By Alicia Inez Guzmán/ Searchlight New Mexico

TIERRA MONTE — Ever since the start of the monsoon season, a torrent of boulders and debris has tumbled down the mountainside toward the Encinias family home, only months after the land was laid bare by fire. On April 22, the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon blaze consumed almost everything around them, including their five-bedroom house, private well and most all worldly possessions. Since then, the family of five, their four dogs and eight cats have lived in a 38-foot RV.

The summer has been unspeakable for Daniel and Lori Ann Encinias’ three youngest daughters, who, in the coming days, are slated to return to school: Amanda, 18, at Luna Community College, and Justina, 16, and Jaylene, 15, at Robertson High School. For them and countless others, catastrophe overshadows their return to learning.

“The only thing we want is to be able to get a house,” says Justina, known to her sisters as Jayjay. Classes, school supplies, band — the sisters’ favorite — all seem insignificant now, as they gather on the front steps of the RV. The rubble around them is a constant reminder of their loss.

Their new reality is defined by cramped bunks and hauling water from a relative’s house to replenish the RV’s single shower. Getting ready for school every morning on the limited tank will be “the hardest thing,” Justina predicted, looking to Amanda and Jaylene for confirmation.

Besides the clothes she wore, Justina saved Ruby, her childhood stuffed rabbit, and a camera her parents bought her for Christmas. Beyond that, the Enciniases walked away with a handful of framed family photos, their pets and each other.

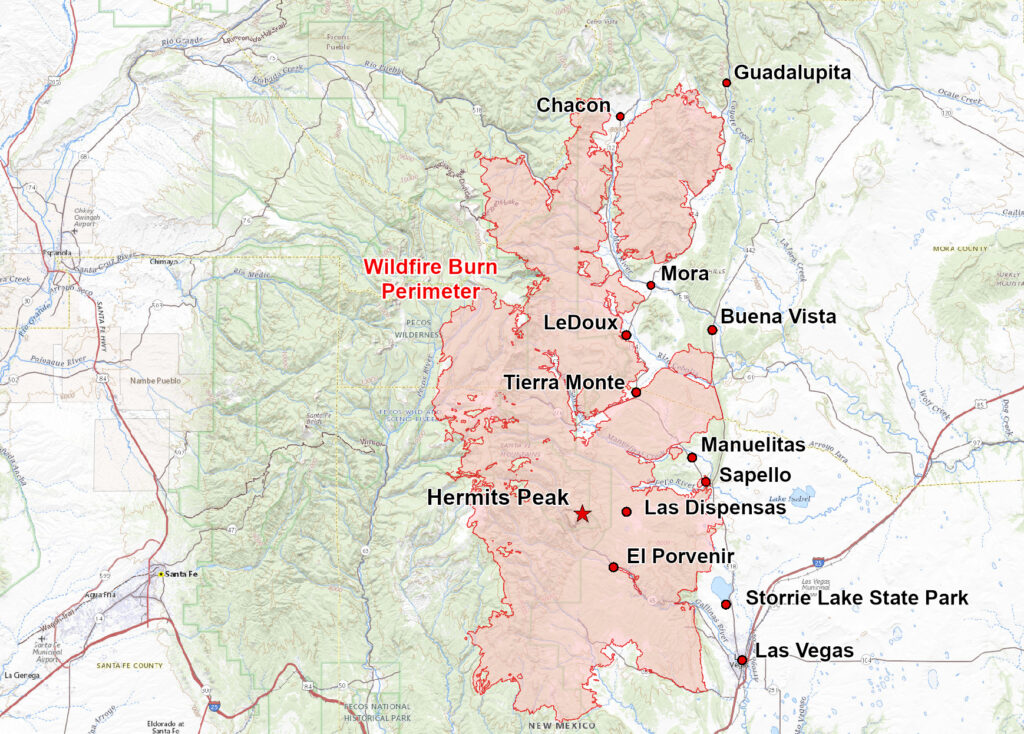

The family’s land sits near the beginning of the wildfire zone, a roughly 50-mile expanse of rural area served by three public school districts: Las Vegas City Public Schools, West Las Vegas and Mora Independent Schools, with an estimated 3,200 students between them. First, the blaze ravaged several small villages south and east of Hermits Peak, including El Porvenir, Las Dispensas, Sapello and Manuelitas. Then it tore north toward Pendaries, Rociada and Tierra Monte, finally sweeping much of the Mora Valley — home to more than 1,500 people.

When asked how many Mora families with school-age children were affected, the director of the Mora Head Start program answered: “all of them.” The damage, in Joseph Griego’s estimation, was so comprehensive that every person in the Mora Valley is suffering the consequences.

