By Lindsay Fendtand Annabella Farmer / Searchlight New Mexico

ROSWELL, N.M — Water is the lifeblood of the economy in southeastern New Mexico. It sustains alfalfa fields in Clovis, keeps cows alive on Roswell’s dairy farms and allows for fracking in Carlsbad and Hobbs. Here, the place where water is pumped or diverted is determined more by the exchange of money than the flow of rivers.

All these transactions, many dating back to the early 20th Century, are documented in a small room filled with hand-cranked, moving storage shelves at the District II Office of the State Engineer (OSE). Many of the bulky file folders are torn at the edges or emit a cloud of dust when opened. Some contain hand-drawn maps from the 1940s or copies of typewritten letters from the 1970s, all but translucent with age. In some cases, these are the only records of major water transactions in New Mexico’s 110-year history as a state.

Juan Hernandez, the District II supervisor, laughs when asked about the decrepit filing system.

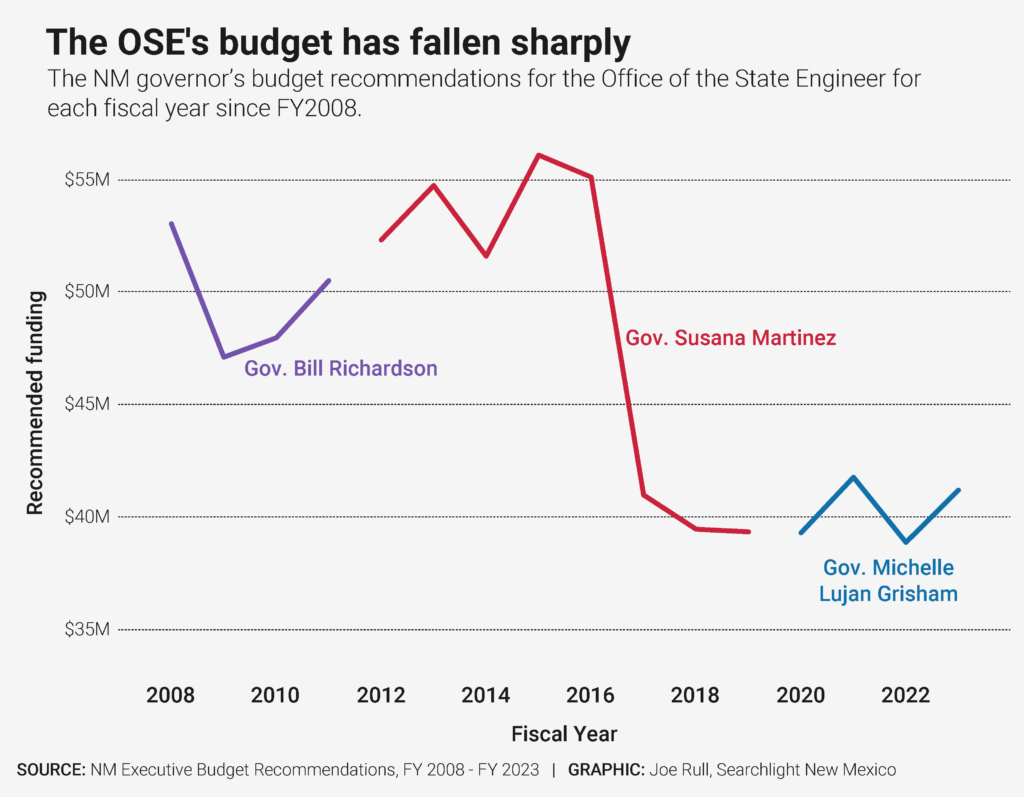

“Are there things we could do better and improve if we had more resources? Absolutely,” he says. But it’s not just the District II office. The OSE as a whole has operated on a 25 percent reduction in its budget since 2017, and it has 67 fewer full-time employees than it did back when Bill Richardson was governor from 2003 to 2011.

The funding issues reached a boiling point in November, when John D’Antonio, the state engineer, resigned his post along with two of the agency’s top lawyers.

