In Albuquerque neighborhood, trauma and cyclical family struggles put children at risk

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of stories by Searchlight New Mexico that will explore neighborhoods with some of the worst predictors of child well-being in the state.

BY LESLIE LINTHICUM /RAISING NEW MEXICO — THE ROAD SO FAR/

It’s June and it’s hot and Alexxus Prudhomme’s 17-month-old son, Zymiir, teeters about in a diaper on an apartment balcony, grasping a can of grape soda while his grandmother smokes a joint and argues with the neighbors about the dog mess in the courtyard. “People can’t even sit on their porch in peace without smelling s***!” she shouts.

Her voice travels through the open door to where Alexxus, 17, lies sprawled on the sofa, holding her 5-month-old daughter, Zyhala, and covering her chubby neck in kisses.

Alexxus still wears braces on her teeth, and she misses the carefree social life she might have had if she weren’t stuck in this apartment with two kids. Alexxus got pregnant with Zymiir when she was 15 and a high school freshman.

She’s a dropout now, and home is her mother’s apartment on the second floor of an eight-plex on Wisconsin Street in southeast Albuquerque. The complex consists of two squat buildings separated by a courtyard of dirt and weeds. Concrete sidewalks are cracked and crumbling. The house number is spray painted on the front wall.

Alexxus doesn’t take the kids out much because of the crime and the debris of drug use in the streets around the apartment.

“There’s parks. But there’s a lot of shootings,” she says. “There’s a lot of fighting, drug dealing, needles outside on the floor.”

Alexxus would like her children to know something different.

“I want them around an environment that’s clean, a neighborhood that’s clean,” she says. “I don’t know. I just want them to have the things I never had.”

‘Life vests in the river’

New Mexico is one of the toughest places in the United States to be a child, but within the state there are certain neighborhoods that have the grim distinction of being among the toughest.

