By February of 1942, over 110 thousand Japanese people were confined in internment camps throughout the nation, six thousand in New Mexico. Now, a group, New Mexico Japanese American Citizens League, is helping survivors recount their experience in New Mexico’s four WWII internment camps.

The New Mexico Japanese internment camps were located in Santa Fe, Fort Stanton, Lordsburg and the Old Raton Ranch in Lincoln County. The largest, the Santa Fe camp held more than 45 hundred prisoners between March 1942 and April 1946.

Nikki Nojima Louis, a special event coordinator at the New Mexico Japanese American Citizenship League (NMJACL), is a nisei, a second generation Japanese American citizen, born in Seattle, Washington on December 7th, 1937 — exactly four years prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese military. Louis said for her fourth birthday her family threw a party for her at their home in Seattle and that it was in the middle of this party that her life was dramatically changed when just hours following the Pearl Harbor bombing, U.S. government officials came into her home and removed her father, Shoichi Nojima.

Shoichi Nojima emigrated from Tokyo to Seattle, married, had a family and worked as an editor for a newspaper until he was confined at the Santa Fe Japanese Internment camp where he was held until 1946. In December of 1944, U.S. Major General Henry C. Pratt issued Public Proclamation No. 21, which allowed the return of Japanese Americans to their homes on the west coast from Japanese internment camps effective as of January, 1945.

Nojima was first taken to the New Mexican internment camp at Lordsburg which was run by the U.S. army, but then was sent to the Santa Fe camp which was run by the Department of Justice, Louis said. While Nojima was brought to New Mexico, Louis and her mother were sent to a War Relocation Authority (WRA) internment camp in Idaho.

Louis said that Nojima would send her packages while he was in the Santa Fe internment camp.

“I would be sitting on the barrack steps of my camp opening up these packages stamped with N.M. alien mail containing pueblo pottery, beaded jewelry and little wooden dolls. I thought New Mexico was a magical place,” Louis said.

She said that his camp guards, unlike those at other internment camps, were very kind to the inmates and would take them out of the camp and into the town. Her father said the guards would let them go shopping or have free time to themselves but that they had to meet them after a predesignated time so they could all go back to the camp together.

Once Nojima was released he went back to his home and job in Seattle. Louis stayed with her mother and moved to Chicago instead of returning to Washington due to the negative experience that her mom suffered and had associated with her old community. Louis later moved to live with her father in Seattle when she was 16-years-old, when she began to collect his stories. She was with Nojima until he passed away in 1956, when she was 19-years-old.

Durwood Ball, an associate professor of history at the University of New Mexico and editor for the New Mexico Historical Review said that many of the internment camps were located in desolate locations far from towns and cities. Santa Fe’s internment camp was a peculiar exception because it was in the center of town, he said.

Ball said that many of the interned Japanese peoples were that of businessmen, community and religious leaders and were American citizens.