Perhaps the most urgent problem, Griego says, is the lack of drinking water. Between the blaze and the floods that followed, local wells and watersheds were wholly destroyed or gravely jeopardized, leaving the school district, county officials and water authorities scrambling for a solution.

All of that, Griego reckons, is just a “multiplier on the impact that the fire had.”

In the aftermath, Marvin MacAuley, Mora’s school superintendent, sees the district’s mandate anew: to help the entire community face some of its most pressing challenges. He’s a firm believer in psychologist Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs,” a theory that people must get essentials like food, shelter and safety before they can pursue inner potential.

“We have to meet our families’ basic needs to get the students prepared to learn,” he says. “Because if their basic needs aren’t met, we’re not gonna get much learning done.”

Trauma upon trauma

A catastrophe often comes in waves. The first in the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon fire took place in April, while school was still in session. Flames chased families from their homes and scattered them for months at evacuation shelters, relatives’ houses, hotels and campgrounds. Students, who stayed up all night working with their families to evacuate livestock, came to class exhausted.

Schools went remote for a time, but that triggered other problems: Nearly everyone felt like it “brought up past trauma” from the days of the pandemic, said McKaila Weldon, an art teacher at West Las Vegas High School. “I don’t want to do it,” some told her.

With each new phase of the fire came a new evacuation. In April, the entire student body of Mike Mateo Sena Elementary school was relocated from the village of Sapello, near Hermits Peak, to Sierra Vista Elementary, in Las Vegas.

Monica Martinez said the evacuation was traumatic for her youngest daughter, 10-year-old Kateri, as well as for other children. When Martinez, who lives in Las Dispensas, arrived to pick up Kateri on evacuation day, police had commandeered the building, shuffling children out of classrooms. The blaze was still miles away, but smoke billowed from behind the hills.

“Kids were wondering why cops were in the hallways,” Martinez recalled. “They didn’t know what was going on.” The blaring police lights, the sense of disarray — all of it brought to mind school shootings, she said.

‘We’re not canceling’

After the blaze took everything, the Encinias family faced additional chaos: Their RV wasn’t big enough to hold the three younger children plus their oldest daughter, her boyfriend and their three children, who had previously lived in the Encinias’ large home. They had little choice but to move out. The rest of the family spent the last month of school living in the RV at the campground at Storrie Lake State Park.

Some days, Lori Ann took the girls to school; other days, Robertson High School’s bus picked them up and dropped them off at the campground. When Amanda graduated, Daniel and Lori Ann still managed to host a graduation party — not at their home, as planned, but at the Elks Lodge in Las Vegas, some 20 miles south.

“We may have lost everything,” Daniel told his wife, determined to keep some semblance of normalcy, “but we’re not canceling nothing.”

As evacuation zones reopened, he and other locals returned to the desolation of their property, where acres and acres of land had been devastated, cattle lacked feed and the little timber left wouldn’t be enough to sell or use for warmth in winter.

Power lines that were cut off or burned in the fire wreaked another kind of havoc: Without electricity, freezers and refrigerators full of food spoiled, costing residents hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to replace. With power lines down for most of the summer, Daniel, a retired electrician, relied on two generators for the family’s RV. They cost an astonishing $3,600 over a two-month period.

Small mercies, large losses

Monica Martinez and her family finally returned home from the Glorieta evacuation center at the end of May, after stints of staying in hotels and with her in-laws. Her house still stood, which she attributes to her husband, who stayed behind to protect it in the early days of the wildfire. But no one could prevent the flames from zigzagging across their land, scorching some of it beyond recognition.

Among the greatest casualties was the Martinez’s private well. With no running water, Monica took the children to the campground showers at Storrie Lake, until the city of Las Vegas shut them down as a conservation measure. The family now showers at a local Love’s Travel Stop, which charges $15 for 30 minutes, she said. Every week, she pays $80 to do laundry at a laundromat.

Other costs have also added up — gas for all the travel into town and paper plates and plasticware for all the dishes she cannot wash. For drinking water, she and her husband used to haul 5-gallon tanks from the local fire station and campground for free, but with Las Vegas’s emergency water shortage, they have recently begun buying it at a store. Water to flush their toilets and wash their hands comes from a nearby windmill that managed to escape damage.

The family received $500 from FEMA for evacuation costs, Monica said, but the money hardly compares to all they’ve been forced to spend since their return home. It’s not lost on them that the U.S. Forest Service is to blame for the fire and for their struggles. “We’re dealing with stuff we didn’t need to go through,” she says, the frustration palpable. “That we didn’t choose to go through.”

