New Mexico’s future: To better understand the challenges and circumstances our children face, Searchlight New Mexico is spending a year visiting and profiling kids from every corner of the state.

In this home, the Navajo language unlocks tradition and identity

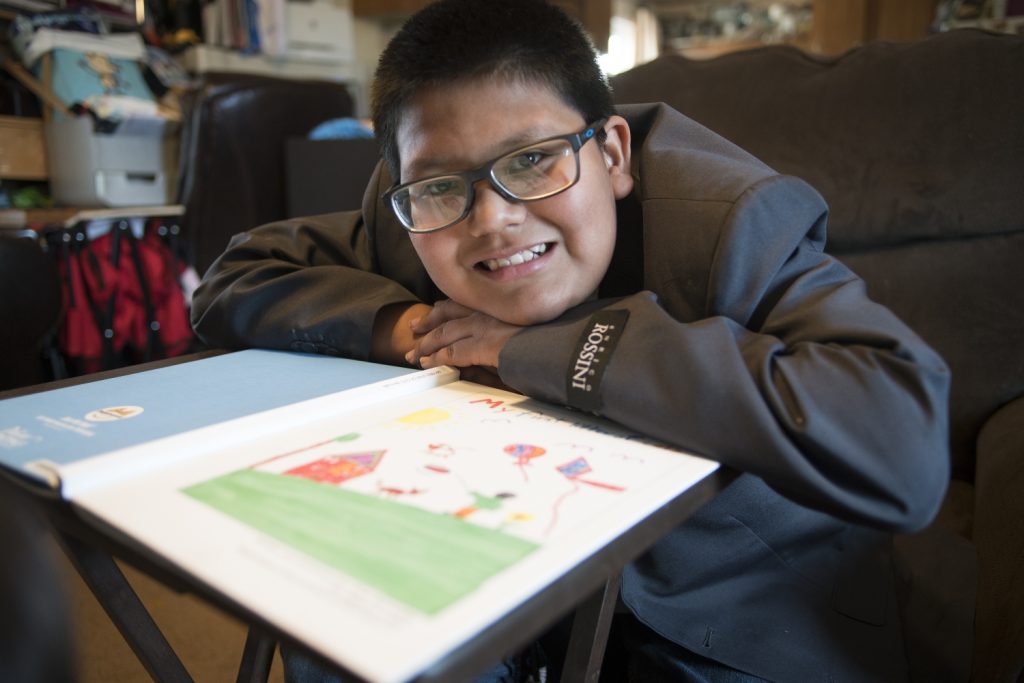

Tyler Bennallie, 11, sprawls on the floor of his family’s mobile home on the Navajo Nation in Fort Defiance, Arizona, while his baby sister bounces on his back. He doesn’t mind when 1-year-old Emily plays horsey on him, or when she babbles loudly in his ear, or when she interrupts his efforts to talk about his favorite things, like Iron Man Legos.

