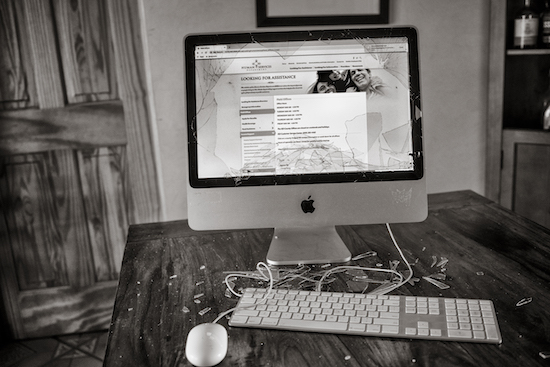

Nearly half of New Mexico’s population relies on a dysfunctional computer system for access to

government-funded health coverage, food assistance, heating and other benefits. That system

has repeatedly failed them, cutting off tens of thousands of children and families from their

financial lifeline.

Developed by the multinational corporate giant Deloitte at an initial cost of $115 million, the

Automated System Program and Eligibility Network — ASPEN for short — was intended to

streamline New Mexico’s processing of Medicaid and food stamps, as well as programs to help

the state’s poorest residents meet their most basic needs.

Child poverty in New Mexico is the highest in the nation. More than 820,000 residents rely on

Medicaid and other forms of public assistance, and Deloitte’s system serves as their

gatekeeper.

When ASPEN went live in 2013, a programming error summarily kicked tens of thousands of

children and families off of the benefits they relied on for food. Many were eventually able to get

their assistance back, but not before struggling to feed themselves for weeks or even months.

Some never regained their benefits.

In the following years, ASPEN routinely blocked eligible people from help. Parents in

Albuquerque were denied food stamps after they failed to show up to an appointment —

scheduled at an office more than 200 miles away. A single mother of four who earned $900 a

month submitted an application for food stamps, only to have the computer system swallow her

documentation and deny her case.

“I have had to turn to food pantries and other organizations for food donations to feed my

family,” Maria Ramirez of Anthony wrote in an affidavit for an ongoing lawsuit against the state’s public benefits system.

As complications overwhelmed unprepared human services employees, needy families were

lining up for hours outside their local offices in the early morning, waiting in sub-freezing

temperatures, hoping to see a caseworker.

The problems have continued right up to the present. For low-income residents and

caseworkers alike, ASPEN has turned what was supposed to be a simplified procedure into a

maze of glitches, incorrect calculations and vague or contradictory application instructions.

“The state bought a system that was a waste of money,” said Fred Garcia, union president of

AFSCME Local 3320 in Las Cruces. Garcia also works as an employee of the New Mexico

Human Services Department’s Income Support Division. “When they implemented the system, it didn’t work. It still doesn’t work — they’re still fixing it and fixing it and fixing it.”

Employees in local public benefits offices have reported system malfunctions and other

problems more than 37,000 times since January 2017 — an average of 80 times per business

day, according to records obtained by Searchlight New Mexico. Some of those errors deny

benefits to eligible people. Others dole out excessive benefits or award assistance to people

who should not qualify.

Deloitte, which last year boasted a record $43.2 billion in revenue, is paid to fix the system’s

ongoing malfunctions on the taxpayer’s dime.

This fiscal year alone, New Mexico taxpayers will hand Deloitte up to $773,361 per month for

handling help-desk tickets and maintaining the software.

“It’s been a double drain on the people of New Mexico, who aren’t getting the food and medical

care that they need and instead are paying for [Deloitte’s] mistakes,” said Sovereign Hager, an

attorney with the New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty, which monitors ASPEN as part of a

court-ordered agreement.

New Mexico isn’t the first state to have its Deloitte-designed eligibility software implode. From

Oregon to Rhode Island, state governments have shelled out billions of dollars to Deloitte for

these so-called integrated eligibility systems, only to see those systems melt down, leaving poor

families without a safety net.

In Rhode Island, the Deloitte-designed system malfunctioned so spectacularly in 2016 that the

American Civil Liberties Union and others filed a class action lawsuit, resulting in the

appointment of a special master to force the state into compliance with federal law. Two of that

state’s top human services officials resigned, and Deloitte issued a public apology.

Over the past two years, Rhode Island has withheld payment to Deloitte because of the

malfunctioning software.

Widespread problems with Deloitte eligibility systems have similarly been reported in Illinois,

Kentucky, Georgia, Texas, Michigan and elsewhere.

Deloitte declined to comment for this story.

“We tend to see cascading series of things that go horribly wrong” when states roll out Deloitte-

designed systems, said Marc Cohan, executive director of the National Center on Law and

Economic Justice, a national nonprofit based in New York that joined in the class action suit in

Rhode Island.

Often states have rushed to implement the software before it’s ready — sometimes under

pressure from Deloitte, according to workers in several state governments. Wooed by promises

of an ultra-efficient state-of-the-art system, many states have slashed staffing levels in human

services offices, only to be caught flat-footed when problems become apparent.

“It’s a rare state that takes the time to do it slowly, carefully, and not use it as an invitation to

reduce staff,” Cohan said.

