By Alicia Inez Guzmán / Searchlight New Mexico

LAS CRUCES — It was 3:30 p.m., and a line had already begun to form inside the Karen M. Trujillo Administration Complex, an old strip mall on South Main Street. The school board meeting was still 30 minutes away, but more than a dozen people stood in the building’s atrium awaiting the chance to sign up for a coveted spot in the public comment period.

It was a familiar crowd — community members, advocates, parents, teachers and students — some of the most hopeful and irate voices in Las Cruces. And they were eager to address the latest issue of contention: a gender inclusion policy that called for a safe environment for all students, “regardless of sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression.”

“Children will have to deal with bestiality and extreme homosexuality as a result of this,” Clarice Francis declared at the podium, once the public comment period began.

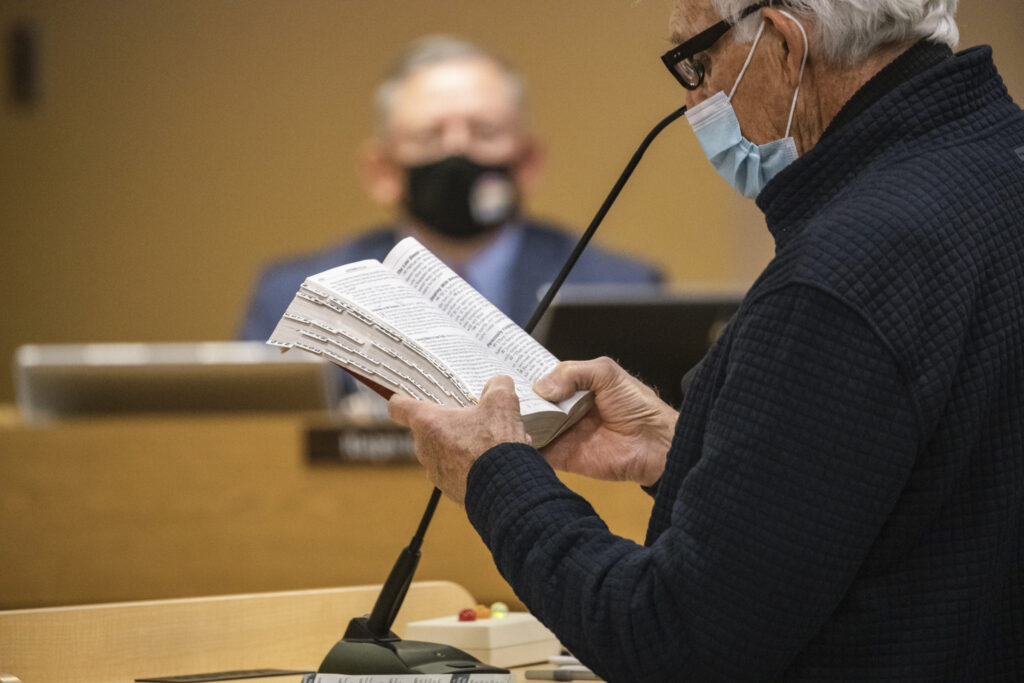

“You know what the right thing to do is — follow this book,” said Charles Wendler, who denounced the policy by reading from the Bible.

“I pray that God will give you the courage to vote his heart,” Lonti Hamilton said, imploring the board to reject the measure. Like the others, she garnered a small wave of applause among the crowd of 80 in the auditorium.

“What we’re asking for,” countered Anastasia Zuniga, 22, “are basic human rights and the rights to a fair, safe place.” Zuniga was one of several young people at the meeting, including high school students, recent graduates and other advocates, who described being bullied by other students or outed by teachers — proof that the policy was necessary, they said. Their speeches garnered their own cheers.

Every Las Cruces Public Schools board meeting since last spring has been both a stage and a battleground, and this one, on Jan. 4, would be no different. Public schools nationwide are reckoning with how American, state and regional histories are taught and what voices are celebrated or silenced. And in Las Cruces, as elsewhere, the school board podium has become a powerful political platform. Conservatives are flocking to the meetings in an effort to assert their views and shape education in their own image. Liberals, they assert, are doing the same.

“This is not about education,” as Elizabeth Ortega, who spoke at the school board meeting, described it. “It is about indoctrination, and we must push back.”

