By Ted Alcorn/ New Mexico In Depth

Alcohol is killing New Mexicans at a higher rate than anywhere else in the country — yet the state has largely neglected the growing crisis. In this seven-part series from News Port partner New Mexico In Depth, journalist Ted Alcorn investigates the state’s blind spots and shines a light on solutions.

In New Mexico’s war on DWI, the relentless focus on drunk drivers misses the bigger problem of addiction.

“I want to see bad driving.”

New Mexico State Police Lieutenant Kurtis Ward scanned traffic, weaving his Ford Expedition through northbound traffic on Interstate 25. It was 8:37pm on a wintry Friday night. A full moon was cresting the Sandias.

The workday of the DWI Unit had just begun.

“I watch for that car that’s doing something that’s different,” he said. “The one that stands out: I want to watch that car.”

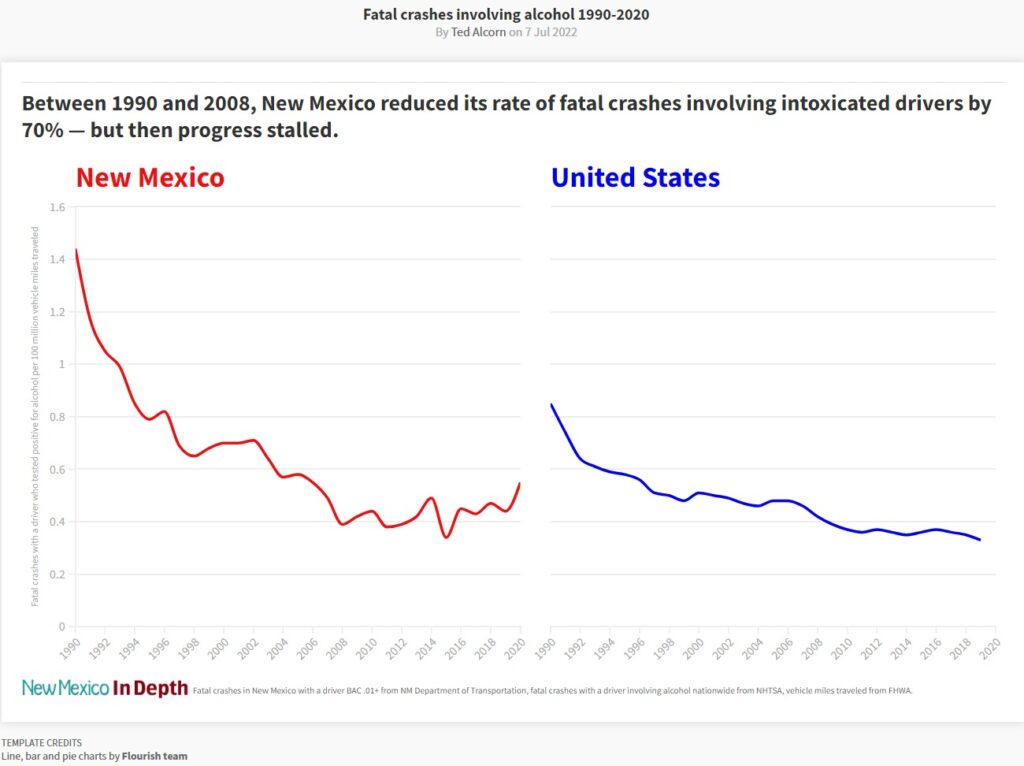

For a generation, the state has spent tens of millions of dollars a year to curb intoxicated driving and its toll on New Mexicans. In-school programs and public information campaigns advertise the legal and physical consequences intoxicated drivers risk. Ward passes a billboard of the Department of Transportation’s END/DWI campaign adorned with one such message. “Be Safe, Not Sorry,” it cautions. But his eyes and presence on the road are at the heart of New Mexico’s strategy: identifying and removing intoxicated drivers, and alerting other motorists that the state is watching. The efforts have saved hundred of lives and, for a time, made New Mexico’s roads safer. But a New Mexico In Depth analysis of traffic fatality data shows in the last 15 years, progress has stalled. New Mexico’s rate of fatal intoxicated driving crashes has even begun to creep upward, compared to national rates. This raises an uncomfortable question: Will continuing to focus on drivers and roadways further reduce crashes and deaths?

While the state’s campaign against DWI shows it can tackle deeply ingrained behaviors involving alcohol, it might be too narrowly focused. Of alcohol-attributable deaths in New Mexico today, 10% are traffic fatalities; the other 90% have nothing to do with the road.

Michael Landen, who was the state epidemiologist until 2020, puts the state’s approach into perspective.

“DWI is one piece of a much bigger problem.”

