By Gwyneth Doland/ New Mexico In Depth

New Mexico lawmakers protected themselves and their colleagues when they redrew political district maps crafted by a 2021 nonpartisan advisory commission, shielding incumbents of both parties from competition and making legislative elections less competitive, according to a new 59-page report co-authored by University of New Mexico political science professor Gabriel Sanchez.

The study, released Sept. 28, found no evidence that New Mexico Democrats, who have strong majorities in the House and Senate, politically gerrymandered their districts, a conclusion based on statistical analysis conducted by Sanchez’s co-author and University of Georgia professor David Cottrell.

“The protection of incumbents was the greatest source of gerrymandering this session,” the authors concluded, based on the analysis and interviews with experts.

That outcome resulted from inherent weaknesses in how lawmakers set up the state’s new Citizens Redistricting Committee – the committee doesn’t have final say on what redistricting maps are adopted, the report found.

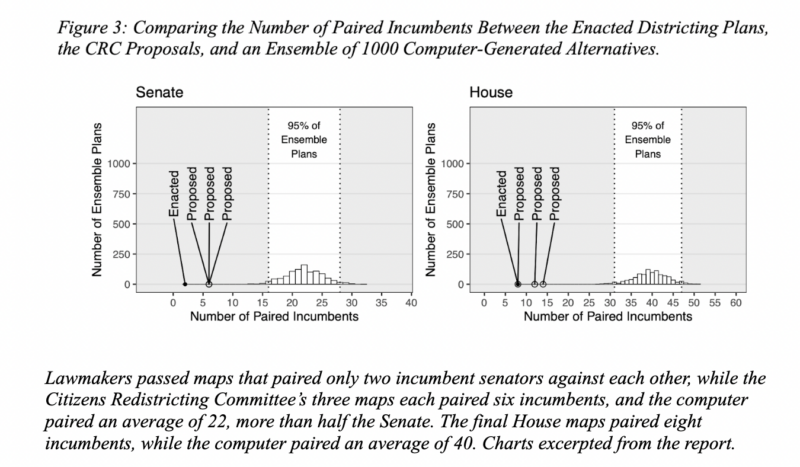

State lawmakers crafted districts in which far fewer sitting legislators would have to run against each other, compared to districts created by a computer program used in the study that did not take into account where incumbents live. In fact, 95% of more than 1,000 computer generated maps paired far more incumbents than the state’s new advisory Citizens Redistricting Committee or the state Legislature.

Critics call protecting incumbents “buddymandering” and argue that it distorts the democratic process in favor of politicians instead of the public.

Dick Mason of the New Mexico League of Women Voters, and a member of the New Mexico Redistricting Task Force, said he’s glad the report emphasized this lesser-known form of gerrymandering.

“Incumbency protection is a basic violation of one-person-one-vote,” Mason said. Moving voters into districts that limit competition means an individual’s vote there matters less than it otherwise would.

For years state legislators across the country have avoided pairing incumbents when redrawing political maps and the practice is allowed in more than 30 states. But as more states move toward reform, it has started to fall out of favor.

A 2019 analysis of redistricting in seven western states found New Mexico was the only one that specifically listed “avoid pairing incumbents” as a guideline.

The new study echoes New Mexico in Depth’s 2019 report on redistricting, in which multiple sources, including sitting lawmakers of both parties, openly described the state’s redistricting process as an “incumbent protection plan.”

Still, the concept isn’t particularly unpopular with the public. A poll of 500 “highly likely voters” conducted for the report shows that 40% of New Mexicans think it’s OK to consider incumbents’ addresses in the process, while only slightly more, 43% don’t want the information used.

In one way, the critics are winning; New Mexico’s new Citizen Redistricting Committee can’t consider where current elected officials live. But the Legislature, which can overrule the Committee’s maps, has long said that state lawmakers can—and should—avoid pairing incumbents.

Independent redistricting committee has “important weaknesses”

In 2021, the state Legislature bowed to more than a decade of pressure and agreed to create an independent Citizens Redistricting Committee. But the committee fell short of what advocates had lobbied for: a truly independent commission whose decisions were final and not advisory. Instead, state lawmakers have the authority to adopt, adjust or ignore the committee’s work.

Sanchez and his co-authors wanted to look at whether the new committee improved on what many have described as a flawed system. They examined the results of the state’s most recent redistricting through map analysis, a statewide online survey, and interviews and focus groups.

Their answer: yes and no. Overall, the Committee “added tremendous value” to the process, but its structure and authority have “significant weaknesses,” wrote the co-authors, who include Paul Mitchell of the California-based Redistricting Partners and Jordin Tafoya of BSP Research.

And here New Mexico is not alone. In states with advisory commissions, legislators rarely take the advice, more often ignoring or significantly changing the maps they’re given, the study found.

New Mexico lawmakers created their own maps, even if they tried to incorporate input from the CRC maps and tribes.

“Democrats in the House started to meet a few months before the session, and they made their own maps independent from the work the CRC was doing and any input from the wider public,” one anonymous interviewee told the researchers, adding: “Their plan also protected all incumbents and they played ball with Republicans who were also protected in the maps being generated by the Senate.”

Those findings are reinforced by the Princeton Gerrymandering Project’s redistricting report card, which gave the New Mexico state Senate’s new map an A for partisan fairness, but a low C grade for competitiveness.

New Mexico’s next-door neighbor created safeguards against buddymandering after the public demanded independent redistricting. In contrast to New Mexico, Arizona’s independent redistricting commission scraps all existing districts and redraws new ones from scratch every 10 years. And Arizona commissioners are forbidden to consider incumbents’ addresses.