D’Antonio’s resignation, effective Jan. 1, left the office leaderless for several weeks, sending the already overburdened agency into a tailspin. Staff were stuck in a holding pattern, unsure if permits issued without an acting state engineer would be valid. But according to the resigning officials, the OSE was already being pushed to its very limits even before their exit.

“We’ve taken the agency as far as we can, given the current agency staffing level and funding resources,” D’Antonio said in a statement after filing his resignation. He declined a request for an interview with Searchlight New Mexico.

There’s no disputing the OSE’s dire need for more funding and staff. Yet a growing number of advocates, water managers and state officials say the department’s decaying paper files and persistent dysfunction are not just a sign of tight budgets, but also a metaphor for an agency and a state water system that have fallen distressingly behind the times.

Confronted with the specter of a New Mexico parched by climate change, some have begun to push back against a water model that focuses primarily on putting as much water to use as possible. Many reformers favor increased funding to water agencies like the OSE, but say the problems go much deeper. They believe it’s time to rethink a system that treats water as a commodity rather than a precious resource.

“We’ve relied on this weird notion that we have an ocean of fresh water in one aquifer or another, and that is inconsistent with what we see,” says Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham. “We now need a whole new situation for a water-policy effort. I think that we need to rewrite what the state engineer’s office looks like.”

The story of the West

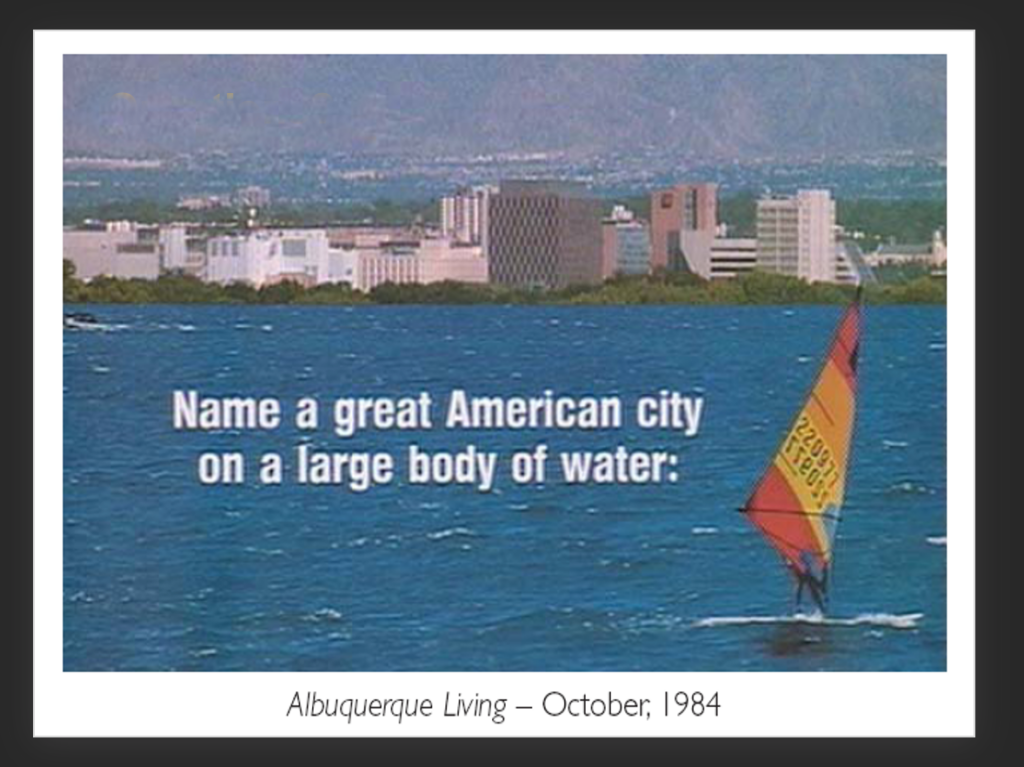

In 1984, a real-estate group published an ad in Albuquerque Living Magazine with an illustration of a windsurfer gliding across a lake, the Albuquerque skyline visible in the background. White text over the image exclaimed: “Name a great American city on a large body of water.”

