New Mexico paid millions to a Utah company to text, email and phone “disengaged” students. Was it the right call?

By Alicia Inez Guzmán / Searchlight New Mexico

Illustration by Kevin Beaty / Searchlight New Mexico

In Spring 2020, uncertainty quickly turned to desperation for New Mexico’s Public Education Department. In the first months of the pandemic, tens of thousands of students — as many as one in five across the state — were failing a class, skipping school or nowhere to be found.

In response, the state agency made a rushed and questionable decision: It hired a Utah company called Graduation Alliance to pilot an untested “re-engagement” and academic coaching program that relied on phone calls, emails and texts to help at-risk students.

For its outreach efforts — which critics likened to spam or robocalls — the Salt Lake City-based firm will earn $4.6 million.

What remains unclear is whether the program was worthwhile. Graduation Alliance, purchased last year by private-equity giant KKR & Co. — one of the world’s top global investment firms — did not provide detailed information about what its coaching entailed or offer meaningful proof of the re-engagement program’s effectiveness. A review of company reports and 748 pages of public records revealed no verifiable evidence that it helped students improve their attendance, get better grades, graduate on time or otherwise make academic progress.

To its most vocal critics, Graduation Alliance epitomized a trend at PED of outsourcing sensitive services to out-of-state companies. The agency’s lack of in-house staff to implement needed programs, as one legislative analyst put it, has resulted in a troubling pattern of seeking expertise and skills outside the department.

Hiring Graduation Alliance wasn’t even logical, as some observers said. How, they puzzled, could a Utah call center bring some of the most at-risk students back into the education fold? And why was a private company being paid to replicate services that local school employees were already providing? Teachers and school staff had been sending early-morning text messages, calling and emailing family members — even showing up on doorsteps to drop off supplies and food — ever since COVID-19 arrived.

“Why wasn’t I paid more to do the same thing?” said one northern New Mexico teacher who, like others, asked for anonymity because she feared job repercussions.

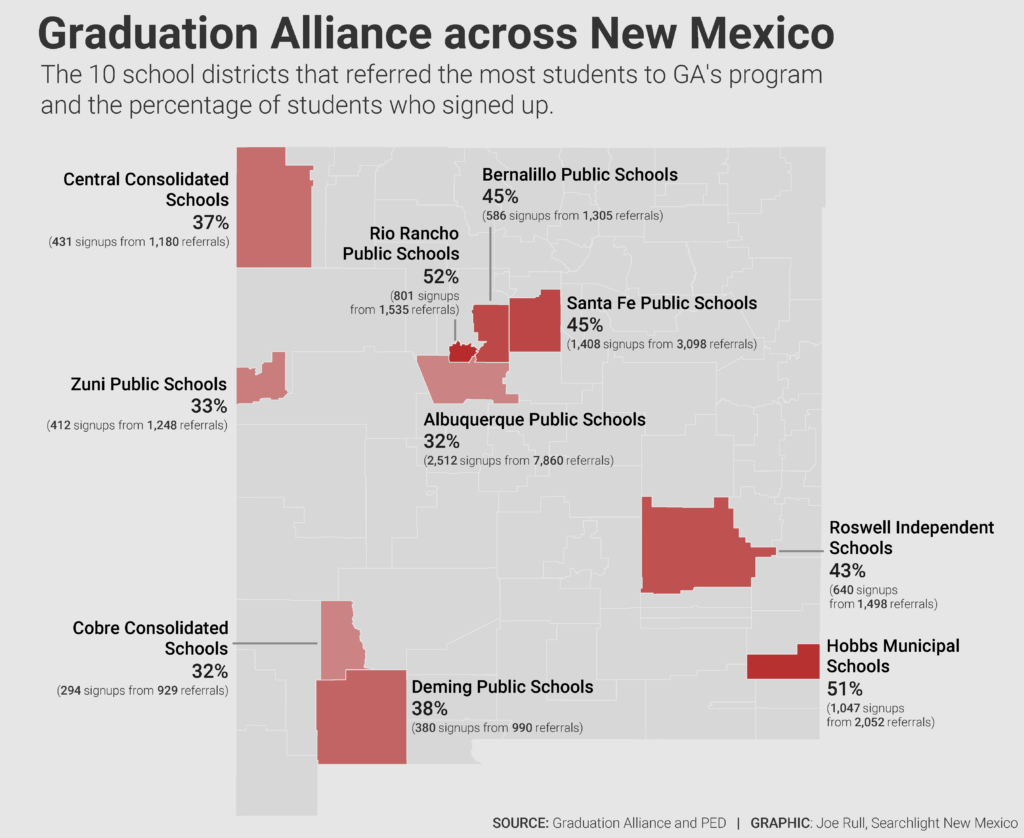

From April 2020 through June 2021, public schools entrusted Graduation Alliance with the names of 45,944 vulnerable schoolchildren, including students who needed help with online learning, were at risk of dropping out or failing — or had fallen off attendance rolls completely. An estimated 17,494 of those students, or 38 percent, eventually signed up for the free and voluntary academic coaching, according to the company and PED.

