In more than 350 police shootings across New Mexico in the last decade, only two officers were charged with a crime. Why?

by Joshua Bowling/ Searchlight New Mexico

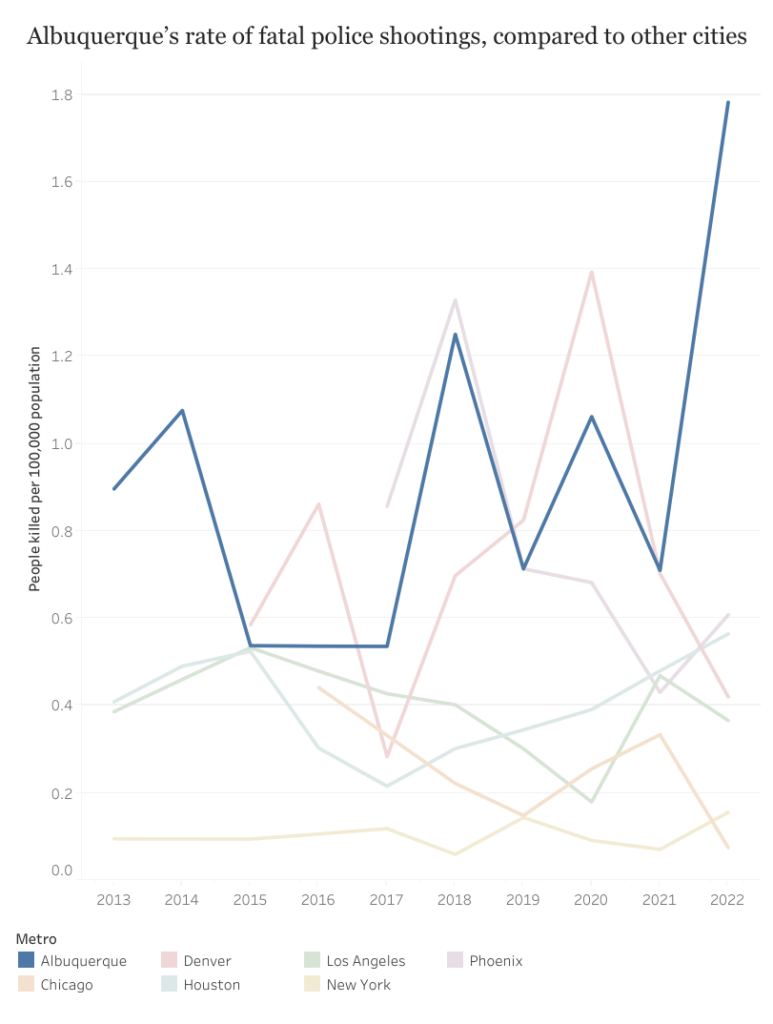

Albuquerque police killed more people last year than nearly any other police department in the country, perpetuating a reputation for excessive force that even the U.S. Department of Justice hasn’t managed to rectify despite a nearly 10-year effort.

In 2022, the city’s police force logged a record 18 shootings — killing 10. That grim number of fatalities was exceeded by only three U.S. cities — Los Angeles, New York and Houston — all of which dwarf Albuquerque in population.

If recent history is any indication, the officers involved will never be tried for the shootings.

In terms of overall shootings, both fatal and non-fatal, law enforcement officers in Albuquerque and surrounding Bernalillo County shot 131 people between 2013 and 2022 — likely a gross undercount, given that the Bernalillo County District Attorney only began tracking this data in 2017.

That number reflects just a fraction of a much larger trend. An analysis by Searchlight New Mexico has identified 226 additional police shootings across the state within that 10-year time period, according to data from 14 district attorneys’ offices. Taken all together, the statewide figure totals 357 shootings, an estimated 211 of them fatal, according to Mapping Police Violence, a nonprofit that tracks data nationwide.

Out of all those shootings, only one has ever resulted in criminal charges. Keith Sandy and Dominique Perez of the Albuquerque Police Department were charged with second-degree murder for the 2014 killing of James Boyd, a homeless man with schizophrenia who was camping in the Sandia foothills. Although the case ended in a mistrial, it played out against a backdrop of increased scrutiny: Less than a month after Boyd’s killing, the Justice Department released a blistering report that accused APD of engaging in a “pattern” of excessive force.

That report set the stage for a decade of federal monitoring under a consent decree. Nevertheless, Albuquerque police have continued to shoot people in record numbers. Last year’s 18 police shootings represented an 80 percent increase over 2021. As of late July, according to a department report, APD officers have shot at eight people this year, killing four.

Foxes guarding the henhouse, critics say

District attorneys rarely, if ever, conduct investigations into these shootings. In some locales, such as Bernalillo County, the DA lets a special prosecutor decide whether to file charges.