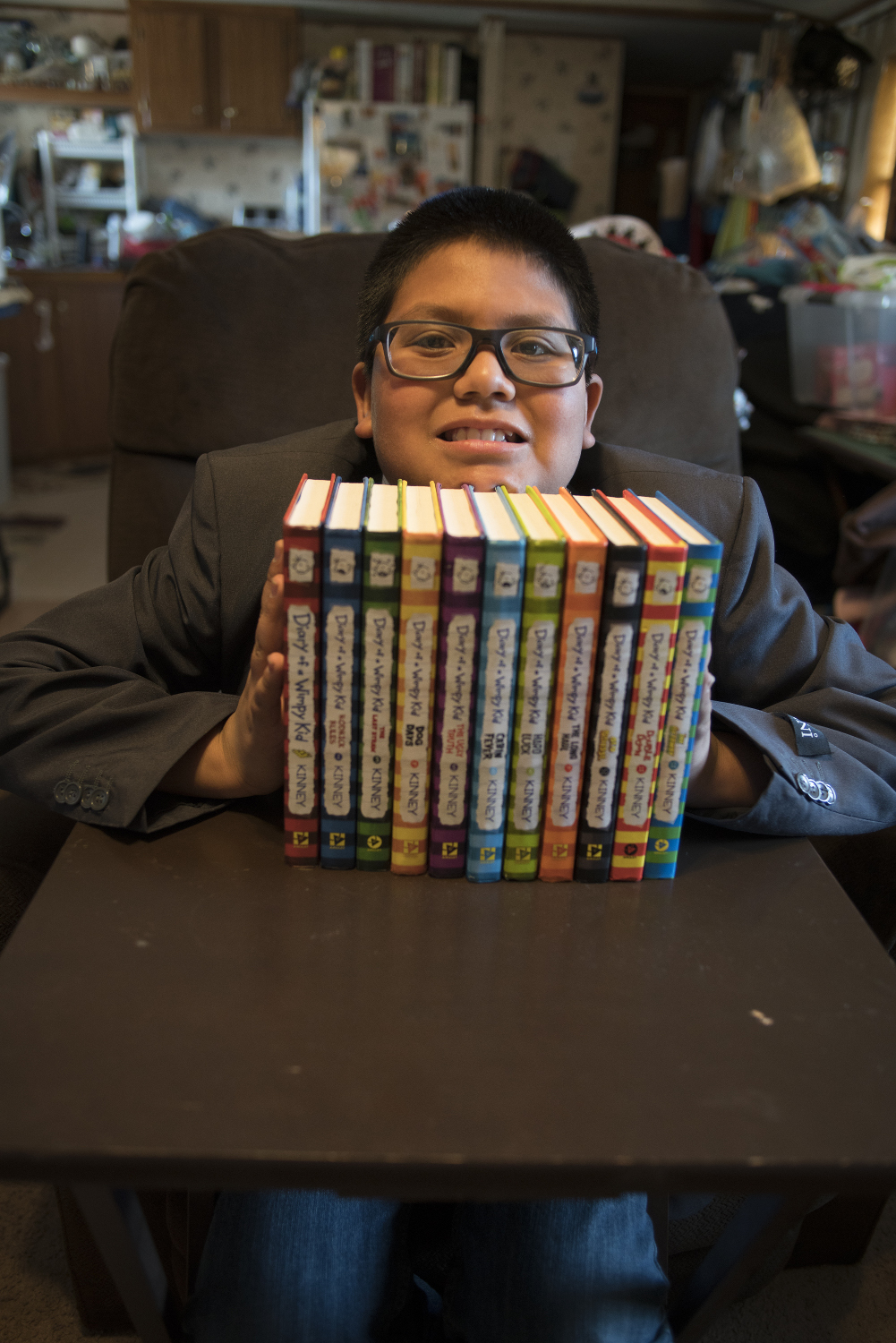

A tall, kind-faced boy with dark-framed glasses and a buzz cut, Tyler doesn’t even object when Emily grabs his prized “Diary of a Wimpy Kid” books. His brothers, Conner, 4, and Bryson, 6, meanwhile play with his Lego Super Heroes — his most treasured possessions — which could be headless, legless or MIA by the time the two get done. “They usually destroy all my stuff,” Tyler says calmly.

He lives with his family on the Navajo Nation, a 27,000-square-mile expanse of high plains and desert in New Mexico, Utah and Arizona, a region the size of West Virginia. Many of the Diné (“the people,” in Navajo) live in remote communities separated by miles of desolate country. Families grow up in hogans and homes without running water, electricity or plumbing. The closest grocery store might be 40 miles away.

The Bennallie home is urban by comparison. The family resides a few miles north of Window Rock, the capital of the Navajo Nation, where there’s a shopping center, cinema, museum, government offices, small zoo and a memorial to the Navajo Code Talkers, who used their language to transmit military messages to the Allies and thus played a pivotal role in winning World War II.

The family’s single-wide trailer is a cheerful clutter of toys, photos, plastic bins, science projects, craft supplies, clothes, tables, chairs and couches, arranged as neatly as possible. It is home to the four children and their stay-at-home mother, Amanda; father, Evans (an IT manager for the Navajo Nation Division of Transportation); and grandmother Mary Lou Tsosie, an account clerk at the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority.