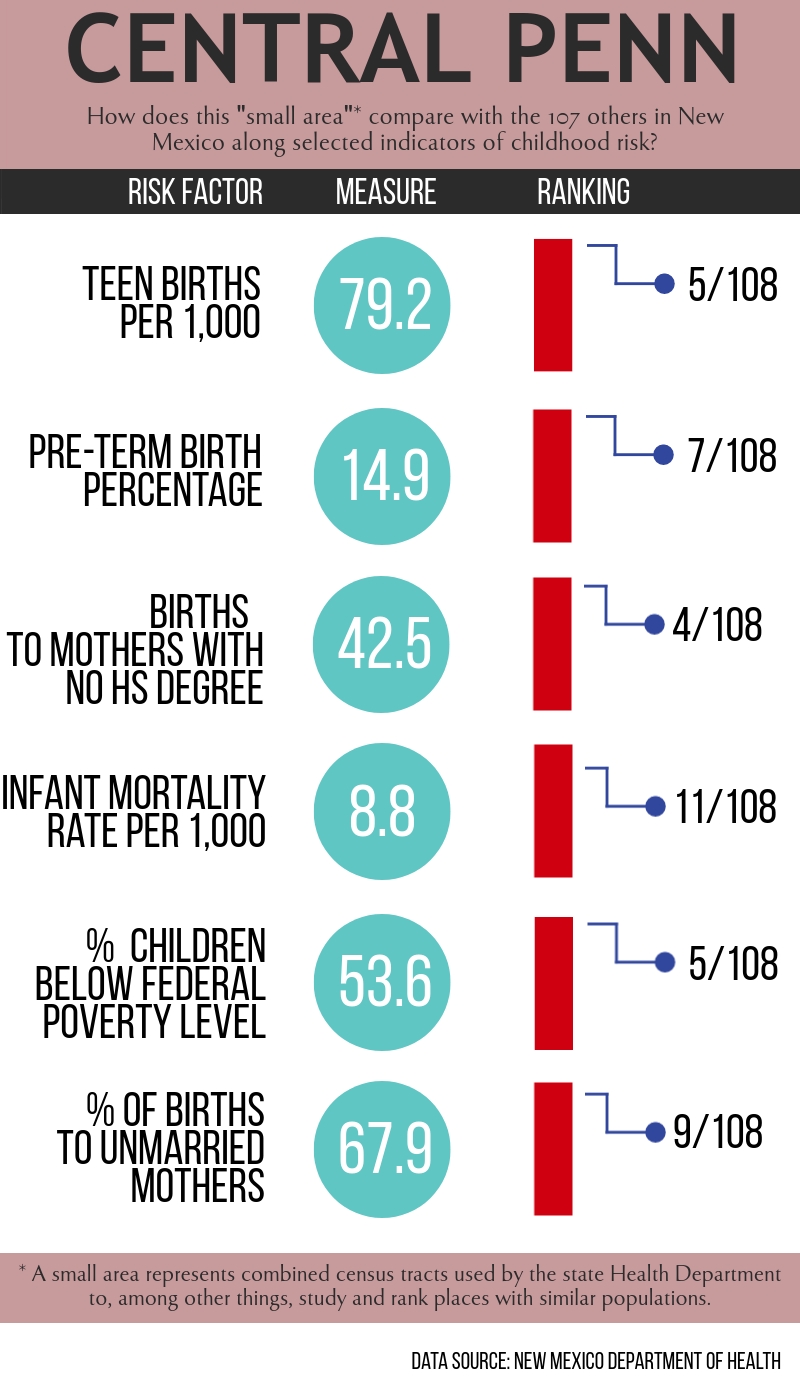

Epidemiologists with the New Mexico Health Department have combined U.S. Census tracts to create 108 “small areas” of roughly the same population size – ranking them according to a dozen risk factors associated with the well-being of young children. Those factors include teen pregnancy, inadequate prenatal care, mothers who are single, mothers who are high school dropouts, family poverty, unemployment, juvenile crime, child abuse and neglect.

The area bounded by San Mateo Boulevard on the west, Wyoming Boulevard on the east, Lomas Boulevard on the north and Kirtland Air Force Base on the south – called “Central Penn” by the Health Department – conforms roughly to the neighborhood known as the International District. While the neighborhood doesn’t rank No. 1 in any single risk factor, it ranks high in almost all, making it statistically the worst in the entire state.

This is the place Alexxus has been raising her children.

And there are a lot of Alexxuses in the neighborhood.

A close look offers a window into the challenges facing children who grow up there. It shows how the trauma they suffer can have life-long impacts and add to a cycle of poverty, neglect, addiction and abuse. It also offers glimmers of hope when those challenges are met with interventions and services – and what happens when they are not.

Health department statistics show about 8 percent of the babies here are born to teenage mothers, 68 percent to unmarried mothers, 43 percent to mothers without a high school degree, and 54 percent into families that are poor.

“We’re the best at being the worst,” says Reynaluz Juarez, who grew up here when it was just a poor neighborhood, before gangs and drug dealers took over the streets in the 1990s and it was nicknamed the War Zone. The neighborhood rechristened itself the International District in 2009, a new name to try to erase the stigma of poverty and crime and to highlight its strengths – an immigrant and refugee population of Asians, Africans and Central Americans that offers vibrant cultural exchanges, dozens of languages and some of the best food in the city.

Juarez works with the International District Healthy Communities Coalition, a Bernalillo County-funded initiative that supports the building blocks of a better community: jobs, nutritious food, safe streets, green spaces where adults and children can exercise and play.

When she was growing up here, kids had to be wary of certain apartment complexes. But they could safely ride their bikes to a friend’s house or walk west to the shady boulevards of Ridgecrest and see how the rich people lived.

The opioid epidemic had not yet taken hold and parks were not littered with needles – yet even then she carried a can of oven cleaner spray (“Mexican Mace,” Juarez calls it) if she was going to be out after dark.

Today, the neighborhood is still mixed ethnically and economically, with trim single-family homes sharing blocks with run-down apartment complexes. Central Avenue runs east and west, dotted with bus stops, restaurants and old motels left behind from Central’s glory days as a portion of iconic Route 66.

The Young Children’s Health Center, run by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, shares a block of San Pablo Street with a family services agency, a WIC office and a city services center that provides food boxes, emergency diaper supplies and help with rent and utility payments.

Clinic medical director Sara Del Campo de González, a pediatrician, treats childhood illnesses while also providing care for adult parents. Guided by an emerging medical consensus, she’s become a firm believer that family life has an enormous effect on children’s health:

“When we’re trained in this trauma-informed model, [it] means we recognize adversity and trauma and how it impacts kids,” she says. “We have our radar set up for it.”

González ticks off a series of questions:

“Is a parent depressed? Is a parent incarcerated? Are they having trouble with transportation? Paying bills?

“A big trauma is deportation or separation from their parent or threat of deportation. These kids are living in constant fear.”

Besides feeling scared or on edge, stressed-out children can show developmental delays, increased infections, behavioral problems, and even stunted growth due to chronically high levels of cortisol, the hormone released in response to stress. Those effects were first documented in the 1997 CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Now regarded as one of the most significant medical reports of the last two decades, the ACE Study looked at 17,000 patients, examined their backgrounds for childhood abuse and neglect, and concluded that cumulative childhood stress increases the risks later in life for heart, liver and autoimmune disease, substance abuse and depression.