Rather than a mythical Albuquerque lake, the water in the image was supposed to represent the city’s aquifer, which, at the time, was often portrayed as fathomless. This view was widespread throughout Albuquerque, despite the fact that water managers there were already observing something else: Wells in what had been some of the most productive parts of the aquifer were going dry.

“We knew that the aquifer was not behaving in the way the mental picture was,” says Norm Gaume, who served as the city’s water resource manager during the 90s and later directed the Interstate Stream Commission. “Albuquerque is very well positioned to be resilient in the face of climate change, but development groups in the city were presenting it as a city in the desert with a limitless aquifer, and that was not the case.”

Though repeated droughts and the creeping effects of climate change have tempered the audacious claims of New Mexico’s water abundance, prevailing attitudes are still very much geared toward using as much water as possible.

“It’s really the story of the West,” Gaume says.

Since the late 1800s, western states have taken a largely first come, first served approach to water. Those with early claims on a supply of water are given priority over other users. Often, it doesn’t matter what the water is used for as long as it serves a purpose — a poorly defined policy known in water jargon as “beneficial use.” This system was designed to use every last drop of water at a time when the resource was relatively plentiful. Today, confronted with water scarcity from droughts and climate change, New Mexico’s water governance hasn’t changed much.

“Whatever water is available, we want it to be used beneficially and to go to economic development,” said John Romero, the water-rights division director and acting state engineer. “We want to use it and not hoard it or waste it. That’d be a terrible thing.”

But the current system may not be equipped to deal with a decline in water supplies. The OSE is authorized to issue new permits for water when it determines the water exists and that it won’t harm anyone else’s supply. The agency is not required to analyze how climate change might affect that water right in the future or to balance one type of use over another, like drinking water over agricultural use.

Today, the retired Gaume — now president of Middle Rio Grande Water Advocates — is one of the most vocal proponents of water-governance reform in New Mexico. He and other advocates say the current system is careening down a dangerous path, one that may not leave enough water for river ecosystems, communities or traditional economic activities like agriculture.

Rethinking water

Funding the OSE is the first step toward getting the state’s water future on track, according to Gaume. With that in mind, his organization is seeking sponsors for bills that would increase the OSE’s staff budget by $10 million.

The group is requesting additional funding for infrastructure projects, launching new initiatives and helping New Mexico meet its water obligations to Texas. New Mexico is already facing litigation claiming years of deficient water deliveries, and as water supplies decrease further, costly lawsuits are expected to multiply.

“If New Mexico is to survive its climate-change future, it has to adapt,” says Gaume. “Funding is the first step.”

But many government officials are reluctant to boost recurring funds to that degree. The governor has proposed an increase of $2.3 million, while the Legislative Finance Committee is suggesting an even more modest increase of $979,000.

Other government officials say it’s difficult to justify moving money to an agency that seems geared more towards preserving the current water system than preparing it for a future with less water.

Andrea Romero (D-Santa Fe) is spearheading several water reform initiatives in the 30-day legislative session this month. While she supports funding water initiatives, she’s also expressed some skepticism about forking money over to the OSE.

“We can give you money, but we need to know exactly what it is going to do,” she says. “Are we talking about pushing more water permits or are we talking about conserving water?”

Romero is focusing her actions on water toward reform. She introduced a bill that would change the requirements for the state engineer job. Right now only licensed engineers can hold that position. If passed, the bill will allow hydrologists, geologists, geohydrologists and lawyers to qualify. This shift would fit into a trend throughout the West, changing the priorities of water management instead of focusing on engineering-based solutions. It’s a change that represents a mentality of conservation.

But water reform in New Mexico is an uphill battle. Conservation is still frequently seen as contrary to industry interests. Last year, Andrea Romero sponsored a bill aimed at making the OSE’s operations more transparent (the agency is often criticized as being a ‘black box’), defining “beneficial use,” and requiring the agency to consider climate change when making decisions about water.

She says the bill met opposition from farmers and ranchers, and was eventually assigned to a second committee — effectively killing it.

“I think there’s a huge worry that what reform means is turning the taps off for industry and for future growth,” she says. “It’s easier to just say the status quo works best for big industry.”

Searchlight New Mexico is a non-partisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.