In Las Cruces, that pushback extends to a wide range of issues, whether they’re on the agenda or not. The Jan. 4 meeting, for example, was supposed to focus on the proposed gender-inclusion policy (the measure eventually passed on a 4-1 vote). But in attacking the policy, opponents mentioned everything from guns, God and gender-neutral bathrooms to one of the most hotly contested issues of all: critical race theory.

Rising conservative opposition

Conservative opposition to school board proposals has been mounting in Las Cruces since last spring, when the district passed a sweeping reform entitled Equity and Excellence for all Students, which sought to undo the harms of decades of discrimination and assimilation in the education system.

Amidst the contentions over that and the gender inclusion policy, the state’s Public Education Department released a draft of New Mexico’s social studies standards, crafted in response to the Yazzie-Martinez lawsuit. The landmark ruling in the case established that New Mexico’s education system was so inadequate that it violated the rights of students, including children of color, Native Americans, English-language learners and students with disabilities.

Extensive reforms were ordered in the aftermath, and PED set about updating its social studies standards, releasing a 122-page proposed draft last September — a time when rhetoric about critical race theory (CRT) happened to be at a fever pitch. Resistance was swift.

Over the next 45 days, PED received 2,909 pages of written correspondence about the proposed new standards and 109 verbal comments at an online public hearing on Nov. 12. It was the most feedback the agency had ever gotten, according to Gwen Perea Warniment, PED’s deputy cabinet secretary.

In Las Cruces, the proposed standards dovetailed with other flashpoints like COVID-19 vaccines and mask-wearing, creating a crucible of conservative anger. Political opposition flourished, as did membership in a small nonpartisan citizens’ group, Coalition of Conservatives in Action (CCIA), founded last March.

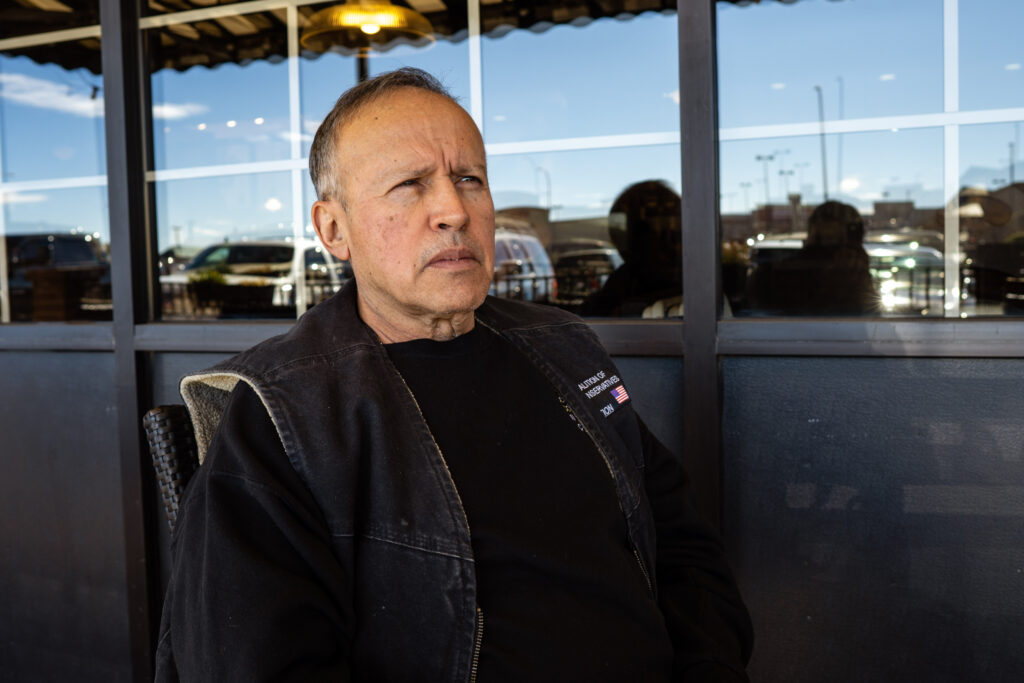

“They’re just trying to find the 87 designer ways to make students into victims,” CCIA member Rick Reynaud said in an interview, referring to school equity measures and the proposed social studies standards. Reynaud has been a vocal dissenter at Las Cruces school board meetings, along with Juan García, the president of CCIA, which now claims some 56 dues-paying members. Both men believe the new standards would teach students “what to think, not how to think.”

Even though none of the standards mention critical race theory, García believes they’re critical race theory just the same.