So, González says, just offering vaccinations and treating sore throats isn’t enough in a neighborhood like this. Once families enter the sunlit clinic to seek medical care for their children, she surrounds them with offers of help.

The clinic employs a dozen social workers in addition to eight physicians. It provides home visitation, parent support groups, family therapy and a crisis intervention team. Lawyers are on hand once a week to help with immigration cases and landlord disputes. Every Friday, a healthy breakfast is served and parents can sort through a well-stocked clothing bank for their children.

“Trying to have more global impact is really hard from our little place, just trying to keep families afloat,” González says. “We are throwing life vests in the river.”

Going to sleep with gunshots

Outside a low-slung brick apartment building on Palomas Drive, Patricia Aguirre sits with some relatives and her little white poodle. Her husband, Gregorio, a welder, is at work. Her three daughters are inside, right where she likes them.

When Patricia and Gregorio came from the state of Durango, Mexico, to join relatives in Albuquerque in 2004, they landed in this neighborhood.

They have raised their daughters – Clara, 18; America, 15; and Tanya, 11 – in a small apartment, shielded as best they can from the drugs, shootings and gangs outside.

“As soon as you tell someone you’re from this neighborhood they say ‘War Zone’ – that’s how they know it,” says Clara, a senior at Highland High School.

Her guide to the neighborhood? Stay west of Louisiana Boulevard. Avoid The Purple Park (so named because its buildings are painted purple). Don’t worry about the Mexican Park (where Mexican families gather) during the day. “But when the sun goes down, go home.”

She pauses and takes that back. No matter where you are, she says, “as soon as the sun goes down, you go in.”

Children here often go to sleep to the sounds of gunshots and sirens. Clara’s parents have enforced a lot of rules about where the girls can go and how much they study. They fear the influences that lurk outside their apartment walls – as Clara puts it, someone “who could pull you over to the dark side. … My mom was probably the biggest mama bear you could probably find,” she says. “My dad has always been our superhero, always defending us.”

Clara knows her family is poor and worries she is disadvantaged because she didn’t learn English until first grade. She knows the neighborhood schools are poorly rated. Emerson Elementary, Van Buren Middle School and Highland all earn Ds and Fs in the state’s school grade report card.

Highland is one of the poorest high schools in Albuquerque, with 78 percent of its students qualifying for free or reduced-priced lunches. And, like the neighborhood itself, it is diverse – 10 percent Anglo, 73 percent Hispanic, 6 percent Native American and 5 percent black. It has the lowest graduation rate of Albuquerque high schools: just 49 percent.

Yet, Clara is plowing her way through a roster of AP courses: calculus, English, Spanish literature, Spanish language, world history. She is applying to the University of New Mexico and dreams of becoming a pediatric oncologist.

Now that she’s a teenager, Clara has started to question why children in this neighborhood are expected to live with stunted opportunities.

“Why do I have to go to sleep with gunshots?” she asks.

At the same time, she sees strengths in her school and her neighborhood, especially in their racial diversity, and is thankful for the opportunity to learn to navigate and overcome difficulties. She says it has made her stronger.

“Honestly, I wouldn’t change anything that’s happened in the last 17 years for anything,” she says. “I’ve learned from every experience. As tough as people may think this neighborhood is, it’s my home.”

A continuing cycle

Rhonda Ramirez knows these streets better than most. She lived on them for three years, walking the lengths of busy Central Avenue and Zuni Road, up and down the quieter cross streets looking for shelter in alleys and places to score crack, meth and heroin.

When Rhonda first arrived in Albuquerque in 2012, she was trying to escape a life of drinking and drugs in Gallup. She was 30 and had just left behind five kids.

Christiana, 15; Randy, 13; Erica, 11; and Gabriel, 8; were taken in by various relatives on the Navajo reservation and cities nearby. Five-year-old Avelino was adopted by a family in Texas.

In abandoning her children, Rhonda was repeating a family pattern. Fifteen years before, her mother had left her with relatives for weeks or months at a time while she went on drinking binges in Gallup. When she was sober, she was kind, but indifferent, paying more attention to whichever man she was living with than to her daughter.

Rhonda started drinking in middle school, and when her mother found out, she brought Rhonda into a drinking circle of grown men and women who frequented the cheap motels along old Route 66.

When she was 16, an aunt shared some of her second-hand crack smoke, launching Rhonda on a 20-year struggle with heroin and crack addiction.

There were juvenile arrests and time spent in lockups. She dropped out of school in ninth grade and gave birth to five children by five fathers by the time she was 25.