Mary Lou gets the master bedroom; the six Bennallies share two small bedrooms. And there’s always space for Valerie Tsosie, Amanda’s older sister, who drops by to take care of the kids and “get my family time,” as she puts it.

Family is everything. “Our parents lived on a dirt floor without running water or electricity,” Valerie says. “We didn’t think twice about it. Later on, when people told me I was poor, I said, ‘Oh, I was?’”

Valerie joined the military “the minute I turned 18” and lived in Paris and New York before realizing she needed to return home: “I didn’t want to be the outsider anymore.”

Amanda helped her find her footing. “She reeled me in,” Valerie says.

Some of their family members have been impacted by substance abuse, as have so many people on the Navajo Nation. But Amanda doesn’t necessarily blame poverty. She attributes the problem to a lack of foundation, her word for tradition. Without tradition as a foundation, she says, people get lost.

She wears traditional clothes — a skirt, moccasins and jewelry to honor the culture and protect her from bad fortune.

“It’s a way of life, it’s who we are, it’s how you stay positive, it’s how you move forward,” Amanda says.

Tyler and Bryson attend a Navajo language immersion school, where the weekly calendar includes traditional dress days like “kélchí (moccasin) Monday” and “tsiiyéél (hair bun) Tuesday.”

Students unintentionally practice what’s commonly called “walking in two worlds.” They play the ancient Navajo stick game at the Tsé Hootsooí Diné Bi’ school. But they also play “Angry Birds” on their smartphones. They learn about Diné core values, including balance, wellness and kinship. But if they’re like Tyler, they’re also thinking about robots, supercomputers and megaflops.

The immersion school teaches in Navajo until third grade, then students switch to English to prepare for them for required standardized tests. The toggling can be hard.

Valerie says Tyler chafes sometimes when she makes him say “Bad Piggies” in Diné before letting him play the game. He seems to feel more comfortable with English, but struggles with things like spelling bees.

“I don’t even know how to spell burrito,” he laments.

Amanda understands, but she believes fiercely that traditional ways of life and culture hinge on keeping the language alive. She speaks it fluently, as does her sister and mother.

Tyler’s own fluency — and his ability to say “Sandy Plankton” in Diné — are the main reasons he won a speaking role in the Navajo version of the blockbuster “Finding Nemo,” in 2015. He was in third grade when he was chosen for the part of Tad, the bullying butterflyfish who goads Nemo into swimming out into the open sea.

“What were the lines I had to say?” he asks his mother recently. He is not impressed with his own stardom and only talks about the movie when prodded.

“The line I remember most is, ‘I’m obnoxious,’” his mother says, laughing. “There’s no word in Navajo for ‘obnoxious,’ so they translated it into a word that means ‘I’m ugly’ or ‘I’m trash’ or that kind of thing.”

“Finding Nemo” (“Nemo Hádéést’į́į́”) was only the second Hollywood film dubbed in a Native language, the first being the 1977 “Star Wars” movie, which debuted in Navajo in 2013. Pixar-Disney made both features in collaboration with the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, aiming to inspire young people to learn what many fear is a dying language.

Mastering it is no easy feat. Navajo was chosen as the Code Talkers’ language precisely because it’s one of the most difficult in the world.

![]()

What’s remarkable, linguists say, is that Navajo — or Diné Bizaad — has experienced one of the most successful rebounds of its kind in North America, thanks to the revitalization efforts of Navajo parents, advocates and educators. With more than 169,000 speakers, it is the most commonly spoken indigenous language on the continent, the U.S. Census says.

Navajo is still at risk — as is every indigenous language in the world, according to the Endangered Languages Project. But some other languages are a few speakers away from extinction.

As soon as Tyler and Bryson arrive at school, their Diné day begins.

“Yá’át’ééh,” the principal greets each student.

One of the school’s goals is to help children become fluent enough to talk to their grandparents, hear the old stories and songs, and pass the knowledge to the next generation.

Amanda doesn’t want her children to be afraid of the outside world; the family takes trips to Disneyland and elsewhere. But she says the most important thing is that they feel a sense of identity in the traditional world.