The program was a great success, according to data in Graduation Alliance’s July 1 final report. The company backed up this conclusion with the results of a participants’ survey: A whopping 91 percent of all parents, 100 percent of Spanish-speaking parents, 96 percent of school districts and 92 percent of 6th-to-12th graders thought the program “maintained or increased” students’ engagement during the 2020-21 school year, the report stated.

The report did not, however, disclose that less than 3 percent of participating students and parents took the survey — a sample so small that it’s impossible to conclude success.

“I fear this is the norm among education vendors,” Todd Rogers, a professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, wrote in an email. Rogers, a school absenteeism expert, said education companies often misrepresent the success of their programs based on anecdotal evidence instead of rigorous testing. “It’s particularly offensive and immoral since the stakes for kids are so high.”

Searchlight New Mexico contacted 20 school districts and canvassed educators from 15 public and charter schools around the state to assess the value of Graduation Alliance’s program, officially dubbed ENGAGE New Mexico. A few educators voiced approval: They said it added an important layer of support for struggling students and families during the chaos and isolation of the pandemic. The majority — especially harried teachers — had never heard of it.

‘Hemorrhaging attendance’

Cobre Consolidated Schools, located in the small southwestern mining town of Bayard, knew it well: The district referred almost the entirety of the student body — 929 students — to the re-engagement program last fall.

“It seemed like in the first quarter of the school year we were hemorrhaging attendance,” said Tony Sosa, the district’s attendance success coach.

The task in Cobre and elsewhere was Sisyphean: find vulnerable children who were by default some of the most difficult to track — and who often lived in homes without broadband and cell-phone service — and somehow draw them into online classrooms. This included students who were “completely disengaged or chronically absent in the virtual learning environment,” a Graduation Alliance report noted, as well as children who were in foster care, lacked stable housing or faced other crises.

Cobre made one big batch of referrals in the fall but stopped once the district was able to address attendance issues and make digital devices available to students. About a third of its referred students ended up participating in the program.

Graduation Alliance provided schools with weekly spreadsheets detailing the number of its contacts with students, which Sosa believed were helpful. But ultimately, he was uncertain whether the program affected academic performance or had an impact on attendance.

“I would check my individual spreadsheets to see if the student was progressing on our end, and it didn’t always translate. Graduation Alliance would say, ‘Yeah we’re really working well with this family,’ but we didn’t always see the benefit of it on our end.”

The service was nevertheless attractive, not only because it was free but also because school officials were trying everything in their power to help struggling families and, perhaps most critically, find errant students.

By November 2020, PED had discovered that approximately 12,000 students had vanished completely from attendance counts. Some of the children had dropped out, left the state, transferred, were incarcerated or even, in a very few cases, had died.

PED launched a major multi-agency effort to locate the students and turned to Graduation Alliance for added help. The company had been in the “drop-out recovery” business for more than a decade; it had some 200 employees at its disposal.

“We worked very quickly together to bring those resources to bear,” said Rebekah Richards, Graduation Alliance’s co-founder and chief academic officer.

The company did what school districts couldn’t do with their own thinly stretched personnel: reach students in high volume, said Katarina Sandoval, PED’s deputy cabinet secretary of academic engagement and student success. The coaching helped create structure and routine — aspects of a kid’s day-to-day school life that were “gone in the blink of an eye” when life went remote.

Blurred lines

Graduation Alliance’s benefits to students might not have been obvious. But the benefits to the company were indisputable. With considerable speed, it essentially became an arm of PED. As such, it was given access to private information about tens of thousands of students, but without the same level of transparency that state agencies must provide.

Emails also reveal the company’s remarkable clout with cabinet-level officials. It won its first no-bid contract with the state (awarded on an emergency basis) in late April, just nine working days after submitting a proposal for the re-engagement program, emails show.