Her life took a series of tragic turns. She was shot in the head in a drive-by while she was pregnant and spent days in a hospital in Albuquerque. Then Gabriel’s father, a crack dealer, was found dead on a street in Gallup, his killing unsolved.

“I was like, ‘Why am I having all of these kids and I can’t even take care of them? And I can’t even take care of myself?’ I was trying to make a change,” she says. “And I couldn’t.”

As she says this, Rhonda is sitting on a comfy leather couch in an apartment on Kathryn Avenue and Palomas Drive in the heart of the International District – or War Zone, as she call it. Her sixth child, a moon-faced 2-year-old named Josiah, is balancing his kiddie chair on an ottoman, looking to his mother for a reaction.

Rhonda is talking about the past, but she prefers to look forward – to raising one of her children for the first time, in sobriety, grounded in a life of church, parenting classes and barbecues.

Meanwhile, Josiah carries many of the risk factors that predict a hard life. His mother was in an unmarried relationship with his father. She never completed high school. She was unemployed. Josiah was born addicted to heroin and methamphetamine. He spent his first year in foster care. His father had a felony record. His mother went to prison for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

A lot of people find God in prison, and so did Rhonda. She also found the Residential Drug and Alcohol Treatment Program, which taught her how to control her cravings and reject the drugs that are so easily available in prison. She learned how to deal with substance-abusing family members and began to attend Native American sweat lodge ceremonies.

Her motivation was to stop feeling ugly inside and to be a mother to Josiah. She repeated a mantra to herself: “I want my son back. I’m going to get my family back together. I want reunification.”

When Rhonda was released from prison after serving 16 months, she went into a re-integration program and began working with the New Mexico Children, Youth and Families Department to regain custody of Josiah.

On May 9, 2017, she returned home to the apartment on Kathryn where Josiah was now living with his father, Frank Lucero, and Lucero’s 9-year-old daughter, Jade. CYFD closed her case. She suddenly had custody of a toddler who didn’t know her.

Josiah screamed and kicked and threw things at her. He pulled her hair. And he refused her attempts to hold him.

She kept trying.

In a matter of weeks, he was cuddling with her and calling her Mom. But he still had a temper that could come out of nowhere.

On a recent afternoon, when Rhonda had been talking too long and not paying him attention, Josiah marched to the refrigerator, picked up a plastic gallon of milk and heaved it across the living room.

He faced his mom, waiting for her reaction. She gave Josiah a look, calmly picked up the intact milk carton and put it back in the fridge.

Rhonda wonders whether her son’s anger is due to his drug exposure or experiences in foster care. She takes parenting classes to learn how to talk to Josiah, how to play with him and how to set expectations without yelling “no!” all the time.

But she’s also hoping to find a behavioral specialist who can help her cope with a son whose emotions can turn on a dime.

“We just comfort him and love him,” she says. “But I think we might need some help.”

‘He didn’t ask to be here’

When Alexxus Prudhomme first became pregnant at age 15, her mother told her to consider her options. She herself had been a teenage mother; she knew the uphill battle her youngest daughter was facing.

Alexxus didn’t want to hear about it. She briefly considered an abortion, but decided to keep her unborn son. “He didn’t ask to be here,” she says. “He didn’t ask for me to open my legs, either. So I can’t really take it out on him.”

Six months following his birth, she got pregnant again. When her second child was born, the infant girl was found to have marijuana in her system and CYFD put Alexxus in a weekly parenting program run by Claudia Benavidez.

With her plume of curly blond hair and wide open smile, Benavidez has been helping parents and children in the International District for the past seven years through the programs she runs for PB&J Family Services across the street from the pediatrics clinic.

Alexxus says the classes taught her “how to be a parent. How to be responsible. How to nurture them. How to talk to them. Discipline. Better ways to do it, basically.”

According to Benavidez, though, it is not that quick or simple.

“Most of our families are lost. They are lost in society,” she says. “The children – you can see it on their face. They have this fighting mode.”

Last summer, Alexxus turned 18, got her driver’s license and found a job at McDonald’s. Things were looking up.

A few months later, she abruptly got her wish to leave the neighborhood she found so dirty and dangerous. But it wasn’t the change she had been hoping for. After a fight with a relative, she and her children moved out of her mother’s apartment and took refuge at a domestic violence shelter in a different part of town.

Alexxus was now on her own.

She was pregnant again.

Leslie Linthicum has covered New Mexico as a reporter and columnist since 1982. She can be contacted at leslie@searchlightnm.com

Editor’s note: This article was first published on Searchlight New Mexico and has been republished with their permission. Minor style changes were made with permission.