“Otherwise, they don’t where they’re from,” she says. “They don’t know where they’re going. They don’t know who they are.”

Inside the family’s mobile home, where the foundation for that traditional world is being laid, Tyler is the gentle big brother, the one who doesn’t yell at his baby sister or get mad at his brothers for destroying his toys. He’s the one they climb on and call on for help.

“Once he was born, I always prayed,” Amanda says. “I prayed, ‘I want more of him.’” And my prayers were answered. With him, he was the mold. And how I’m close to him? That’s how I’m hoping it is with all my kids.”

Amy Linn has written about social justice issues for publications including the New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer and Salon. She can be reached by email through amylinn@searchlightnm.com.

In tiny Mosquero, ‘brilliant’ Kate is one of district’s 40 students

She lives in the least populated place in New Mexico — fewer than 700 people spread across 2,100 square miles in Harding County in the northeast quadrant of the state.

Her house — the same one where her mother grew up — is a block from her school, where she and 40 other children make up the entire student body from kindergarten through 12th grade.

She loves the Future Farmers of America and can talk at length about her passion for the organization. She hopes one day, when she’s older than 7, she can raise chickens.

For reasons only she knows — and she’s not telling — she likes to speak in a British accent. Last Halloween, she dressed as the queen of England.

Who is Kate Green?

If you ask her to describe herself in two words, those words will be “weird” and “weird.”

Weird is a popular concept with Kate, almost as dear to her as her Barbie dolls, her shelves of books and the time she spends working alongside her dad, Jake, in his woodworking shop in the family’s garage.

“Brilliant little kid,” says Tommy Turner, superintendent of the Mosquero Municipal School District, who pastures his horses on a plot of land that abuts Kate’s backyard and works with her mother, Margaret, the school secretary. “She’s so analytical. Those wheels are always turning.”

Kate’s is a middle-America life where mom, dad and daughter walk across the street to church every Sunday morning and gather each evening for dinner and talk.

And Kate can talk: “I help my dad work all the time. We work on the fence. He bosses me around. I work in Daddy’s workshop a lot. In the winter it’s always warm in there and I like the way it smells.”

Mosquero is perched all alone on the flat, grassy northeastern plains. Its population in the 2000 U.S. Census was 120. Ten years later, it dropped to 93. Children here are similarly spread out; Kate’s best friend lives a mile away down a dirt road.

Kate spends a lot of time with adults, and a lot of time in her room — reading, writing stories and playing with her toys. She’s content with her parents and grandparents, her vegetable garden, her bike and her replica John Deere tractor.

The best part about living in Mosquero?

“It’s a small town, “she says. “And I also like that bad guys rarely come here because there’s not like a jewelry story or a gold shop.”

Margaret, who grew up in Mosquero, and Jake, whose father is a cowboy on the nearby Bell Ranch, waited five years after marrying to have a child.

“Very planned,” Jake says. “I didn’t know what to expect, but I didn’t expect it to be this easy or this fun.”

When Kate was born, she almost immediately signaled she would be unique.

“She was very alert, very observant,” Margaret says.

When she started talking, her personality started to bubble out.

“I don’t think she has ever had a bad day,” says Marcie Pergeson, the teacher in the combined second- and third-grade classroom at Mosquero School. “She’s very blunt. She’s very opinionated. And, oh my goodness, she has the best sense of humor.”

Margaret, who went away to West Texas for college and loves books, started reading to Kate almost as soon as she was born. The first book she read aloud was “Pride and Prejudice,” begun when Kate was just 3 days old. Seven years later, Margaret has found an unexpected pleasure in motherhood.

“I love that I can carry on a conversation with my child,” she says. “Just talk with her. It’s fun.”

Leslie Linthicum has covered New Mexico as a reporter and columnist since 1982. She can be contacted at leslie@searchlightnm.com

In Chimayó, Heaven thrives amid lowriders

“I have two cars — one’s a VW Bug, one’s an Impala,” 7-year-old Heaven Chacon declares from the driver’s seat of a red 1961 Chevrolet Impala. And it’s true, her parents, Bobby Chacon and Pam Jaramillo, affirm: Heaven has chosen a Volkswagen and the Chevy as hers, while her sisters, Angel and Bobbie, have cherry-picked others from the dozens of 40 old vehicles (some restored, others waiting for renovation) that surround the family’s double-wide trailer in Chimayó.