“Just say what you really mean,” García said of the efforts. “It’s CRT.”

An obsession for Fox News

For a legal definition crafted more than 40 years ago, critical race theory has, over the course of the pandemic, become a trigger phrase in conservative circles. Fox News especially has fixated on CRT, mentioning it nearly 2,000 times in the first half of 2021 alone. The theory, which offers an analysis of how racism is ingrained in legal systems and policies, has morphed into an umbrella term that’s used to attack social justice movements, ban books and prevent schools from presenting accurate U.S. history. School board meetings have become ground zero for the debate about what should be taught — and whose stories are told.

The consequences have been immense. Since 2021, 29 states have taken steps to outlaw discussions of race, racism, gender and more expansive understandings of American history in classrooms, or “educational gag orders” as a PEN America report calls them. New Mexico is among them: On Jan. 19, Republican state Rep. Rebecca Dow, a candidate for governor, introduced House Bill 91, which would “prohibit the teaching of CRT” in New Mexico.

In October, Texas state representative Matt Krause sent a list of 850 books about race and gender to school districts across the state, demanding to know whether they were on library shelves. And televangelist Pat Robertson called CRT a “monstrous evil” that will allow people of color to “get the whip handle” and spark the overtaking of white society.

New Mexico hasn’t been spared the controversy. The proposed social studies standards have been especially contentious, with some critics going so far as to dub them “socialism studies.” When they are adopted, the thinking goes, students will be initiated into Marxism and Communism and taught that “every white person,” in the words of Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), “is a racist.”

New Mexico’s school reforms aren’t without fans. Hundreds of people wrote to PED to praise the new social studies standards, which the agency spent years crafting and tweaking with educators and community members statewide. The focus of the standards, said PED Deputy Secretary Warniment, is on “historical accuracy.” But that hasn’t quelled dissent.

‘Stop racial division’

Last summer, a billboard loomed over the intersection of N. Valley Drive and Tashiro in Las Cruces. “L.C.P. S.: Educate Don’t Indoctrinate. Stop Racial Division,” it proclaimed. A second billboard followed months later, this time with the phrase “Let’s Go Brandon” — code, in Republican circles, for “F**k you Biden.” Both billboards were paid for by Juan García and Rick Reynaud of CCIA.

Members of the group met weekly to discuss topics such as parental rights over vaccinations and mask-wearing. They analyzed district policies with a fine-tooth comb and consistently showed up at school board meetings with prepared statements. They emailed board members regularly and even bought “Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Teaching and Learning,” a book they claimed was referenced by Las Cruces Public Schools and PED, to point out what they believed were CRT-laden tenets.

The group, which had originally been founded for Hispanic conservatives, soon grew to include other locals who were concerned about crime and election integrity, among other issues. And, with the release of the standards in the fall, they were primed to act.

Members of CCIA and other critics argued that the new standards would lead to a “victim mentality” and “indoctrination.” Indoctrination, in this view, means any teaching that challenges America’s greatness, the supremacy of capitalism or the belief that racism ended after the civil rights movement.

It was an argument that crystallized with the help of former President Trump, who defined the view in a 2020 speech.

“We must clear away the twisted web of lies in our schools and classrooms, and teach our children the magnificent truth about our country,” Trump proclaimed at the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C. Teaching children about racial inequities was the same as child abuse, he said. Left-wing indoctrination, he went on, had for decades “warped, distorted, and defiled the American story,” teaching students that the country was built on “oppression, not freedom.” It was a devious attempt, he concluded, at making Americans “lose confidence in who we are, where we came from, and what we believe.”

Arguments against CRT in New Mexico were near carbon copies of this same “national script,” said Glenabah Martinez, an associate professor in the University of New Mexico’s department of Language, Literacy, and Sociocultural Studies and director of the Institute for American Indian Education. There was a particularly brisk trade in the word “indoctrination,” which had been commandeered by the right to snap people into action.

Among those using it was Rebecca Dow. “The current administration seems to be in a huge rush to transform the current standards away from general information sharing and more toward political indoctrination,” Dow told Searchlight New Mexico in an email.

When PED published the draft social studies standards, the Republican Party of New Mexico released a statement calling on people to oppose them, asserting that “government should not be indoctrinating students.” At least 10 school boards around the state circulated a petition to PED asking for more time to “adequately review” the standards.