For the investigations into the actual incident, district attorneys rely on evidence gathered by outside law enforcement agencies, such as the New Mexico State Police. In some cases, a “Multi-Agency Task Force” composed of several local law enforcement agencies investigates the incident.

Critics and reform advocates say this approach is tantamount to letting the fox guard the henhouse. The investigations are tainted from the start, they say, leaving the door open for law enforcement officials to protect their own.

In theory, a Multi-Agency Task Force is supposed to help avoid conflicts of interest, giving departments that weren’t involved in a police shooting the ability to investigate it. But in practice, critics say, the police department that’s responsible typically plays the starring role: The agency whose officer caused the incident “is the lead agency for that investigation, unless otherwise requested by the appropriate Chief of Police or Sheriff,” as APD’s policy states.

“There are some instances, obviously, where force is justified,” said Laura Schauer Ives, an attorney who has represented the families of people killed in several of Albuquerque’s high-profile police shootings. “But a prosecution is dependent upon a quality investigation. To actually investigate and prosecute cases that deserve prosecution, there needs to be an independent agency.”

Indeed, New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez said he wants the state legislature to fund permanent investigators and prosecutors who can probe police shootings statewide. Torrez, who previously served as the Bernalillo County District Attorney, said the state needs a review process that “eliminates concerns over potential conflicts of interest” while “promoting public confidence in the criminal justice system.”

District attorneys disagree. They contend that the only people who should investigate police shootings are people who understand what it’s like to be a cop.

“I have no problem with the Multi-Agency Task Force. There’s a reason why it’s multi-agency, so that it’s just not APD, for example, investigating APD,” said Sam Bregman, who was appointed in January to be district attorney in Bernalillo County. “Who else is going to do it, right?”

Since being appointed, he’s decided he likes the job and will run for the post when his term is up in 2024. “The hardest job in America is to be a cop,” he said.

Bregman has worked on nearly every side of the issue. In the past, he was a private attorney who successfully represented the families of police shooting victims in wrongful-death lawsuits. He also represented Keith Sandy, one of the two Albuquerque officers charged with murder in the 2014 James Boyd shooting. In that case, after the mistrial was declared, both Sandy and his partner went free.

A deadly U.S. trend

Albuquerque’s record number of police shootings mirrors a national trend: Last year, police across the U.S. killed nearly 1,200 people, according to Mapping Police Violence. That makes 2022 the deadliest year for police shootings since the Los Angeles nonprofit began tracking the data in 2013.

Authorities say that if investigations ultimately favor police, it’s due to the pervasiveness of gun violence since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Albuquerque recorded 120 homicides last year, a 58 percent increase from 2020, when 76 homicides occurred.

That trend changed Mary Carmack-Altwies’ perspective once she became district attorney for the First Judicial District, which includes Santa Fe, Rio Arriba and Los Alamos counties.

After three years as a public defender in Albuquerque, she had big plans to take on New Mexico’s scourge of police shootings. “(But) there’s something going on,” she said. “In my district, it’s that everyone has guns and they’re coming at the police with them.”

Since taking office in 2021, Carmack-Altwies said she has found that officers’ use of force was justified in every case that’s come across her desk. That includes the May 2023 shooting death of John Eames, 77, whom police found holding a gun in a Santa Fe arroyo during a mental health crisis. Santa Fe Police told him they wanted to speak with him, but that he had to drop his weapon first, according to the DA’s report. Eames, who was obscured by bushes, put his hands in the air, both empty, and walked toward the officers. At one point, though, he appeared to reach for his pocket, and police opened fire, killing him.

The report concluded that Sgt. Ryan Alire-Maez and Officer Julian Norris did nothing wrong. “Under the facts and circumstances, all officers acted reasonably in response to an immediate threat to their and their fellow officers’ safety,” it said.

Police shootings rarely lead to charges

Prosecuting a police officer is challenging, but it’s not unheard of. In the last few years, police have been tried for murder in several high-profile cases across the country, including the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. As recently as Sept. 8, a police officer in Philadelphia was charged with murder for fatally shooting 27-year-old Eddie Irizarry, who was killed as he sat in his car.

The Police Integrity Research Group at Bowling Green State University, which tracks criminal charges against police officers, found that between 2005 and 2019, 104 local law enforcement officers across the country had been arrested on suspicion of murder or manslaughter following an on-duty shooting — an average of about seven per year. Of those, 35 were convicted of a crime, it stated in a 2019 report.

In New Mexico, such cases have rarely led to criminal charges — much less a conviction. State law says deadly force is justified if the officer “has probable cause to believe he or another is threatened with serious harm or deadly force” while performing his or her job, a standard that makes prosecution exceedingly difficult.