From fire to flood

In the Mora Valley, the wildfire’s burn scar stretches across a constellation of canyons and tiny unincorporated villages — from Chacon, Guadalupita, Holman and Cleveland to Buena Vista and LeDoux. Local roads, each a connective artery, have turned into rivers in recent weeks under the battering of relentless rains. In August, flash floods in the burn zone killed one man who was driving in the Mora area; two women and a man perished when their car was swept away near Tecolote Creek, northwest of Las Vegas.

The fire charred thousands of acres in the Gallinas River watershed, which provides water to Las Vegas. In the Mora Valley, the blaze burned so hot it cracked the rock beneath a spring that channels water into Chacon, impeding its flow almost completely. Culverts have been crushed by boulders and mud in the floods and tarry sludge trickles down the path of age-old acequias.

“We haven’t had rain for so many years, and now we’re getting the rain — and we want it,” said Joseph Griego, the Head Start director. “But there’s nothing to hold it back. There’s nothing to keep it from washing all the debris into the roadways, into the rivers and now into the water sources.”

The resulting floods have unleashed new rounds of evacuations and inflicted even greater damage to water systems, homes, buildings and infrastructure.

In Chacon, a village of 370, locals must first repair a washed-out road before 2,000 feet of incinerated pipeline can be replaced. In Buena Vista, some locals reportedly resorted to filling buckets of water from acequias just to flush toilets because their well water was depleted by firefighters. As a temporary stopgap, tankers of water — pulled from the Mora Independent School’s wells — are delivered to Chacon and Buena Vista multiple times a day.

The storms struck with such force and regularity that the National Weather Service in Albuquerque has issued a flash flood watch in the burn scar nearly every day since the beginning of July. The rains threaten to make bus routes impassable when school starts.

Mora Independent Schools, in response, is beginning classes one week later than planned, hoping for drier weather by the time children and parents have to get on the roads. In the event that the monsoons do lead to closures, school officials have finalized a flood evacuation plan that includes provisions for ending school early or sheltering in place. Mora County has also allotted special weather radios to residents as part of an early warning system.

Learning will only be possible if the district “supports our families and gets them on their feet,” Superintendent MacAuley says.

Food, hay and supplies needed

The challenges are profound. Food insecurity, a long-running problem for low-income families in rural New Mexico, peaked during and after the fires, said Jill Dixon, deputy director of the Food Depot in Santa Fe. In May, the nonprofit’s distributions at the Mora Head Start building — a centerpiece of relief efforts — totaled 119,000 pounds of food. In the months since, approximately 920 people have consistently received food in the Mora area, a number that has not dropped, Dixon said.

The Mora Head Start building, a clearinghouse for fire updates and community forums, also became a distribution spot for donated firewood and five semi-loads of hay.

Most farmers and ranchers aren’t running booming businesses: They depend on small herds for their livelihoods, Griego said. The largest, he noted, is 57 head, the smallest two. Almost all were able to get feed from those semi-loads, thanks to a collaborative effort by multiple entities.

“The community and kids have been hit with everything possible over the past three years” — the pandemic, the fire and the floods, Griego said. “It’s not a good environment, but the district has been trying to do as much as it can to provide for the community.”

‘Expeditionary learning

The number of children affected will likely grow so long as the waves of complications continue. To meet the needs, Mora Independent Schools hired a second social worker, available for a new hands-on curriculum called “expeditionary learning.” The goal, said Tracy Alcon, principal of Holman Elementary school, is to get kids outside and thinking: “How does the world heal from something like this?” When they do, she went on, “they might walk away with a bigger view than oneself.”

It might be hard, in the present moment, to imagine that bigger view — to imagine a future that isn’t wholly defined by the historic wildfire. Simply getting through one day in a landscape so radically altered takes up enough energy.

Daniel Encinias, for his part, is preoccupied with clearing away debris from the family property, creating diversion channels and moving the giant boulders that spilled off the mountaintop into the gaping potholes the floods cut in his driveway. He plans to put down a doublewide on the original house foundation by winter. It’s not the same as the home he spent years building, but it’ll do for now.

“Home is where we are,” he reminds his family, daily.

He has little faith that the forest will recover in his lifetime. “They’ll see it come back,” he says hopefully, gesturing toward Justina and Jaylene.

Jaylene, who once had a view of the vast expanse of Peñasco Blanco from her bedroom window, worries it won’t be “the same way we saw it.”

Justina is more optimistic. “It will be better. Stronger,” she says.

Searchlight New Mexico is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.