That’s a better way of doing things, said Leonard Gorman, the chair of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission and a member of the New Mexico First Redistricting Task Force. As part of his advocacy for the tribe, Gorman has participated in redistricting in New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, which each include parts of the Navajo Nation.

“Drawing districts around where incumbents live is a disservice to the public,” Gorman said.

But state Senate Majority Whip Linda Lopez, an Albuquerque democrat who shepherded the final Senate map through the legislative process, argued there’s nothing wrong with considering where a sitting lawmaker lives when redistricting.

“The person who has been elected, they’ve already been chosen” by voters in that district, so “we should at least be keeping them in the mix,” said Lopez, who has served since 1997.

Reform advocates tried to persuade legislative leaders to ban consideration of incumbents’ addresses before the 2021 redistricting session, but they refused, Mason said.

Heather Ferguson of Common Cause New Mexico criticized the Senate for claiming its map matched one of the citizens committee maps by 68%, telling the Santa Fe New Mexican: “Well, 68 percent is a D in school, so for them to be proud of what’s essentially a D grade is questionable.”

Increased public participation improved the process

Lopez agreed with the study authors that overall, the process was better this time. “I think it’s improved over what it was 20 years ago, when I first came in,” she said. “There’s more community input.”

By all accounts the Citizens Redistricting Committee engaged far more New Mexicans than the Legislature’s old process, in spite of and perhaps because of the pandemic.

As New Mexico In Depth has reported, only about 100 people attended in the handful of daytime, in-person, non-webcast public meetings the Legislature’s redistricting committee held around the state in 2011.

In contrast, the Committee built a robust website where it posted proposed map concepts, live streamed all of its meetings, allowed remote participation, accepted public comments and hosted Districtr, a user-friendly public map-making tool.

Nearly a third of the 500 “highly likely voters” in the online survey conducted by BSP Research said they participated in the redistricting process this cycle, mostly by looking at maps and information on the Citizens Redistricting Committee website; only 9% went to a meeting in person, largely citing pandemic concerns.

The report praised community organizations including The League of Women Voters, Native Voter Alliance, Common Cause and Fair Districts New Mexico for increasing public participation. In particular, the Center for Civic Policy, a progressive Albuquerque-based community organizing group that had promised to engage under-represented voters in the process, claimed success in turning out nearly 1,000 people to speak at the Committee’s statewide public meetings.

After months of community organizing, the Center submitted to the Committee a “People’s Map” of the state’s three Congressional districts, which they said incorporated Native American groups’ priorities and more fairly represented Hispanic voters. Of hundreds of maps submitted by groups and individual members of the public, the Committee chose the People’s Map as one of only three it submitted to the state Legislature.

But it wasn’t without controversy.

The state Republican Party harshly criticized the Center for offering $50 stipends to offset the gas money or lost wages that could have otherwise prevented them from attending committee meetings. Ethics experts said it would have been wrong to testify for money but that there was no evidence anyone did it just for the cash.

Some committee members said they felt obligated to adopt the map because so many people had worked so hard on it, Mason recalled. He’s worried this could open the door to “astroturfing,” in which it seems as if there’s widespread support for a proposal when, in fact, the perceived support is an illusion created by powerful interests.

“Public input has to be balanced with traditional redistricting principles,” Mason said. A small tweak to the committee’s rules could accomplish that.

The report acknowledged this potential problem, recommending that there should be a clear rule on whether community members may be reimbursed for travel, and that future research should investigate and document the sources of funding for major community outreach efforts.

The Republican party also criticized the Congressional map the Legislature adopted. After Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham signed the maps, the state GOP filed a lawsuit saying the Congressional plan was politically gerrymandered and violated the state constitution.

(In late April a district court judge refused to toss out the map so close to the primary election, but allowed the lawsuit to move forward, saying lawyers for the Republican Party of New Mexico made “a strong, well-developed case” that the plan was politically gerrymandered.)

Reformers will resume pushing for a truly independent commission

The study’s survey shows New Mexicans think more highly of the Committee’s redistricting work than the state Legislature’s. More than 50% had an overall positive opinion of the committee, while only 26% felt that way about state lawmakers.

Fair redistricting advocates such as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU advocate for independent citizen commissions as the best solution to gerrymandering, and more than 75% of the study’s survey respondents said they support further reform and the creation of a truly independent redistricting commission without influence from the Legislature.

Many states have recently moved to various kinds of commission structures for redistricting, and those with advisory committees, like New Mexico’s, are more likely to have politicians discard the commission’s work, Sanchez and Cottrell found.

The study recommended increasing the likelihood that the Legislature adopts the Committee’s maps, perhaps by requiring that adopted maps match the committee’s by at least a certain percentage or that the Legislature choose from among maps drawn by the committee without changing them.

Feedback from survey respondents indicates that any future iteration of a redistricting committee or commission should include much more diverse membership, representing important stakeholder groups, such as Native Americans. The report describes stinging criticism the committee received early on for having no Native American member, and suggests that a future body should consider creating a Native American sub-committee tasked with building consensus among tribes and pueblos.

The cross-partisan New Mexico Redistricting Task Force, which met during the fall of 2020 and issued a list of 18 recommendations for improving the process, continues to assess next steps.

Its No. 1 recommendation in 2020 was establishing a fully independent commission. Mason, who sits on the task force, said he thinks the group will likely resume that fight for the 2023 legislative session.

It’s a goal he and the League of Women Voters, Common Cause and other organizations have sought for decades and there’s no indication state lawmakers are more likely to relinquish this power now.

States where the public is able to propose a law and put it on the ballot—including California, Arizona, Colorado and Michigan—have succeeded in moving to non-political redistricting. But New Mexico does not have a public referendum process.

“If they did, we’d have a commission by now,” Gorman said.

This story was originally published by New Mexico In Depth