The turnaround

In the early 1990s, intoxicated driving was an enormous, neglected hazard that many New Mexicans believed was beyond the reach of public policy. Fatal crashes involving alcohol were 70% more frequent on the state’s roadways than the country’s as a whole, controlling for miles traveled. There were 232 in New Mexico in 1990, outnumbering fatal crashes in which drivers were sober.

A report prepared by then-Attorney General Tom Udall diagnosed the state’s problems: widespread ignorance of the risks, little outrage about intoxicated drivers, lax practices by bartenders and liquor store staff, inattentive law enforcement, and inconsistent sanctions in the courts.

But overwhelming tragedy can prick the public’s conscience. On Christmas Eve of 1992, an intoxicated man drove 12 miles the wrong way against highway traffic before striking head-on a family out caroling, killing Melanie Cravens and her three young daughters. The crash and trial made national news and converted the family’s matriarch, Nadine Milford, into one of the state’s most powerful advocates for traffic safety. It also forced the governor and Legislature into action.

And the state responded in sustained and systematic fashion. It lowered the legal blood alcohol limit from .10 to .08 and required driver’s safety education and alcohol server training. People with repeat DWI convictions would serve mandatory jail time, increasing with each offense from days to weeks to months and finally by the fifth conviction to a year or more. The Legislature raised the state liquor excise tax and used the revenues to fund new county-run anti-DWI programs.

Later, the state would close drive-up windows at liquor stores and pass a first-in-the-nation law that required people convicted of a DWI to equip their car with an ignition interlock, a breathalyzer they must submit to before starting the car. To this day, the program earns Mothers Against Drunk Driving’s highest rating.

Lindsey Valdez, who runs the state’s chapter of MADD, said the whole of these changes was greater than the sum of the parts, and produced “an overall cultural change,” both in the citizenry and in government.

Rachel O’Connor, who Gov. Bill Richardson appointed to his cabinet in 2004 as the state’s first DWI Czar, said she was well-funded, had buy-in from nearly every state agency, and robust data “so you could look clearly at and be strategic about where the fatalities and injuries were occurring.”

And there were irrefutable changes in outcomes. Between 1990 and 2008, fatal alcohol-involved crashes in New Mexico dropped 56% even as motorists drove far more, and the state’s rate of fatal alcohol-involved crashes fell in line with the national average.

The stall

Ward was a part of this cultural change. As a teenager, he himself was almost killed when an intoxicated driver t-boned his car at an intersection in southeast Albuquerque. He followed an uncle into the state police in 2001 and started its DWI unit. In the years since he has racked up more than 2,000 DWI arrests.

But it came at a price. Over the years, Ward and his fellow officers worked countless grueling nighttime shifts, leaving a few hours for sleep before reporting to court in the morning to testify about prior arrests, then heading back to the streets. “If you have a family and you just want to be a normal person, it’s very hard to make those two worlds mesh,” he said. He missed his son’s school events and birthday parties. His marriage fell apart. “I was killing myself to try to save other people from getting killed.”

