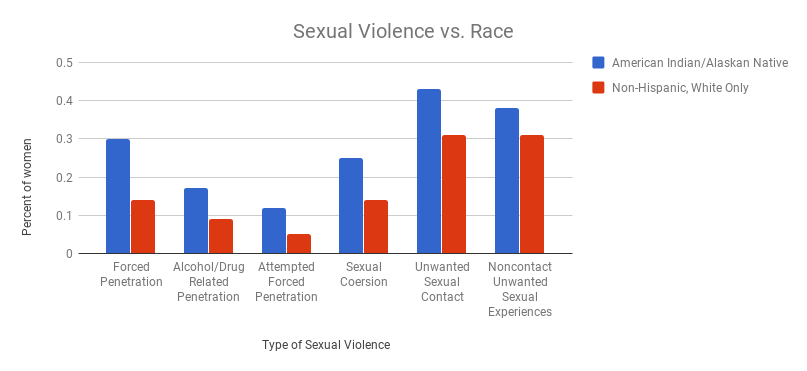

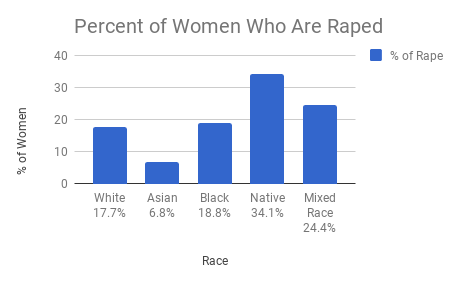

The #MeToo movement has given women the platform they need to tell their stories, but some women in the Native American community are still apprehensive to speak out. Studies show Native American women are twice as likely to experience sexual violence in their lifetime compared white women to their white counterparts.

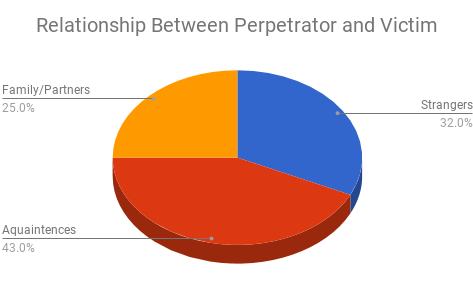

Anthony Tillman, Vice President of the National Native American Human Resources Association, said sexual violence is hardly reported by native women because a lot of the violence is committed by close family or important community members.

“It happens interfamily,” Tillman said. “It’s their uncles… (or) the pillar of the community that does so much, but has these secrets. You don’t want to be the one to bring that person down. (People think), ‘Nobody is gonna believe me.’ It’s a lot of pressure to come forward.”

According to research conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 68% of Native women were raped by intimate partners, family members, or acquaintances. The other 32% of rapes were committed by strangers.

Renee Lowden, a Native American woman who works as career tech training manager at Albuquerque Job Corps, said the fear of speaking out runs deep.

“I think sometimes what happens on the reservation is women think, ‘If I report this sexual abuse, is my family gonna back me and if they don’t back me, where am I going?’,” Lowden said.

According to a 2016 research report conducted by the National Institute of Justice and written by Andre B. Rosay, Ph.D., more than 4 in 5 American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime, that is 84%.. And 56% percent said they experienced sexual violence.

Rachael Lorenzo, Communications and Outreach Coordinator for Native Community Development Associates — a woman-owned company that promotes Native communities — aids survivors of sexual violence, but said she can only help if the women decide to speak up.

“NCDA have such an important role to play from the time a call is made to report an assault, if a call is even made, because not all assaults are reported, especially for native people,” she said. “A police officer visits the home, and usually a social worker will accompany the officer.”

Lorenzo said the police officers and social workers strive to create an environment for survivors in which they feel safe enough to report these incidents. Despite the efforts, some victims are still hesitant to ask for help.

Tillman said women are also afraid to speak up because if they do, they can be ostracized from their community. This can lead to being fired as well as a tarnished reputation, making it hard to maintain a household and find a new job.

“Women learn to keep their mouth quiet about it,” Tillman said.

But, Tillman said, communities need to encourage women to speak up and not fear the retaliation.

“I think you always have to make an example of somebody in order to make the movement strong,” he said. “You have to find someone who is willing to accept the consequences of coming forward.”

Tillman said the encouragement and confidence to speak up starts in the home. Before children are introduced to the opinions of the community, parents should be instilling a sense of morality in their kids. He said just because the community has thought one way for so long, doesn’t mean it’s right. Wrong is wrong.

Tillman said parents need to break the cycle, especially, “if parents have been part of the abuse and they haven’t said anything, the kids see that and they feel like they better not say anything.”

Lowden said sexual violence is not talked about or reported because people have learned to keep it hidden because that’s the norm.

“Another thing that happens is we’re dealing with the daughters of the mother,” Lowden said. “Because we’re dealing with the daughters of the mothers who have been sexually assaulted or sexually abused, it could be that they didn’t have the resources themselves, and so they don’t know how to handle their daughters and their issues and because of that they don’t know how to refer them.”

But Tillman said tribes have begun to better equip themselves with the tools they need to handle these kinds of situations.

“Managers and supervisors came to me,” he said. “They asked, ‘hey, what can we do? Are people trained? Do our people even know what it looks like? Have we been properly equipped to even identify what sexual harassment or sexual misconduct is?’”

Tillman said NNAHRA holds summits with different tribal nations across the country to discuss and address the problems natives are facing. Tillman said he hopes that with proper training, tribes will learn to better deal with sexual harassment and violence, which in turn will lead to people speaking up when there’s a problem.

But, Tillman said, the policies don’t matter if they’re not met with support.

“We want our women to understand they have a safe place,” he said.

Felecia Pohl and Autumn Scott can be contacted on Twitter @FeleciaPohl and @autumnsagekingg.