By Barbara Ramirez / NM News Port

Dia de los Muertos, or The Day of the Dead, is a Mexican tradition in which the living call on the souls of loved ones who have passed away, welcoming them to a reunion in our earthly plane.

“Dia de los Muertos is a time to remember those who passed,” said Rusita Avila, a long-time community organizer and healer in Albuquerque.

“In the Mexica or Aztec tradition, we have a ceremonia (ceremony) where we call them,” Avila said. “It is very private. You have to be invited.”

Avila was the director and co-director of the South Valley Dia De Los Muertos Marigold Parade from 1999 to 2015. This year the parade was set for Sunday, November 5, at Rio Bravo County Park, next to Harrison Middle School.

Rusita says this tradition runs deep in the culture… and is traced to a mixture of indigenous and catholic celebrations that have been adapted throughout the years.

Historians say the Day of the Dead started around three thousand years ago by the Aztecs and the Toltecs. The belief is that after dying, people would travel to Chicunamictlán, the land of the dead.

Indigenous people consider death an important chapter of life, not the end of life.

The ancient Mexicans knew that the souls of those who passed would come back to visit if they called them during the Dia de Muertos celebration.

“We do that by having an altar where we put pictures of the person and some of the things that they loved in life,” Rusita said. “Art, music, or maybe even drinking alcohol and smoking.”

“It’s symbolic so that the spirits come, and then they get to feast in that way.”

Traditional Day of the Dead altars are set up in rooms, on tables or shelves, with various tiers symbolizing different levels of existence. Typically, two-tiered altars represent heaven and earth, while three-tiered altars incorporate the concept of purgatory.

Some altars have seven levels, symbolizing the steps required to attain heaven and find eternal peace:

Symbolic objects frequently found on Day of the Dead altars:

Deceased’s photo: Placed at the top.

Cross: Introduced by Spanish evangelizers.

Copal and incense: Cleanse and sanctify.

Papel picado: Represents festive joy.

Candles: Guiding lights.

Water: Reflects soul’s purity.

Flowers: Decorate and guide spirits. Marigolds are often used.

Skulls: Symbolize death’s presence.

Food: For the deceased to enjoy.

Bread: Represents the Eucharist, added by Spanish evangelizers.

New Mexico celebrations have roots in the Chicano Movement

Community member and organizer Enrique Cardiel became involved in the South Valley parade and celebration in 1992 as part of La Raza Unida, a Chicano rights group.

Some of his roles in the parade and celebration included sound engineer, face painter, musician, organizer, and committee member.

Cardiel credits Sandra and Jorge Castro, originally from California, for initiating the South Valley Marigold Parade and Celebration in 1991 as part of a move to revitalize and pay tribute to Día de los Muertos traditions.

“We met and we did prayer. It was at the Westside Community Center,” Cardiel said. “We didn’t ask for permission. There were 20 to 30 people; it was not the big event that it is now.”

Avila agrees that the “Muertos y Marigolds” was more an expression of community, not religion.

“The South Valley parade was more focused on the artistic presentation of the culture,” Avila said. “It wasn’t supposed to be a spiritual thing.”