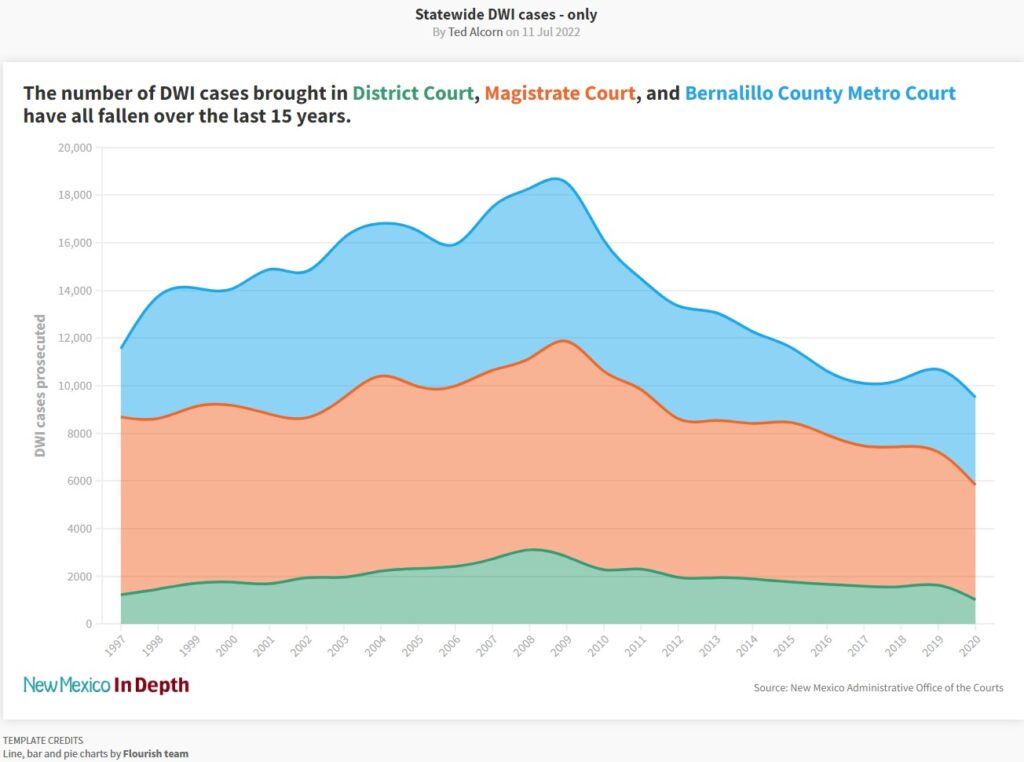

Gradually — nearly imperceptibly — DWI arrests have become more rare. Statewide, cases prosecuted fell from 20,000 to 10,000 annually, according to data from the Administrative Office of the Courts. Ward’s specialized unit hasn’t shed officers or changed practices, he said, and his personal passion for the work hasn’t wavered, either, but he’s noticed the change. “It’s harder for me now to find a drunk driver than it was 10 years ago.”

This trend would be favorable if it meant fewer people were driving drunk, but the decline in DWI arrests does not seem to indicate that fewer drivers are impaired or the roads are safer

For the last 15 years, the state’s rate of fatal alcohol-involved crashes has been flat and recently began to tick upward: there were more fatal alcohol-involved crashes in 2020 than in any year since 2007.

The strategy has been worthwhile and should continue, said state Traffic Safety Director Jeff Barela, but it’s not enough. “We’re still doing the enforcement, we’re still developing the campaigns and putting the awareness out there,” he said. But “it’s just kind of stagnated.”

Shifting focus from driving to drinking

When state police set DWI checkpoints in heavily trafficked areas, it’s partly a performance meant to deter drivers from even considering getting behind the wheel when they are intoxicated. But Ward and the larger criminal justice system arguably have greatest influence over intoxicated drivers they catch and convict — and as a share of the total, that group is shrinking.

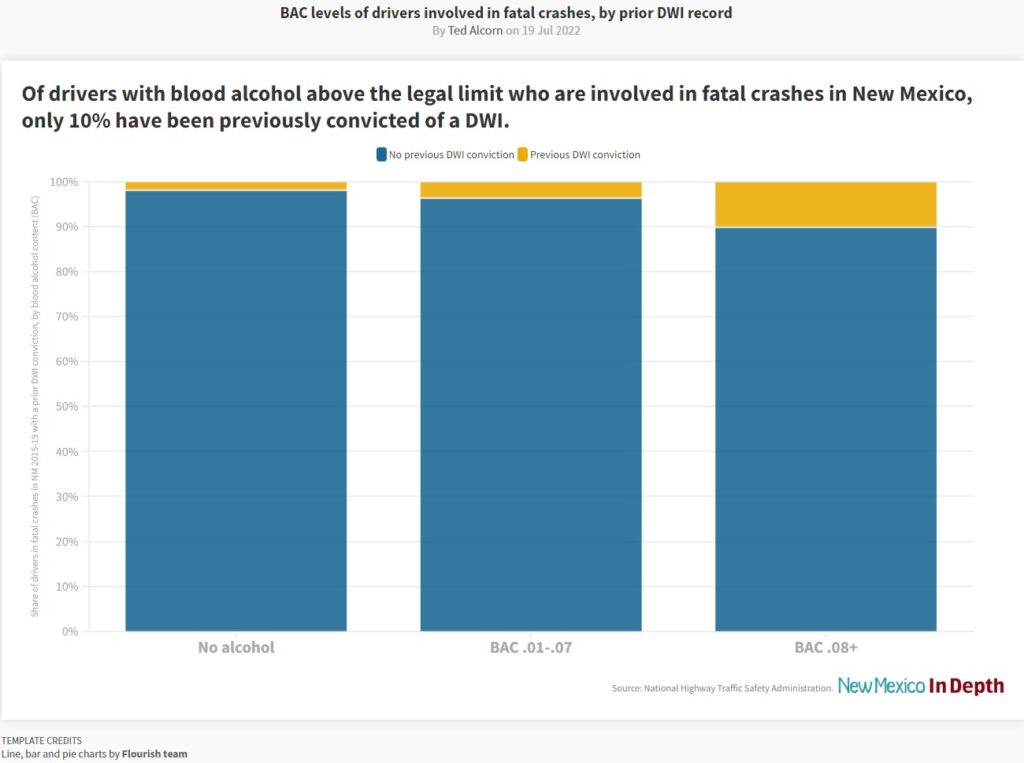

In 2019 only one in three people convicted of DWI in New Mexico had a prior conviction, down from 42% in 2009, according to a New Mexico In Depth analysis of transportation department data. And when alcohol mattered most — fatal crashes in which at least one driver had a blood alcohol level above the legal limit — fewer than one in 10 involved someone previously convicted of a DWI, according to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data.

