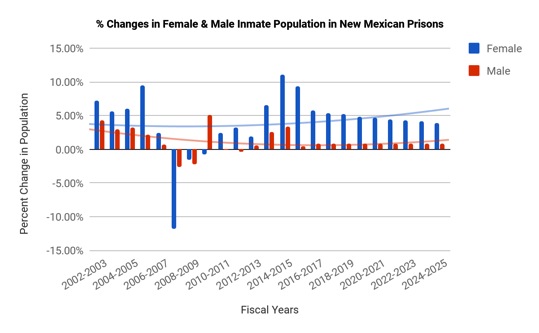

As news breaks of New Mexico prisons nearing capacity, data show a strikingly high rate of growth in female incarceration rates. The New Mexico Sentencing Commission presented its 2017 Prison Population Forecast to the Legislative Courts, Corrections and Justice Committee in early September. The commission’s report reveals that between the fiscal years 2012 and 2016, the number of female inmates in state prisons has increased by more than 22 percent, while the number of male inmates has increased by only 9 percent.

One expert on incarceration rates in the United States says the reason behind the rapid rate of women going to prison may be the system itself.

“One of the biggest problems with prison systems is that it is designed for men, so women are more likely to fail at the system,” says Chris Hartney, Senior Researcher at the National Council on Crime & Delinquency (NCCD). “Anything that fails to help you facilitate your success in the community is going to be a contributor to rising rates.”

“I feel like they didn’t care. I feel like they were just trying to put us in jail,” said Katherine Madarno, 34, who was incarcerated.

“That’s why I stopped caring about the system. I was just like ‘Whatever. Throw me in jail. Send me to prison. Send me to rehab. I don’t care!’ Because I felt like they didn’t care, so why should I?”

Madarno frequently attends meetings by Wings for LIFE International, an Albuquerque-based organization that addresses the cycle of incarceration and its affects on New Mexican families.

“The system focuses more on incarceration as opposed to rehabilitation,” said Sophia Romero, 36, also an ex-inmate and frequent attender of Wings for LIFE meetings.

Hartney says, in general, women are incarcerated for less serious crimes than men. Women were more likely than men to be incarcerated for drug-related offenses (25% vs. 15%), as well as for property offenses (28% vs. 18%). In 2014, over 50% of male inmates were convicted for violent crimes, and of women inmates only 36%. But even for violent crimes, the data is not transparent. ‘Violent crime’ has become an umbrella term that applies to all cases of violent offenses and assaults, despite the degree of severity. “It is more common that a woman in prison for a violent crime is there for a lesser crime than the men that are in prison for violent crimes,” says Hartney.

Most of the trends in rising incarceration involve increased prosecution of lower-level crimes over the years. For instance, in the case of domestic violence, law enforcement practices have changed significantly. Unlike domestic disputes in the past, it is more common nowadays for law enforcement to arrest both parties involved regardless of the situation. A party can get booked on an assault charge, whether it be a verbal assault or a threat of violence rather than an actual violent crime. Nevertheless, any assault is a violent crime and therefore that individual will be prosecuted.

“That’s one way that both the women involved in the domestic violence and the young girls end up getting system involved, for potentially so-called violent crimes, but it is not a change in behavior. It is the same thing that used to happen, except law enforcement is handling it differently.”

Between fiscal years 2017 and 2025, women incarceration rates are expected to increase by 44% for the total population of female inmates.