By Ted Alcorn/ New Mexico In Depth

Alcohol is killing New Mexicans at a higher rate than anywhere else in the country — yet the state has largely neglected the growing crisis. In this seven-part series from News Port partner New Mexico In Depth, journalist Ted Alcorn investigates the state’s blind spots and shines a light on solutions.

Alcohol dependence is New Mexico’s biggest untreated substance use problem. Doctors can do more to treat it.

By 2013, Steve Harbin’s alcohol problem was plain to nearly everyone.

Once a prosperous salesman in the construction industry, he’d lost his job and health insurance. Gone were the dream house he’d designed in Albuquerque’s foothills and many of the motorcycles he’d owned. The last one, a Kawasaki W650 with a peashooter exhaust, sat in his garage in disrepair.

His marriage had been disintegrating for years and now the stepdaughters he’d helped raise despised him, the way Steve hated his own dad who he’d sworn to never become.

He was draining two bottles of Irish whiskey a day. More of his social security check went to booze than anything else.

But the person with whom Steve spoke most openly about his drinking and should have helped him cut back was the last to notice the problem: his doctor. The clinician had known Steve for decades, but never diagnosed his drinking disorder nor referred him for treatment. He was quick to shrug off his patient’s risky behaviors, as Steve recalled it, content to leave the patient to help himself.

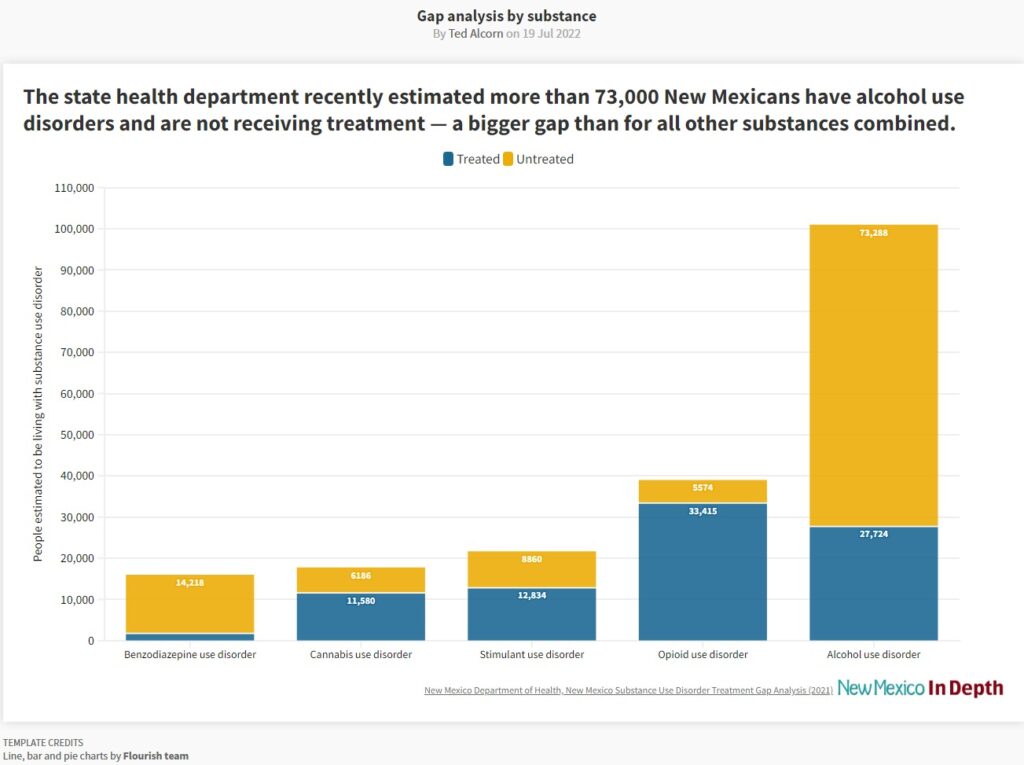

Steve’s plight was stark but not uncommon. According to the New Mexico Department of Health, over 73,000 residents who could benefit from treatment to reduce their alcohol consumption are not getting it, more than people addicted to all other substances combined.

State officials, physicians, and patients offer varied explanations for this gap. Treating alcohol dependence is not easy: addressing it means changing lifelong habits. Plus, New Mexico has too few psychiatrists, behavioral health providers, and social workers, and only a handful of doctors specialize in addiction medicine. The state’s poverty aggravates the challenge.

