A dire scarcity of providers leaves New Mexicans without health care

By Vanessa G. Sánchez/ Searchlight NM

Stacey Dimitt wears many hats. She’s a family doctor, an obstetrician and the chief of staff of Cibola Family Health Center in Grants, a town tucked between Indigenous pueblos and the Navajo Nation.

As an administrator, it’s her job to recruit doctors and health providers to this small rural clinic — one of a handful of medical facilities in the area. It hasn’t been easy. The only family doctor that Dimitt managed to recruit in four years is leaving this month; the other primary care doctor is expected to retire in the next few years. The Cibola Clinic is so understaffed that some patients wait one to three months for an appointment with a family doctor. Dimitt herself is booked until April.

“It’s a real struggle,” she said. “At some point, it would be really hard for a family-practice doctor to commit to coming to us just because of how understaffed we are. It’s clear that the minute you join our practice, you are going to be completely overwhelmed.”

The physician shortage isn’t specific to New Mexico. California, Texas and Florida are predicted to experience the greatest shortages in the country by 2030. But as a predominantly rural state, New Mexico struggles with a unique set of circumstances.

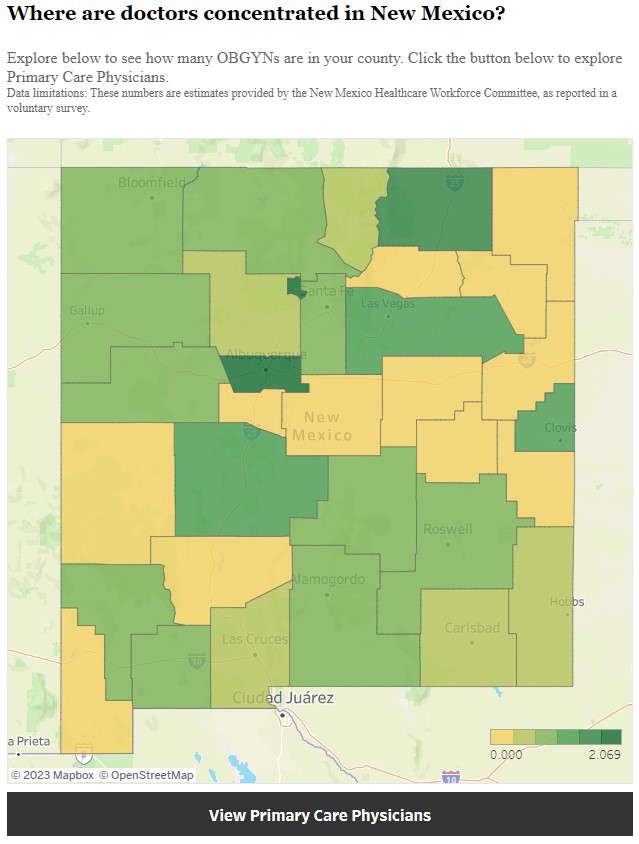

Thirty-two of the state’s 33 counties are designated Health Professional Shortage Areas. As a result, New Mexicans typically wait months to see a doctor, travel out of state to find one or use hospital emergency rooms for non-urgent medical needs.

Nearly 10,000 providers — nurses, doctors, psychologists, specialists — are currently needed to bring the state up to national standards, according to the New Mexico Health Care Workforce Committee, a group of stakeholders from state agencies, the state legislature, health professional licensing boards and other professional organizations.

But the dilemma isn’t just about recruiting new providers. It’s about keeping the ones who are still here. Between 2017 and 2021, the state lost 711 primary care providers, reducing the workforce by 30 percent, according to the Committee’s report last year. The state also effectively lost more OB-GYNs, psychiatrists, registered nurses, certified nurse-midwives, dentists and licensed midwives than it gained in 2021.

Government reports and healthcare advocates point to a host of reasons: a paucity of economic incentives, a high cap on medical malpractice lawsuits and the fact that too few people are being hired from local communities. The aging workforce is another problem: The state’s primary care doctors are approximately 13 years older than the national mean of 40, which suggests there will be additional shortages as they reach retirement age.