House Republican Caucus members sent a letter to PED, calling the standards “Marxist-inspired” ideology. House Republican Whip Rod Montoya issued his own letter, blaming progressives for pushing “race wars.” Facebook groups like Unmask Artesia Kids embarked on letter-writing campaigns. The right-wing Piñon Post, whose pro-Trump founder was at the Capitol during the Jan. 6 insurrection, published multiple anti-CRT screeds; so did the conservative think tank Rio Grande Foundation.

In Las Cruces, a group of pastors had already begun meeting with García to establish a faith-based charter school. Lots of parents would disenroll their children from public schools because of the standards, they believed. They wanted to be prepared.

Overhaul ‘long overdue’

The commentary PED received about the new social studies standards was acutely divided. But among the respondents was a cadre of dedicated supporters: parents, students, school boards and community members across the state who believed the standards would reduce inequality and improve critical-thinking skills.

The overhaul was “long overdue,” said Warniment, who noted that standards are revised every 10 to 15 years to keep up with national best practices. “We want our standards to be academically rigorous and prepare students for a career and civic life,” she said, “but also really ground them in their identity.”

For example, PED added a standard entitled “Ethnic, Cultural and Identity Studies,” which asks students to demonstrate a broad understanding of differences in culture, race and identity, imbalances in power and the origins of group privilege. For high schoolers, other additions include coverage of “the experiences and activism of the LGBTQIA+ community … including the AIDS epidemic, social movements, resistance and hate crimes.”

Ongoing dissension or not, the proposed social studies standards are due to be published in February, according to PED. They’re expected to be fully implemented in the 2023-24 school year.

“The achievement gap affecting a disproportionate number of students of color was made by design,” said Dulcinea Lara, an associate professor in the criminal justice department at New Mexico State University and member of a committee that advised PED on how to craft the standards. That is, the inequities mentioned in the Yazzie-Martinez lawsuit didn’t arise recently, but rather date to the beginnings of New Mexico’s education system. “During the period of statehood, the school system was all about assimilation and forced self-abnegation — about really rewarding students for denying their story,” Lara explained.

The new standards are intended to address and change that — they are a roadmap for districts, enabling each to tell stories about their communities that have never before been honored, she said. In Las Cruces, this could mean teaching about the presence of Piro, Manso and Tiwa peoples, who until now, Lara pointed out, “have been completely omitted from textbooks.

“At the heart of it,” Lara said, people who oppose the standards are asking teachers “to send New Mexican youth out into the world with an incomplete toolkit. By protesting the new standards, they’re essentially saying, ‘Yeah, I feel comfortable with that.’”

Sentimental miseducation

Collective myths about how the nation formed have often relied on strategic amnesia. The debates about CRT and education are fundamentally about miseducation and romanticized origin stories, supporters of the new standards and other reforms say.

“Indigenous people have been miseducated since the Carlisle Indian School, where they were taught how to be laborers,” said Glenabah Martinez, who is Diné and from Taos Pueblo. “Those who have chosen not to understand marginalized peoples, who do not want to see their own shortcomings — they are also miseducated.”

On Nov. 12, the deadline for the social studies standards public comment period, the Republican Party of New Mexico hosted a rally in front of PED headquarters in Santa Fe. Secretary of state candidate Audrey Trujillo, a speaker that day, held a sign stating, “Segregation is back baby” above the outline of a Ku Klux Klan silhouette, echoing the sentiments of Ted Cruz, who proclaimed that “CRT is every bit as racist as the Klansmen in white sheets.”

Other speakers also co-opted civil rights history to justify their position, saying that Martin Luther King Jr. would be ashamed of CRT.

But the current obsession with CRT points to a sense of growing anxiety over who and what might threaten a national story once believed to be sacrosanct — a story that elevated the experiences of some people and erased the experiences of others. “What’s given CRT so much power,” Martinez said, “is fear.”

Alicia Inez Guzmán

Raised in the northern New Mexican village of Truchas, Alicia Inez Guzmán has written about histories of place, identity, and land use in New Mexico. She brings this knowledge to her current role as education reporter at Searchlight, where she focuses on the lived experiences of New Mexico’s students and the role that equity and cultural literacy should play in the classroom and educational policymaking. The former senior editor of New Mexico Magazine, Alicia holds a Ph.D. in Visual and Cultural Studies from the University of Rochester in New York.

Searchlight New Mexico is a non-partisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.