But problem drinking also often goes unrecognized. The latest survey data show that of New Mexicans who had a drink in the previous month, more one in four meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder, among the highest proportions in the country.

And again and again, clinicians and even patients lay responsibility on the person with the addiction. “I firmly believe that unless someone wants to make the change them self,” Steve said, “they’re not going to quit.

William Miller, a professor emeritus at UNM and one of the world’s foremost experts on the psychology of change, respectfully disagrees. “Waiting for people to ‘hit bottom’ is a pernicious myth,” he wrote in an email.

Working with problem drinkers in New Mexico nearly 40 years ago, Miller and colleagues developed ‘motivational interviewing’ — a form of counseling that helps patients change their drinking habits by exploring and resolving their own ambivalence — that is now applied around the world.

It’s unethical for doctors to delay treatment for patients with asthma, diabetes, or heart disease until they are sufficiently motivated, and Miller said alcohol disorders should be no different. “Helping people find their own motivation for change is an important and early part of our job, and there is solid science that it’s possible.”

Missed opportunities

Steve’s drinking was rooted in his fraught relationship with his own father, low self-esteem, and depression, but he was better off than many New Mexicans in similar straits. He was professionally successful.

His wife Angie was committed to the soft-spoken man who had charmed her and fallen in love with her girls. Originally from the Midwest, she was raised to believe if you work hard enough, you will succeed. She looked at her relationship with Steve that way.

“I’m a person that doesn’t throw in the towel very easily,” she said. “You see it out till you see that you have nothing left to give.”

More than a decade into their marriage, she’d pushed Steve to enter treatment, moving in with her sister until he agreed to enroll in a multi-week program at Presbyterian’s Kaseman Hospital. But Steve thought the sessions were awful. “It was more of a shaming process than it was anything positive about it.”

He stopped drinking, Angie recalled, but, like clockwork, fell off the wagon every six weeks. “The problem was he never did the work so he never really did understand what was going on,” she said. “It was just a white-knuckle flight.”

The health system could have done more to meet him where he was at.

Steve had been seeing the same primary care doctor for over 20 years, a man in private practice around his age. When Steve lost his health insurance, the doctor retained him as a patient.

“He was really one of the most caring doctors I’ve ever known.”

They often spoke about Steve’s drinking and the harmful effects of alcohol on mental and physical health, Steve said. But when Steve struggled with debilitating anxiety about work, the doctor prescribed a benzodiazepine, a class of drug that can be addictive and dangerous to mix with alcohol. Steve became dependent on that, too.

“He would keep prescribing them for me and he would just say, ‘you’re not drinking too much while you’re taking these.’”

Steve’s plight wasn’t unusual, recent research shows. Seventy percent of people with alcohol disorders report a doctor asking them about drinking in the last year. But only 12% say they were counseled to cut down, and just 5% say the doctor offered information about treatment. That simple approach — what is called Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment, or SBIRT for short — is effective at reducing alcohol consumption among heavy drinkers, studies show.

For decades, Steve’s doctor missed the seriousness of his drinking problems, he said, and never recommended anywhere to seek help. “He told me one time that ‘I don’t really think you’re an alcoholic,’ and that always made me feel odd — because in the long-run, I was an alcoholic.”

That sort of thinking — of good and bad drinkers — can also be a blind spot.

It’s appealing to believe doctors can sort drinkers into those unable to control their habit and those who can, Miller said, but the science of addiction has moved away from that dichotomy. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association did away with categorical distinctions of alcohol ‘abuse’ and ‘dependence’, replacing them with a spectrum from mild to severe disorder. This recognizes that patients like Steve exist on a continuum and, wherever they are along it, can benefit from interventions meant to reduce alcohol consumption, even without necessarily eliminating it.

And primary care doctors who identify an alcohol disorder often push patients towards specialists and inpatient care, in spite of evidence they can help immediately.

A landmark trial found patients who were counseled by their doctors and prescribed naltrexone, a medication used to treat opiate disorders that has also been shown to reduce many patients’ cravings for alcohol, fared as well as patients receiving more intensive counseling from specialists. “That’s one of the big misconceptions I see in the field,” said Dr. Snehal Bhatt, the chief of addiction psychiatry at UNM.