These are no ordinary cars. Bobby, a co-founder of the Los Guys car club, is an aficionado of the custom car style known as the “lowrider.” Although Chimayó is more widely known for its ferociously flavorful chile peppers and for the Santuario, a 19th-century church that draws thousands of visitors to the Chimayó valley each year, lowriding is also a distinctive element of the cultural scene here.

Heaven has been “cruising El Norte” as a passenger since she was an infant. She looks forward to the day she’ll be able to drive the cars herself.

“My favorite things to do are to play outside with my friends, and go horseback riding and go fishing and go hunting,” she proclaims. “I like hunting because I get to shoot a .22, and I love to ride horses because the horses go fast and I don’t slip off — and I also like to go lowriding. It’s my most favorite thing because I get to ride in so many cars — and I don’t have to walk!”

Chimayó is home to some 3,000 people, most of them descendants from Spanish colonists who arrived in the early 1600s, though most families can also trace Native American ancestry. The traditional arts — weaving, wood carving, tin work and retablo-painting — are still practiced here. Many regard the art and craft of building lowriders, which are often decorated with murals derived from traditional imagery, as a natural extension of the people’s knack for self-expression through folk art.

Heaven’s family lives in one of the many mobile homes that now greatly outnumber the old adobe houses in Chimayó, in the middle of a patchwork of largely disused farm fields that spans the valley. Chimayó has never been clearly defined as a distinct town but rather comprises a loose collection of neighborhoods known historically as plazas or placitas.

Fifty years ago, Heaven would have said she was from the Plaza Abajo. It was only with the arrival of the U.S. Postal Service that the distinct barrios were grouped together under one moniker.

The spread-out nature of the community remains, as Chimayó is unincorporated and split between two counties, Rio Arriba and Santa Fe. The lack of public administration and authority leaves it in a kind of “in-between” place, which is both a blessing (taxes are low; rules and regulations are few) and a curse (public services are scarce).

Heaven revels in the rural life, though she acknowledges it has its rigors and challenges. Every year, she and her sisters pile in a big pickup with their father and uncle to drive for hours, buck up ponderosa pine logs and haul them back home to split into firewood. The work is but one of the many chores that Heaven helps with to keep the household going.

“I have to do everything,” she bemoans. “I have to get firewood, I have to get the trash, and I have to do the laundry, and I have to feed the cat … and sometimes my sisters help me, but sometimes they don’t!”

Even though the local grade school is only a mile away, her father takes her seven miles to James H. Rodriguez Elementary in Española. “We chose to start Heaven in kindergarten in Española because that’s where her older sister, Angel, and her tios went,” explains her mother, Pam. “And besides, it’s close to Bobby’s work.”

All schools in Rio Arriba County accommodate a large number of children facing learning difficulties, partly attributable to the tough socioeconomic conditions that are prevalent in the region.

In the state with the highest poverty rate in the nation (20.6 percent) Rio Arriba County sits about midway in the county ratings, with 22 percent of its residents living beneath the poverty line. Over 70 percent of K-12 public school students in Rio Arriba County participate in the National School Lunch Program. Circumstances such as these have been linked to low academic achievement and slow rates of academic progress.

Heaven, however, is doing well, earning As in all subjects.

“My favorite subject in school is PE, and math,” she says. “And my favorite thing to do in school is word searches.”

Heaven’s success is no doubt thanks, at least in part, to her stable and supportive family situation.

“I have a big family,” she says, “a lot of cousins and god-sisters and god-brothers and godfathers and a bunch of cousins and ninos and aunties. I like being the middle child, and what I like most about my family is that they help me, and they always take care of me, and they take me places.”

Heaven’s resilient, bright personality helps, too. When asked to pick a pair of descriptors, she doesn’t hesitate: “Two words that describe me are ‘strong,’ and ‘nice.’”

It’s hard to argue with that characterization when you see Heaven in her camo jacket behind the wheel of her Impala or slinging fire wood into the woodstove — always with a playful grin on her face.