“It’s kind of a vicious cycle because you’ve got patients with more health care needs because they aren’t getting in to see a doctor,” said Nick Autio, general counsel of the New Mexico Medical Society (NMMS). “You’ve got doctors who are overworked and that, unfortunately, as a matter of human nature, will lead to worse outcomes, which will feed the medical malpractice issue and higher premiums.”

The consequence is that access to care is drying up. And it should come as no surprise that the population most affected is the nearly 50 percent of New Mexicans on Medicaid. Since the pandemic, an additional 100,000 New Mexicans have enrolled in the program — while access to care has continued to shrink.

Last year, when the Legislative Finance Committee surveyed 500 primary care and behavioral health physicians who accept Medicaid, it found that only 13 percent of calls seeking an appointment ever resulted in one. More than a third of primary care visits exceeded a 30-day wait.

“If that doesn’t get people to open their eyes, I don’t know what will,” said Autio.

The demand has also placed a huge burden on providers. Burnout has shot up, fueling dissatisfaction and turnover at work.

“The pandemic has really taken a toll on our health care provider community,” said Connie Trujillo, a certified nurse midwife at the University of New Mexico Hospital. “Health care providers are leaving the profession in droves.”

Competing for health care

Upon graduating from the University of Kansas School of Medicine in 2011, Dimitt was channeled into a program that expeditiously released her from student debt. That’s because Kansas provides a package of financial assistance — one year of medical school paid off for every year she worked in rural Kansas.

“By the time I moved here,” said Dimitt, “I was loan free.”

Loan repayment programs are a proven strategy to recruit and retain health care professionals, but the one that exists here in New Mexico is not enough to compete with those in neighboring states.

“Texas, Arizona, and Colorado have them, and they are all more generous than ours,” said Annie Jung, executive director of the NMMS. “It’s important to reinforce that we are competing with all of these states for a limited number of doctors, so we have to really encourage and incentivize these doctors to stay here.”

New Mexico’s program equivalent — the Health Professional Loan Repayment Program — caps payments at $25,000 a year, barely enough to make a dent in the cost of a doctor’s education. The average debt a physician takes on to complete medical school is $241,000, according to the NMMS.

To receive this assistance, health care professionals commit to work for two years in a designated Health Professional Shortage Area, many of which are in rural counties and towns across the state. The program’s total funding of $2.8 million is so limited that few individuals even qualify. Last year, for instance, only 60 out of 649 applicants received funds, according to Higher Education Department Secretary Stephanie Rodriguez.

Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) has recommended an increase in funding to $30 million. If the Legislature approves her recommendation, the program will assist in the education of 1,000 health care providers, according to Stephanie J. Montoya, the agency’s public information officer.

High cost of doing business

The problem in New Mexico is multifold, experts say. Health professionals point to the state’s Medical Malpractice Act of 2021 — HB 75, which was intended to modernize a system that had been in place for 45 years.

The bill raised caps on medical malpractice damages from $600,000 to $750,000 for independent providers and from $600,000 to $4 million for hospitals and licensed outpatient healthcare facilities. The latter will increase $500,000 each year until it reaches $6 million in 2026.

By doing so, critics say the state has driven up the cost of liability insurance, creating an inhospitable climate — compared to states like Texas, which caps damages for independent providers at $250,000.

Independent outpatient facilities are finding it difficult to obtain insurance because the cap is so high, according to Jung. (There is pending legislation in New Mexico’s Senate that will, if passed, ease the problem somewhat by leaving the cap at $750,000 for independent outpatient facilities.)

The high costs are yet another reason that Dimitt has found it hard to recruit and hire.

“I have had applicants who have been considering us and then have heard about the high rate of malpractice lawsuits and have opted not to pursue us any further,” said Dimitt.

“General surgery and obstetrics are specialties that have high lawsuit rates just by the nature of what they do,” she said, adding that these specialties are the most needed in her clinic. “Those two specialties in particular are going to pay more attention to malpractice issues.”

Young health professionals said they consider these and other issues when choosing a specialty.

Consider Sarah Putnam, a University of New Mexico (UNM) medical student who expects to graduate in two years.

Putnam, who grew up in Albuquerque, has long known that she wanted to be a doctor. In college, she shadowed a doctor in the Zuni Pueblo where she witnessed the direct impact physicians can make in rural communities. She is interested in pursuing obstetrics or a specialty in maternal and child health.