Bhatt said referrals are especially ill-suited to New Mexico, where many treatment providers lack enough trained staff or are limited by the capacity of their facilities and can’t easily accommodate new patients. “They wind up shuttling back and forth, just waiting around, and they’re getting increasingly desperate,” he said. “That’s frustrating, because we can be doing something right now.”

The mantra of Bhatt and others, who are trying to make counseling available to patients wherever they seek care, is every door is the right door.

A rollercoaster ride

In his late 50s, Steve was drinking upon waking to numb hangovers and didn’t stop until he passed out. Years earlier, Angie was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, and now stress caused the disease to flare up. Steve coped by drinking more.

He was at his best on visits with his grandkids, his youngest step-daughter Meredith Boles recalled, when she saw a glimmer of the person who had helped raise her. “At one point he was this lovely man, and I remember bits and pieces of him,” she said. “And he just slowly became this thing.”

Meredith saw her stepfather’s behavior as increasingly delusional. He’d bought a gun and once left it on the bed for her mom to discover it, she recalled. On multiple occasions he called Meredith’s sister, telling her he was contemplating suicide, keeping her on the phone for hours as she talked him out of it.

Meredith put some distance between her family and Steve, moving to Colorado in 2010. “I didn’t know how to help him other than to set boundaries for us,” she said. Angie followed, filing for divorce.

What finally saved Steve was a lucky accident. He stumbled on the number of a little-known substance use clinic that the psychology department of the University of New Mexico (UNM) runs out of a tiny on-campus residence, and left a message. Weeks later when a graduate student called him back, Steve recalled, “I had trouble trying to figure out who the heck it was.” But the clinic offered state-of-the-art treatment and his lack of health insurance was no obstacle: they charged him one dollar per session.

His progress took years — “a real rollercoaster ride,” he called it — but with the counselors he finally began to unpack the root causes of his drinking and to treat an underlying depression. The clinic eventually referred him to UNM’s Addiction and Substance Abuse Program (ASAP), where his treatment continued and clinicians prescribed him naltrexone. Numerous studies have found it assists motivated patients reduce their drinking, although the most convenient, injectable version can be costly even for those with insurance.

“It’s life-changing,” said Steve. “I just never think about drinking, which is incredible for me.”

Despite its effectiveness, naltrexone is underused: nationwide, just 1.6% of people with alcohol disorders have received medication for them. And in New Mexico, of more than 100,000 people with any type of substance use disorder, fewer than 4,000 people have a prescription, according to the Legislative Finance Committee.

Steve has been sober more than a year and a half, the longest period in his adult life he has gone without a drink.