When the federal government imposed a consent decree on Albuquerque police in 2014, it mandated a series of reforms. A few months ago, the DOJ praised APD for its efforts — equipping every officer with a body-camera and launching a civilian response unit to investigate low-level uses of force — and loosened its grip on the department.

An objective look at the numbers, however, shows that Albuquerque police are firing their weapons more than ever. In the last five and a half years, a single police officer was involved in five fatal shootings. Bryce Willsey, who joined APD in 2015 and currently works in the department’s Criminal Investigations Bureau, has never been charged by the Bernalillo County DA for any of those five fatalities. In each case, a special prosecutor contracted by the DA’s Office concluded either that Willsey was “acting in the line of duty” or that there was not enough evidence to successfully try the case.

In many cases, officials say, police have to make a split-second decision when they fear for their life. “Officers don’t usually choose the situations they find themselves in,” said Michael Cox, a special prosecutor for the DA’s Office who reviewed one of Willsey’s shootings.

Albuquerque Police Officer Bryce Willsey’s string of shootings began with a burglary call (Jan. 7, 2018); followed by a stolen car report (Dec. 23, 2018); a call about a “handgun” that turned out to be a toy airsoft gun (Jan. 6, 2020); a domestic dispute call (April 16, 2021); and a car chase that led to an on-foot pursuit through an arroyo (April 6, 2022).Willsey is currently facing a lawsuit from the family of Juan James Cordova, whom he shot and killed in the 2021 domestic dispute call. The suit alleges that Cordova was “obviously suffering from a mental health crisis” and that “Willsey’s decision to use deadly force…was intentional, reckless and negligent.”

“District Attorneys give the benefit of the doubt to officers,” said Jon Gould, a senior policy adviser in the DOJ during the Obama Administration. An expert on criminal justice reform, he is the current dean of the School of Social Ecology at the University of California, Irvine.

“Juries, up until recently, gave the benefit of the doubt to officers at trials. The badge and the uniform used to mean that there would be a little bit of deference and respect,” Gould said.

When law enforcement agencies investigate a police shooting, deference can seem blatant, critics say. Across much of the state, for example, State Police lead the investigation into a police shooting and forward their findings to the local DA’s office. In the last 10 years, such a case has never led to criminal charges.

Recently, State Police have taken up an investigation into the Farmington officers who on April 5 shot and killed homeowner Robert Dotson. Police, who responded to the wrong address after a late-night domestic violence call, shot and killed Dotson after he opened his front door, armed with a gun.

‘Be very careful‘

In New Mexico’s largest cities, such shootings have increasingly involved acute mental health crises. One of them occurred last April, when Las Cruces Police Officer Jared Cosper responded to a call about an elderly grandmother with dementia.

As the woman’s family greeted Cosper, they urged him to “be very careful” with the 75-year-old Amelia Baca, who spoke only Spanish. As body-camera footage showed, Baca approached the front door, a kitchen knife in each hand. Cosper, who’d been trained in crisis intervention, shouted at her to “drop the fucking knife.” As her family screamed in protest, the officer shot and killed her.

Cosper has been involved in at least one other shooting — a 2021 nonfatal shooting of a man who allegedly pointed a gun at police, according to a review by Searchlight of Las Cruces Police Department records.

The District Attorney’s Office in Doña Ana County has referred the Baca case to the New Mexico Attorney General’s Office, which has yet to decide whether it will bring criminal charges against Cosper.

In 2020, the AG brought charges against another Las Cruces officer — though not for a shooting. Christopher Smelser was brought up on a murder charge for using a controversial restraining technique against Antonio Valenzuela, who later died of suffocation or asphyxiation. A judge ultimately dismissed the charge against the officer. (Bregman, the current DA for Bernalillo County, represented the families of Baca and Valenzuela in civil suits that ended with multi-million-dollar settlements.)

To reform advocates, the few cases that result in charges have come a day late and a dollar short. While the potential for prosecution looms over the Baca shooting, for example, it would be only the second such case to head to a criminal trial out of the hundreds of shootings in the past decade — a fraction of one percent of all police shootings.

“Nobody is that good at their jobs to have that kind of percentage,” said Schauer Ives, the Albuquerque attorney who has represented families of people killed by police. “You have somebody who makes life-or-death decisions, and you don’t want to explore whether those life-or-death decisions are good ones?”

_____________________________________________________________

Joshua Bowling, Searchlight’s criminal justice reporter, spent nearly six years covering local government, the environment and other issues at the Arizona Republic. His accountability reporting exposed unsustainable growth, water scarcity, costly forest management and injustice in a historically Black community that was overrun by industrialization. Raised in the Southwest, he graduated from Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Searchlight New Mexico is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.