“I can’t picture myself doing anything else,” she said. “But with that comes a lot of considerations of long-term satisfaction and sustainability with your practice.”

The ongoing battles around reproductive health and abortion access have given her pause. After participating in a Practical Immersion Experience for six weeks with an OB-GYN doctor in Farmington, she saw firsthand the obstacles that maternal health care workers face in rural New Mexico.

Last year, two labor and delivery units closed in two hospitals, and a maternal health clinic – the Women’s Medical Center in Clovis — went out of business. In the last decade, a total of six maternity wards have closed, according to the New Mexico Department of Health.

Putnam is concerned about stepping into the vacuum, citing the fact that when Rehoboth McKinley Christian Hospital in Gallup closed its labor and delivery unit, providers in Farmington — 111 miles away — had to step in to fill the need.

“OB-GYNs in rural New Mexico as a whole are overworked,” said Putnam. “They are being required to work long hours and are on call all the time.”

Need for diverse workforce

To guarantee timely and adequate care, advocates said that New Mexico needs to diversify its health care workforce.

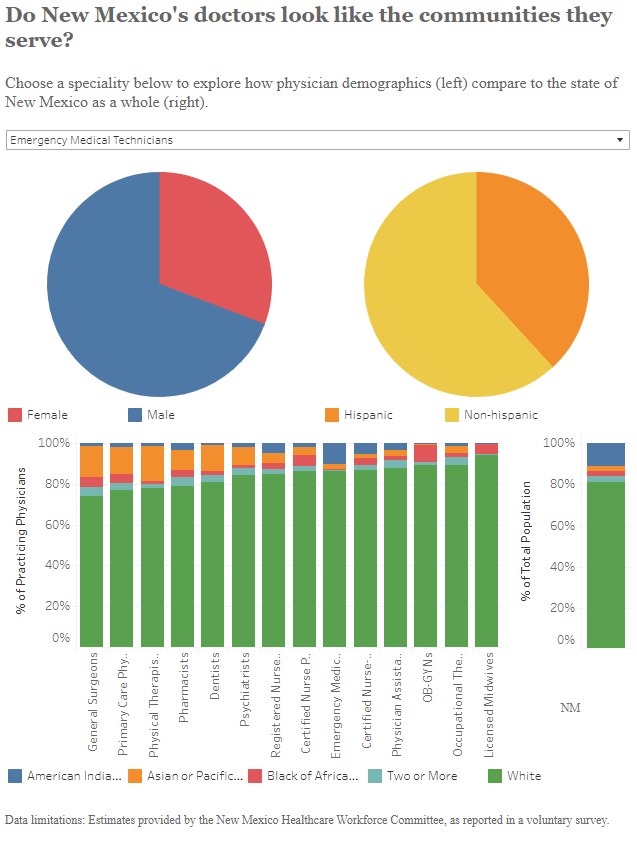

Research repeatedly shows that a diverse workforce can help overcome health care shortages and pave the way for greater health equity. Moreover, physicians from racial and ethnic groups that are traditionally underrepresented in medicine are more likely to remain and practice in underserved communities.

“The shortage is really related to the lack of representation in health care,” said Estela González, a nurse practitioner student who is slated to graduate from UNM in May. “To be able to retain people, you need to retain people of color, you need to recruit them.”

An Indigenous Mexican woman from the Purépecha people, González moved to New Mexico more than a decade ago, largely because the state offered something that Oregon — her home for 22 years — lacked: a diverse community of sovereign nations and pueblos.

What she discovered was that New Mexico itself has a long way to go. While almost half the population identifies as Hispanic or Latino, 75 percent of its clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse practitioners and psychiatrists are non-Hispanic white. Native Americans make up over 11 percent of the population but are represented by less than three percent of primary care doctors, OB-GYNs, dentists, surgeons, nurse practitioners and physical therapists.

“They are the ones that are going to make those communities thrive because they come from those communities. They live there, they work there. They shop there, their families are intertwined with the communities,” González said.

Searchlight New Mexico is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that seeks to empower New Mexicans to demand honest and effective public policy.