Don J. Usner is a photographer for Searchlight New Mexico based in Las Cruces. He can be reached by email through searchlight@searchlightnm.com.

Boys learn the ropes on family ranch between 2-hour treks to and from school

The boys wake before dawn, eat sausage and biscuits in the cookhouse and saddle their horses at first light.

James Hurt is 12, a month away from becoming a teenager. His brother, David, is 11.

They wear Wrangler shirts, jeans and cowboy boots and move quietly in the dark corral, lit by a single bulb. It’s an autumn Sunday in 2017. Today they’ll help their Uncle Avery Hurt bring in from pasture a herd of hundreds of cattle.

It is a dangerous job, and they know it. They take ranch work seriously and see their future here.

James says he loves “the open land.”

“Like, in this part of New Mexico you can learn about it” — the land, he means. “You can learn from your family and learn about the place. You can travel across all this country.”

This “country” is the Alamo-Hueco ranch belonging to the boys’ father, William Hurt, a third-generation rancher in New Mexico’s Bootheel. The ranch — one of the state’s largest, a mix of private, federal and state land — stretches from the U.S.-Mexico border to the south and east, across hills of mesquite and creosote 35 miles north to Hachita.

It is a place of peace and beauty and significant risk: Drug smugglers have used the ranch roads to illegally move dope across the border. Last month, Border Patrol found 61 bundles of marijuana — weighing 1 ton, with a street value of $1.5 million — hidden near a dirt road.

Of living on the border, James says: “You have to be real cautious. You have to always look around you, especially in our southern pastures and also in our eastern pastures because there could be some illegal activity out there.”

Their mother, Lupe Hurt, is Mexican. She has always spoken to them in Spanish, so they know the language and use it to translate between the Mexican and Anglo cowhands who work the ranch.

On this Sunday, the sun climbs higher.

The Hurt boys help push the lowing herd into pens, then let the professional cowhands do the work of separating the bulls from the cows and the cows from the calves. The boys put their horses away and help by standing on a catwalk in the pens, whipping the animals as they push and shove their way into the corrals.

It’s weaning season.

Isolated from cell service and tasked with learning the family business, the Hurt boys have been riding horses, handling pocket knives, shooting guns and driving machinery for so long they can’t remember the first time they did any of those things. Their father is strict about safety.

“Being out here on the ranch out here is really fun,” James says. “It’s probably made my identity. It’s probably helped me become more influenced in this kind of work. It’s probably made me not as lazy as some other people I know.”

Hidalgo County is one of six “completely rural” counties in New Mexico, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The nearly 3,500-square-mile county averages just 1.4 people per square mile.

The boys have one of the longest bus commutes to school in the state, nearly two hours each way to and from Animas. The school runs a four-day week to make life a little easier for far-flung students.

James says they try to sleep after the bus picks them up at 6:10 a.m. On the way home, David says, he listens to country music.

“I think I learn more out here, because there is so much stuff I can grasp onto out here,” James says. “But I still need to go to school so I can know mathematics and English and language arts and science.”

James became class president in the fall at Animas High, an “A” school under the state’s grading system.

On the ranch, he says, “I can learn how to ride a horse, how to saddle my horse, how to work on stuff, how to run machinery, how to get a herd to do what you want — which is almost impossible sometimes.”

Lunch, homework — an exercise on pronouns for James, some book reading for David — then shooting practice in the afternoon.

They both want to go to college. James plans to study agriculture economics at New Mexico State University. Then they both want to return to the family ranch.

What is their favorite thing to do?

“Probably riding a horse,” James says.

David chimes in: “Riding a horse and processing calves and sorting and weaning and branding — and that’s about it.”

“You’re just naming it all, David,” James says, laughing.

“Yeah,” David says. “I like it.”

Lauren Villagran is a reporter for Searchlight New Mexico based in Las Cruces. She roams southern New Mexico and the borderlands she can be reached via Twitter @LaurenVillagran.

Editor’s note: This article was first published on Searchlight New Mexico and has been republished with their permission. Minor style changes were made with permission.