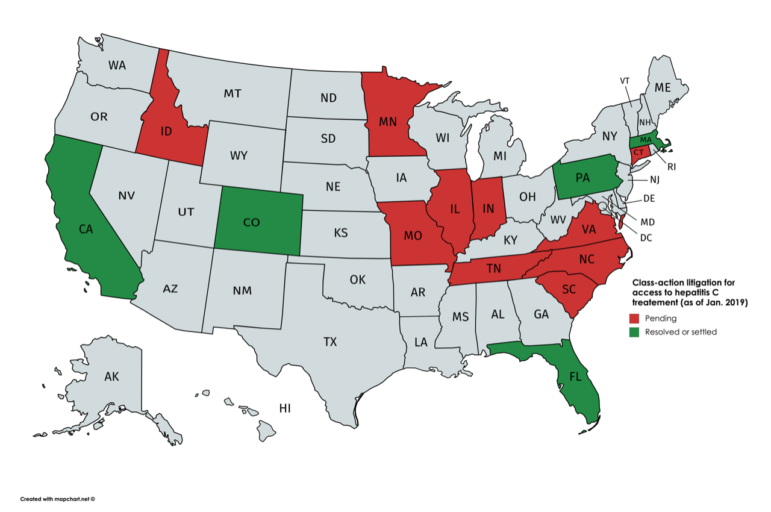

Since 2015, prisoners in at least 16 states have introduced class-action lawsuits asserting a right to access the new therapies. The Eighth Amendment forbids cruel and unusual punishment, which has been interpreted to mean that states cannot show “deliberate indifference” to the serious medical needs of their prisoners — including by withholding treatment solely as a matter of cost. And as universal treatment for hepatitis C has become the standard of care for people in the outside community, withholding it from those who are locked up looks increasingly untenable.

In the first major ruling on the matter in November 2017, a federal judge in Floridaordered the state to accelerate prisoners’ access to treatment, at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars. Soon after, Colorado settled a lawsuit and agreed to allocate $41 million in new funding to treat all people with hepatitis C currently under its custody, andMassachusetts and Pennsylvania quickly followed. A handful of governors, including New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo and Governor Jay Inslee in Washington State, have preempted litigation by committing to provide universal treatment in their prisons as part of strategies for eliminating hepatitis C statewide.

Civil rights advocates in New Mexico are aware of these trends. Frances Carpenter, a private attorney who has represented incarcerated people in other cases over the years, said that she was struck by her clients’ descriptions of the corrections department’s narrow criteria for treatment access. “Their parameters are just completely arbitrary,” she said.

Recently she met with the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which has filed public records requests seeking information about the state’s treatment practices, according to its legal director Leon Howard. The team say they are watching the actions of Democratic Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham carefully, and should she fail to act, litigation is a real possibility. Last week, Lujan Grisham named Julie Jones, who oversaw Florida’s prisons, to lead New Mexico Department of Corrections.

Randall Berg, an attorney who represented the sick inmates in Florida, thinks that conditions in New Mexico are ripe for a lawsuit. Judging by the tiny fraction of New Mexico inmates who are receiving treatment, he wrote in an email, “I believe one can safely say the New Mexico Department of Corrections is being deliberately indifferent to the serious medical needs of its prisoners.”

State legislators and committee staff said that under the Martinez administration, the corrections department had been tight-lipped, which might explain why they seemed sanguine about it. “In regards to the hepatitis C issue, I think we’re in pretty good shape on that,” said State Senator John Arthur Smith, who chairs the influential Senate Finance Committee. “I’ve heard no rumblings that people think they’re not being served appropriately.”

Governor Lujan Grisham’s staff signaled she might be more proactive in addressing the problem. “The numbers are jarring,” said her communications director Tripp Stelnicki after reviewing data on the dearth of treatment. He indicated the governor would lead rather than follow: “She has no interest in letting this play out in the courts, rather than addressing behavioral health needs in our prison system. And on top of that, it’s just responsible from a moral and fiscal perspective.”

“We simply don’t have enough funding to treat everybody who needs to be treated at the time of infection.”David Selvage, Health Services Administrator with the Department of Corrections.

***

But another policy also jeopardizes the state’s response to hepatitis C, one that has little to do with expense and everything to do with stigma towards injection drug use. That’s the primary route of transmission of hepatitis C in New Mexico: in a 2018 health department report, 56 percent of people under 30 who were newly infected said they had injected drugs. (One of the reasons the prevalence of hepatitis C in prisons is so high is because the criminal justice system concentrates people with drug addictions there.)

While a court’s decision could expand treatment to the pool of sick inmates already in the state’s custody, the cures for hepatitis C do not confer immunity against reinfection, so tens of thousands of dollars of drugs and months of delicate care can be squandered, in an instant, if a patient is re-exposed.