That means in the vast majority of such crashes, the intoxicated driver never passed through the systems of enforcement and education that are the core of the state’s anti-DWI strategy.

Even when enforcement was at its peak, police never swept up more than a fraction of intoxicated drivers.

That’s plain from comparing the rate at which people report drunk driving to the number caught doing it: based on national surveys showing 1% to 2% of people drove impaired in the last month, researchers conservatively estimate there are well over 100 million incidents of intoxicated driving each year — compared to about a million DWI arrests.

Advocates often say the average person who drives intoxicated may do so a hundred times before being caught. Put another way, for every person who is arrested, there are 99 drunk drivers on the road who aren’t.

That’s why focusing on what happens after arrest has a limited effect compared to the conditions that enable intoxicated driving, said Bennett Baur, the state’s Chief Public Defender. “Using the mechanisms of the criminal system to try to solve a problem will always be very incomplete,” he said.

To get a broader view of intoxicated driving in New Mexico, the optimum vantage point may not be from behind the wheel of a police cruiser but in the Metropolitan Court’s DWI First Offender Program, where most people convicted of their first DWI in Bernalillo County serve their sentence.

Chief Probation Officer Andres Garcia said it is by far the largest program he oversees, with nearly 1,000 participants at any given time. “We have doctors, attorneys, we have lifelong convicted felons, we have regular Joe and housewives.”

Participants must pay to have an interlock installed in their vehicle and attend a victim impact panel where they hear about the consequences of drunk driving from people harmed by it. Twelve hours of “DWI School” is mandatory, too

Tomás Butchart, a retired elementary school instructor and administrator, began teaching the course about 10 years ago. The stream of pupils is constant: at any given time, two groups of about 20 students each, and the courses run 50 weeks a year, with separate instructors handling other sections.

On a Tuesday in March, he welcomed a new group via videoconference. For a few hours that evening and in the weeks that followed, he guided them as they reflected on the circumstances of their offense, their drinking habits, and their plans to change.

Their arrests ran the gamut of New Mexicans’ risky alcohol-related behaviors. “I tried to get an Uber but it was in the middle of the pandemic and it was pretty impossible that night, so I made the poor choice to get in my car and try to go home,” said one.

“I drank 10 or 15 miniatures of 99 Apples and then me and my girlfriend started to argue, so I just took off to go to my mom’s house and I rolled my car,” said another.

“One of my buddies got back from a deployment and I graduated from nursing school.”

“I was having a real hard time.”

“I was coming back from a funeral.”

In the environment and society they described, alcohol was a near constant presence — which suggests that preventing future crashes could require broadening the state’s long-standing focus from drivers to drinking itself.

O’Connor, now the director of Santa Fe County’s Community Services Department, can see the limits of the approach they took in the early 2000s. “I think we did a really good job of reducing impaired driving in New Mexico, but the issue of addiction is alive and well.”

Today’s lawmakers have shown little appetite for addressing the state’s broader culture of alcohol consumption. The omnibus package of legislation passed to address DWI in 1992 was the last time New Mexico raised alcohol taxes, despite studies showing it reduced intoxicated driving fatalities and other alcohol-related harms in states that did so.

And in 2021, state Rep. Antonio “Moe” Maestas, D-Albuquerque, led successful efforts to allow home delivery of alcohol, among other reforms, which he argued would reduce DWI rates by eliminating the need for inebriated drivers to leave home to buy more alcohol. “Delivery is going to save lives,” he said in an interview.

Public health experts strongly disagree. “If there were a shred of science to support his assertion, I would be all for it,” David Jernigan, a professor at Boston University School of Public Health, said by email. Easing access to alcohol is the opposite of what the state needs to reduce its consequent harms, he continued. “The very notion of drunk people sitting at home and needing more booze ignores the myriad complications of heavy drinking that have nothing to do with drunk driving.”

Butchart imagined a world that acted before people drove intoxicated, rather than after the fact. “Instead of those officers being out there waiting near a bar for people to get into their cars, they should be at the exit themselves saying, ‘If you’ve been drinking, you better not get into a car.’”

“I wish it was different,” he added, “but my phone is not ringing off the hook with calls from the chief of police asking me what should be done.”

Ted Alcorn is a writer raised in New Mexico whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The Washington Post Magazine, among other publications. For New Mexico In Depth he’s investigated how the state’s prisons have ignored an epidemic of hepatitis C, how Albuquerque stood up its branch of non-police emergency response, and how non-profit hospitals shortchange community health. Follow him at @tedalcorn

This story was originally published by New Mexico In Depth