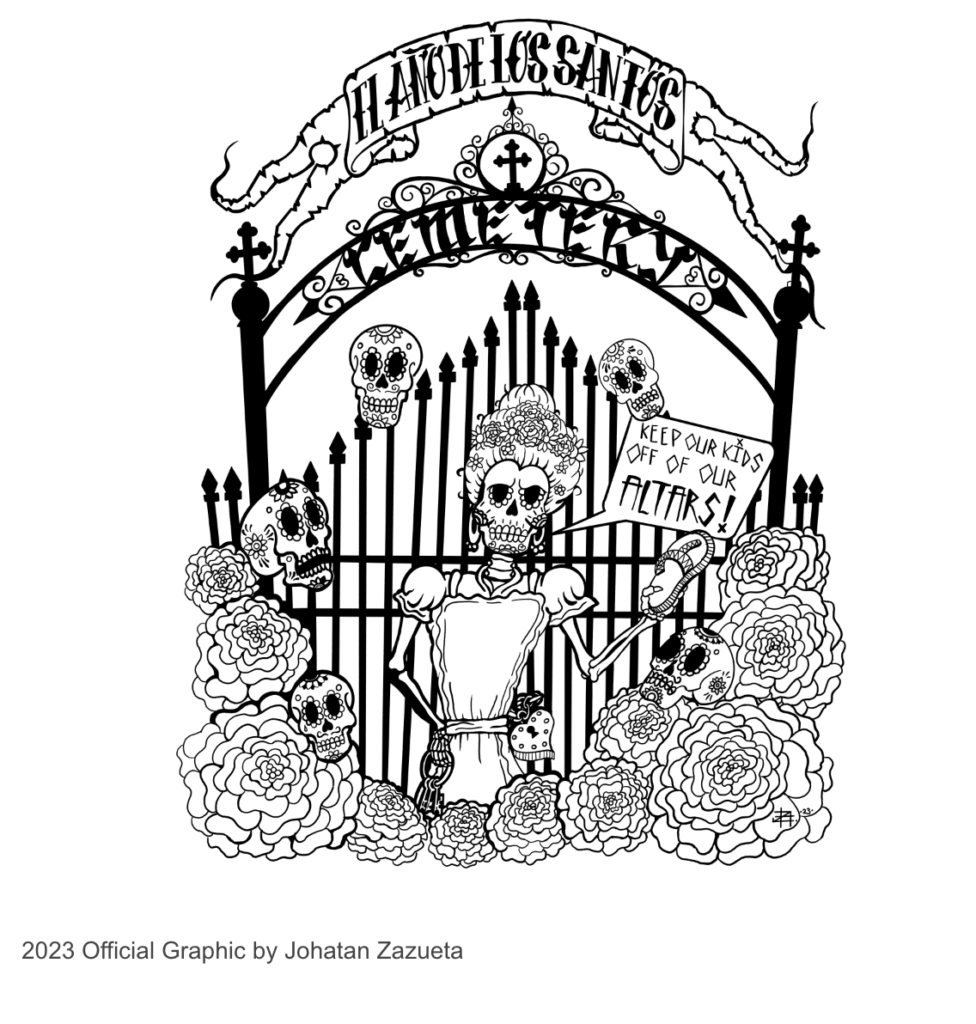

“There has been some pop culture, cultural appropriation that’s happened,” she said. “We were trying to protect the cultural purity of it and the artistic value of Dia de los Muertos.”

Jesus Hernandez and Hector Sanchez are from Chihuahua, Mexico. Sanchez has lived in New Mexico for the past 23 years, and Hernandez has lived here for 15 years. They are in the modeling and fashion show industry. They use their platform to continue their traditions on Dia de Los Muertos and Catrinas.

“In Chihuahua, we go to the graves where our loved ones are, and we clean them, we put flowers, we say a prayer, that’s how I grew up,” Sanchez said.

“The idea was to spend the whole day and live with the deceased. Bring them their favorite dishes, photographs, clothes, and objects that they used,” Hernandez said. “It is also common to pray a rosary and talk about memories of them.”

“José Guadalupe Posadas (Creator of La Catrina) was inspired to commemorate and satirize that many Mexicans denied their origins and wanted to be like Europeans,” Hernandez said, “at that time, the middle class wanted to appear rich.”

Sanchez and Hernandez are working on a fashion show focused on the Mexican character La Catrina as part of EH Modeling Agency. This female skeleton character is very popular during Dia de Los Muertos. Models will have their faces painted and walk wearing traditional Catrina outfits. The fashion show will occur on Friday, November 3rd, at Valle de Luna Event Center.

The Day of the Dead is similar to the Catholic European tradition of All Souls Day and All Saints Day. These began as pagan observances honoring the deceased — including bonfires, festive dances, and indulgent feasts — which the Roman Catholic Church informally incorporated into their feast days observed during the first two days of November.

Because of the colonization of the Americas, some indigenous traditions and catholic traditions are now inextricably mixed.

Barbara Ramirez is a 22-year-old Venezuelan majoring in multimedia journalism and minoring in political science at the University of New Mexico. Barbara and her family moved to Albuquerque in 2016 seeking political asylum.

Follow Barbara on Instagram: ramirez_barbara_01