Mess with Texas

Established in nineteenth-century London, Deloitte has grown to become the one of the largest

multinational companies in the world and the fourth largest private company in America, with

operations running the gamut from accounting services to risk management and auditing

programs for Morgan Stanley, Boeing and other Fortune 500 companies.

In the past several decades, the company has found a new money maker in computer systems

for managing Medicaid and other public assistance programs.

Deloitte found its first customer in Texas in the early 2000s. Looking to the private sector in an

effort to cut costs, the Texas Health and Human Services Department signed a contract with

Deloitte to design a software program that would streamline the processing of $18.2 billion in

benefits for the four million Texans who relied on Medicaid, the state Children’s Health

Insurance Program, food stamps and TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families).

But when the state rolled out its program, the system ground to a near halt, and backlogs

snowballed. The software was calculating eligibility incorrectly, stacking up errors and dropping

eligible people from coverage, according to several attorneys and human services officials.

Anne Dunkelberg, Associate Director of the Austin-based Center for Public Policy Priorities,

described Deloitte’s software as contributing to “what was essentially the meltdown of our

eligibility system for a number of years.”

Just four months after rolling out the pilot system in Texas, the state government had to halt the

program until Deloitte could get it to function properly — a process that would take eight

painstaking years.

At the same time, Deloitte was already marketing its software elsewhere. In 2004 the company

began work on an integrated eligibility program in Michigan, at an initial cost of $207 million,

using the same coding that was causing havoc in Texas.

“It was just filled with glitches,” said Jackie Doig, a former attorney with the Center for Civil

Justice, a Michigan-based poverty law group. Doig described an unraveling of the state’s

Medicaid and public benefits system that mirrored Texas’ experience just a few years earlier,

with the Deloitte software issuing incorrect calculations and dropping people from coverage as

system malfunctions overwhelmed IT support staff.

The same scene played out in Illinois, Kentucky, Rhode Island, Georgia, Oregon and almost

every other state that bought into Deloitte’s software. New Mexico entered the field in 2011,

when it invested $115 million in a project to upgrade its eligibility program.

Some states have been able to turn their troubled Deloitte systems around. Texas, most

notably, undertook an exhaustive effort to iron out the glitches with the help of outside experts.

“Eventually a lot of these things get worked out. But in the meantime, a lot of people get hurt,”

said Stanley Stewart, a former consultant hired to fix that state’s program.

Other states, meanwhile, continue to struggle. In New Mexico, human services officials deny

that the software is problematic at all — even as eligible residents are unable to access benefits

because of ongoing programming errors.

Impromptu patches multiply troubles

For the one in five New Mexicans living below the poverty line, even minor disruptions can send

families careening towards hunger or homelessness. Many of these families rely on a program

known as expedited SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) — an emergency food

assistance program meant to provide immediate help to individuals and families at risk of going

hungry.

With Deloitte’s computer errors jamming the gears of the expedited SNAP program, the state’s

most vulnerable residents are regularly denied emergency food assistance.

In one example uncovered by Searchlight, an ongoing programming error in ASPEN fails to

deduct utility expenses, as required by law when calculating benefits, from very low-income

residents applying for expedited SNAP. As a result, an applicant’s income is artificially inflated

— in many cases incorrectly disqualifying people from the program.

Some offices of the Human Services Department instruct employees to manually fix that

particular error in applicants’ eligibility calculations. In other offices, management doesn’t inform workers of the error at all, according to interviews with HSD employees in four counties.

Employees in at least one office report being instructed not to change ASPEN’s erroneous

calculation for expedited SNAP.

“You just sit and watch the system denying people that should be eligible,” said Fred Garcia, the

union president and HSD employee from Las Cruces.

Similar glitches have kicked foster children off of Medicaid and incorrectly denied health

coverage to lawfully residing immigrants who are pregnant.

Deloitte has not adjusted its system to each state’s specific standards. Remnants of state-

specific policies from Michigan and Texas remain imprinted in New Mexico’s programming,

knocking calculations out of whack with state rules, according to employees and attorneys

familiar with the system.

Nearly 2,000 state employees use the ASPEN system, many of them manually tweaking the

computer’s calculations to account for the widespread glitches. With computer errors occurring

in nearly every application for public benefits, employees have to invent their own fixes by

manipulating the information on the screen in order for the result to be correct — pushing the

entire system further out of balance.

“We never received any real training when ASPEN went live, and we still haven’t gotten any

training,” said an exasperated caseworker who, not authorized to speak with the media and

fearing retaliation, spoke on the condition of anonymity. This employee and multiple others

described a work environment marked by high vacancy rates and a relentless push by

management to meet quotas for processing applications for assistance — frequently being

assigned dozens of cases daily, each with a strict time limit of 15 or 30 minutes, depending on

the type of case.

As employees continuously scramble to meet quotas using a dysfunctional computer system,

many quit their jobs — sometimes walking away from good salaries and retirement plans —

leaving their coworkers with even higher workloads.

The problem has drawn criticism from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services,

which in 2017 issued a reprimand over New Mexico’s ASPEN system and demanded a

corrective action plan to stop the extensive use of workarounds.

“I am at my wit’s end,” said the employee.