In June, Graduation Alliance released a white paper co-authored by two top officials, lauding the nascent services they said they’d co-created. PED’s Sandoval and Gwen Perea Warniment, deputy secretary of teaching, learning and assessment, joined with Richards of Graduation Alliance to launch what the white paper called a first-in-the-nation collaboration — one that would foster resiliency in students and help them build learning strategies during the global health emergency.

In the coming months, Graduation Alliance was able to use this same white paper to sell its engagement program to Arkansas, Michigan, South Carolina, Arizona and Ohio. The company won at least $9 million in contracts in the process.

The program was a success in New Mexico, even if only 40 percent of students signed up for it, Sandoval said.

“We absolutely think that if it’s 40 percent or if it had been half or a quarter [percent],” it would still be a success, she said. “Every support that we could possibly provide to our students so that they did not become part of the 12,000 unaccounted for [students], is a success.”

It’s possible that Graduation Alliance helped hundreds or even thousands of students. But there’s no way to tell, because the company didn’t measure outcomes. Its reports provide lots of numbers, but the numbers say nothing of the quality, length or benefits of the academic coaching.

Among the numbers: Graduation Alliance employees — scores of them out of state and four in New Mexico — made more than 563,611 “interventions,” as the contacts were called. Academic coaches, who might or might not have credentials in teaching or counseling, made an average of 35 interventions per student, reports said.

Additional numbers come from Graduation Alliance press releases. Founded in 2007, the company has specialized in dropout recovery programs for low-income and disadvantaged students, according to company investors. In recent years, it helped 4,000 students nationwide graduate from high school, its brochures say.

In early 2021, it earned a certification as a B Corporation, a label given to companies that uphold high standards of accountability.

But the company has its controversies, too. Erin Luper, its vice president of government relations and public affairs, is a former lobbyist for the NRA. Luper is credited with defeating gun safety legislation in Tennessee during a string of tragic child shooting deaths and mass shootings at schools around the country. She was instrumental in blocking a high-profile gun safety bill called MaKayla’s Law, introduced after an 8-year-old girl was accidentally shot and killed by an 11-year-old neighbor. When asked why New Mexico would work with a company that employed a former NRA lobbyist, outgoing PED Cabinet Secretary Ryan Stewart said he’d never heard of Luper. Nevertheless, emails obtained through a public records request show that she was included in company correspondence with PED officials.

Graduation Alliance’s methods, meanwhile, borrow heavily from Wall Street, with its New Mexico contract calling for PED to pay per “tranches” of student referrals, a term more commonly associated with mortgage-backed securities than schoolchildren.

The firm’s risk-and-reward logic stems directly from the investment world of subprime loans: For every student in the tranche who got an academic coach, more than one did not because they were unreachable or chose not to participate. PED nonetheless paid for both. In all, the state paid for 28,450 students whom Graduation Alliance never reached or who rejected the service, company data show.

Looking for evidence

Harvard professor Todd Rogers has an unpaid position as cofounder, equity holder and chief scientist at EveryDay Labs, a California-based company that partners with school districts to reduce student absenteeism. He says improving attendance is a long game: Getting students to go to school takes time. The pandemic, unfortunately, demanded swift action.

To see what did and didn’t work during the switch to remote learning, EveryDay conducted more than a dozen large randomized tests, in keeping with the federal guidelines of the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act, or ESSA. The broad aim is to produce evidence-based programs backed by rigorous testing so that “everyone gets better at serving kids,” he said.

New Mexico has its own version of ESSA — a plan called New Mexico Rising — which similarly calls for evidence-based programs. “This should be the norm,” Rogers said in an email. Companies that sell education products should “use theory and evidence to develop interventions.”

Graduation Alliance did not conduct randomized trials to test its services. There was no time to do so, the company said, and PED wanted to act fast.

Nearly every education agency around the country has been looking for a silver bullet during the pandemic, making urgent solutions akin to currency. History shows that the need for such solutions only grows more intense after disasters. Opportunities for making profits also grow. In the wake of the coronavirus, which forced more than 1 billion students worldwide to pursue classes online, the U.S. ed-tech sector attracted a staggering $2.2 billion in private investments — its biggest gains ever.

Back at Cobre, Tony Sosa walked away wondering who saw the greatest benefit from ENGAGE New Mexico — students or the Utah-based company. “Were they working in the interest of Cobre Schools,” he wondered, “or Graduation Alliance?”

Searchlight New Mexico is a non-partisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting in New Mexico.