Advocates say that to effectively address the epidemic, policymakers need to allow prisoners with opiate addictions to receive medication-assisted treatment to help them reduce their drug use and slow spread of the disease. But at present, when it comes to addressing addiction, the state prisons offer an environment that does much more harm than good.

Medication-assisted therapies

Snow was falling outside the church in Los Alamos where Fernando Trujillo was at work cleaning the carpets. His slight frame was enveloped in a set of oversized shirt and pants, and a pair of rimless glasses perched on his high cheekbones. The 27-year-old had been hired for the custodial job by his dad’s business, and he was living in his mom’s house down the hill in Española, where he grew up in the epicenter of northern New Mexico’s opiate epidemic.

And that’s crucial to his story, he said. “I think for you to understand hep C, you have to understand the addiction, too. Why else do we have hep C, the majority of us? It’s because of our addiction.”

Trujillo said he was introduced to prescription drugs at 13, and when he was 16 he tried heroin. Between run-ins with the juvenile justice system he managed to graduate from high school, but he couldn’t shake his addiction and in 2011 he was diagnosed with hepatitis C. “I felt like I had cancer or something,” he said, adding, “I never thought I would get rid of it.”

Thus began a cycle in which charges for drug possession were invariably followed by new arrests. Trujillo might be released on the condition that he quit using drugs, but would then relapse and fail a mandated urine analysis. At one point he managed to stay clean, but his boyfriend — “my high school sweetheart, my Bonnie and Clyde” — was using and overdosed, and Trujillo fell off the wagon again. Of the last six years, he figures he spent more time locked up than on the streets.

Trujillo accepts personal responsibility for his actions, he says, but in crucial ways the criminal justice system made it harder for him to quit using. For one thing, he says heroin is more freely available in prison than it is outside: “The state system, it’s like a party.” He’s convinced that if he gets locked up again he will relapse.

To stay sober, he also depends on a daily dose of buprenorphine/naloxone (known better by its brand name Suboxone), which binds to chemical receptors to reduce physiological cravings. In combination with other behavioral therapies, this type of medication-assisted treatment has been shown to help people surmount their addictions and cut risk of a fatal overdose by as much as half.

Yet New Mexico’s state prisons bar inmates from obtaining this medication while they are locked up, even if they had a doctor’s prescription for it at the time of their arrest.

This is wrong-headed, says state District Judge Jason Lidyard, who was appointed last year by Gov. Susana Martinez and operates a drug court in which Trujillo now participates. “With respect to how the criminal justice system deals with drug addiction, it’s very insensitive to it.” Lidyard was 21 when he lost his own father to a drug overdose, and while he condemns the addiction that led to it, he considers it a blessing that the criminal justice system never deprived his father of his liberty while he struggled with it, which would have jeopardized the stability of their family.

Limiting access to medication-assisted therapy may also be unconstitutional and a violation of the American with Disabilities Act.

Last fall when a Massachusetts jail refused to give a prisoner access to the medication-assisted treatment he had been prescribed on the outside, a federal judge issued an injunction. Sally Friedman, a vice president at the Legal Action Center, a national group that advocates for sound public policies towards addiction, called the decision “groundbreaking” in an email, and wrote that “corrections officials nationwide should expect to see more litigation like [it].” Lawsuits are already underway in Maine and Washington State.

“I think for you to understand hep C, you have to understand the addiction, too. Why else do we have hep C, the majority of us? It’s because of our addiction.”Fernando Trujillo

New Mexico’s state prisons have a local model to look to: Albuquerque’s Metropolitan Detention Center. Beginning in 2005, the Bernalillo County-operated jail has allowed detainees with prescriptions for methadone to fill them, and it started initiating the therapy for other detainees who needed it.

Governor Lujan Grisham is no stranger to the jail’s program: she helped start it, as then-state health secretary. “It’s a legal treatment aimed at solving the problem and stopping the revolving door,” she said at a press conference after its opening in 2006.

Reforming the way New Mexico treats addiction could help it address hepatitis C, too. In a cohort of young adult injection drug users, those on medication-assisted treatments like Trujillo were 60 percent less likely to acquire the virus.

And Trujillo’s experience suggests that addressing their hepatitis C could also help them beat their addiction. Since his release last March, he said he has fought to stay clean like never before. Although he relapsed once, for the first time he took the initiative to seek help himself. “Maybe I needed it. Maybe I needed to see what my life was going to be like, and what it could be like.”

Getting treated for hepatitis C helped steel his resolve. The infection felt like a shadow cast by his prior drug use that was still clinging to him; eliminating it gave him the sense he was finally freed from that phase of his life. “When [the nurse] told me that I didn’t have hep C no more, I cried,” he said, his eyes welling up at the recollection. “That gives me just another reason not to relapse, not to backtrack, not to mess up.”

Ted Alcorn is a writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The Lancet. He lives in New York City and was raised in New Mexico.