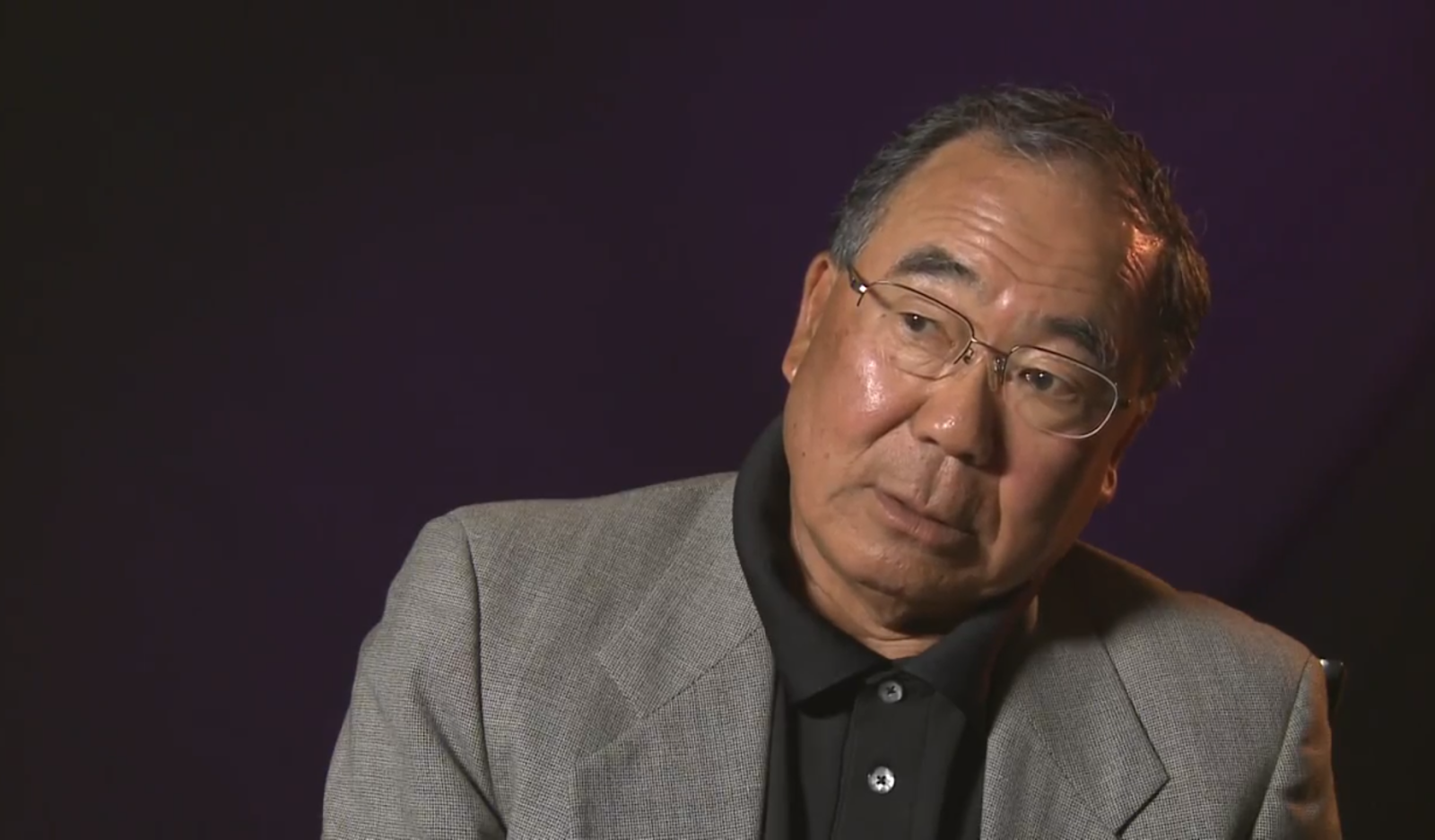

Roy Ebihara, an Old Raton Ranch internment camp survivor, is featured in a 2012 interview with the NMJACL talking about his experience in New Mexico.

Ebihara said that when he was eight-years-old on January 19th, 1942 the local officials in Clovis, New Mexico came to the area of town that he lived in and hastily evacuated all the Japanese peoples offering the premise that a vigilante mob was coming.

“The state patrol came in and said, ‘get going, the vigilante group is forming, they’re coming down through the tunnel and they’re coming out to kill you,” Ebihara said. “They said to grab what you can and throw them in the pillowcase and throw them in the trunk of the car, whatever you can and make sure it’s important valuables.”

Ebihara said it seemed they were in these cars for hours upon hours until they reached Fort Stanton, New Mexico. However, during this time German prisoners of war (POWs) were confined at this camp and it was Ebihara’s older sister that confronted the officials and said their rights as American citizens were being violated by having to be forced into this camp when they haven’t committed any crimes and that the POW men would surely “molest us and kill us”.

After some time passed the officials decided to transfer the Japanese people 17 miles away to the abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp at the Old Raton Ranch, Ebihara said. They all stayed there until the end of 1942 where they were later moved out of the state to the Topaz internment camp in Utah. After his family was released they moved to Cleveland, Ohio and Ebihara has since been an Ohio resident.

Currently, Louis’ group is working with the NMJACL to dramatize the stories that were published in the CLOE report, a collection of interviews and accounts of people interned in New Mexico Japanese internment camps. A highlight article about the NMJACL and a detailed breakdown about the CLOE project can be found here. Louis’ group is planning to travel around the state this coming year to perform their dramatized reenactments of the CLOE stories for New Mexican citizens.

You can follow Marco on Twitter.