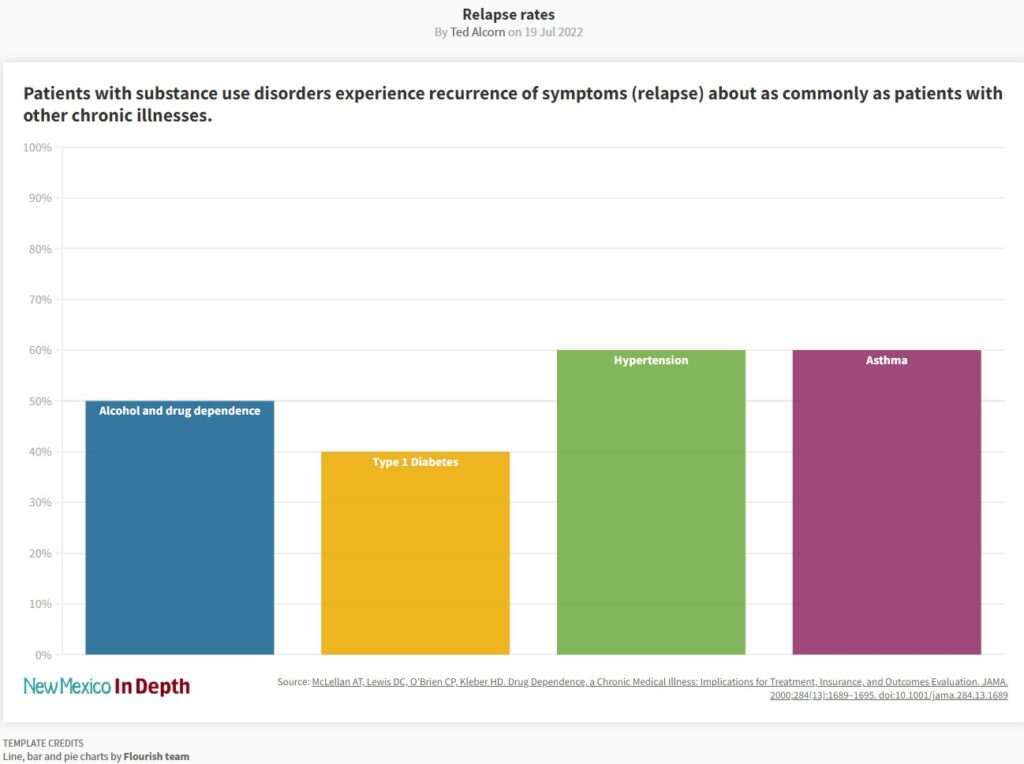

His success is not an aberration: identified early and treated according to best practices, people with addictions respond better to treatment and experience less frequent recurrence of symptoms (in their case, relapse into substance use) than those managing high blood pressure or asthma, studies show. “If you have to have a chronic illness, addiction is not a bad one,” Miller said. “Most people do get far better over the course of treatment.”

Most patients at ASAP are self-referred, and it surprised Steve the program wasn’t more widely known. “The medical community doesn’t seem to be aware of the resources,” said Steve. “A whole lot of medical people that are in the UNM system [don’t know about it], which is really crazy.”

New Mexico’s medical community could do more to change this. In 2004, with funding from the state health department and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the New Mexico Medical Society created a handbook for the state’s physicians about screening and counseling patients on problem drinking. But the organization ceased distributing it in 2010 when the grants ran out and has not done further alcohol education since.

The Greater Albuquerque Medical Association has never offered any educational programs about counseling patients with alcohol disorders or prescribing them medications, according to executive director Sylvia Lyon. UNM Hospital is working to make screening for alcohol disorders and brief counseling interventions available to every patient who seeks primary care, the gold-standard for decades, but that goal is still a few years away.

State Medicaid director Nicole Comeaux said her office is considering changes to encourage more providers to screen, intervene and refer to treatment individuals struggling with alcohol disorders. Nearly half of New Mexico’s population is insured by Medicaid — which covers people who are low-income or disabled, among others — so the program wields outsize influence through the policies it sets for managed care providers.

Since 2019, clinicians can bill for time spent conducting SBIRT, which is more cost-effective than other types of services for alcohol disorder such as intensive outpatient treatment. But the state’s providers only billed for 8,000 sessions in 2020, which the Legislative Finance Committee calculated to be 1% of the overall Medicaid population. “Those numbers are much lower than I would like to see,” Comeaux conceded.

The failure to counsel even a single patient who needs it can have far-reaching consequences. Steve’s alcohol disorder hurt the people around him: years after their divorce, Angie said she still has difficulty trusting people and will never remarry. “The focus is usually on the person that is suffering with the addiction, but the ripple effect is so broad, down to not only spouses and mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters, but the next generation.”

Indeed, Steve’s relationships with his step-daughters and his grandchildren seem beyond repair. In Al-Anon, the support group for families of people struggling with alcohol, they advise to detach with love, but by the end, Meredith said she felt total indifference. “I just don’t see him as that person that I did love. The person that I did love…I can hold a different space for that person.”

Nowadays Steve’s life is stable and quiet. He doesn’t have many friends and age is slowing him down. But he takes satisfaction from cleaning his front yard and restoring an old camping trailer. He’s got a 20-pound mutt to take care of, too.

And having cleaned the carburetor of his Kawasaki motorcycle and recharged the battery, once or twice a month he will go on a ride. Years ago, he liked looping north on NM-14 behind the Sandias to Pojoaque, stopping in Jemez Springs to see a friend before completing the four-hour loop.

Now he mostly takes the bike to sessions at the clinic.

“I don’t know what it’s like for other people but when I’m riding a motorcycle, I don’t think of anything else,” he said. “It’s kind of a mindfulness exercise. It wipes my mind clean.”

Ted Alcorn is a writer raised in New Mexico whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The Washington Post Magazine, among other publications. For New Mexico In Depth he’s investigated how the state’s prisons have ignored an epidemic of hepatitis C, how Albuquerque stood up its branch of non-police emergency response, and how non-profit hospitals shortchange community health. Follow him at @tedalcorn.

This story was originally published by New Mexico In Depth